Having visited the Batatotalena cave temple (featured in the Sunday Observer last week), my next visit was to nearby Batadombalena, home of the ‘Balangoda Man’ named Homo sapiens balangodensis (Balangoda Manawaya) as he is popularly known. It is located four kilometres away from the Kuruwita town in the village of Waladura which can be reached by travelling on the same route that takes you to the Batatotalena cave temple.

Having visited the Batatotalena cave temple (featured in the Sunday Observer last week), my next visit was to nearby Batadombalena, home of the ‘Balangoda Man’ named Homo sapiens balangodensis (Balangoda Manawaya) as he is popularly known. It is located four kilometres away from the Kuruwita town in the village of Waladura which can be reached by travelling on the same route that takes you to the Batatotalena cave temple.

It is more strenuous than the 30 minute climb to the Batatotalena cave temple and it is necessary to trek a kilometre and half through the rainforest, along a steep jungle track that is often nothing more than a jumbled rock or narrow stream bed. It takes you to the Batadombalena cave after a hectic hike – I almost forgot to mention the leeches that clung onto the lower part of the legs. The footpath leading to the summit winds through a small rubber plantation, then a tea estate and a robust full-grown jungle, to rock patches without any support railings and finally, to the historic Batadombalena cave.

The Batadombalena cave belongs to the stone-age, an ageless, timeless period called prehistory, the time before the dawn of history. The Balangoda Man is believed to have lived almost everywhere. However, the richest evidence is found in caves. It is only then that the stone-age begins to take shape in the archaeologist’s mind. Later on, they launched excavations to find the clues about early men who had lived in caves such as the Fa Hsien cave near Bulathsinhala, Beli-lena cave near Kitulgala and Batadombalena cave in Kuruwita.

The Batadombalena cave belongs to the stone-age, an ageless, timeless period called prehistory, the time before the dawn of history. The Balangoda Man is believed to have lived almost everywhere. However, the richest evidence is found in caves. It is only then that the stone-age begins to take shape in the archaeologist’s mind. Later on, they launched excavations to find the clues about early men who had lived in caves such as the Fa Hsien cave near Bulathsinhala, Beli-lena cave near Kitulgala and Batadombalena cave in Kuruwita.

Although the stone-age is lost to us, at Batadombalena it is possible to get a sense of the past. A part of the surrounding areas of the Batadombalena has been declared an archaeological reserve. It is an environment which has not changed for 30,000 years. The dense evergreen foliage is hemmed in by towering trees and the air is damp and humid.

Although it is completely still, it is also full of sounds, the chirping of crickets, the call of birds and the murmur of running water. This was the world in which the prehistoric man lived.

Anyone who has witnessed the verdant lush green Sinharaja forest would know the feeling. Just the thought of laying eyes on that brilliant shade of green, found outside the confines of concrete jungles; the feeling of raindrops on your skin, strangely rejuvenating your being; and the sight of innumerable small waterfalls and streams snaking their way through the rocky outcrops and flowing down the wilderness is enough to soothe one’s nerves.

Leech-infested jungle

The road is motorable up to four kilometres and the rest is a jungle path leading to the cave at a summit that rises roughly 260 m. The trek to the summit is both, long and adventurous. It is a steep footpath that runs through a leech-infested jungle, with a canopy of trees providing cool shade. Armed with my camera and umbrella I set out to the Batadombalena forest reserve with my son.

Before starting the hike, we applied soap on our lower legs to keep the leeches away as it is widely regarded by the locals as the best repellent for leeches. We started our hike from the village of Waladura at the foot of the Batadombalena, the charming hamlet, home to about 500 inhabitants who tend to their small tea lands. A few villagers operate roadside boutiques that sell beverages and food to visitors.

We could hear a strange buzz. It was not an insect. It wasn’t even that irritating high altitude feeling. It was a calm that we had never experienced before. It was the constant rumble of the numerous small waterfalls and streams that dot the area. It is only during the rainy season that these wonders come alive, forming little streams that wind through the trees and creepers found all over the jungle.

After a one-and-a-half hour climb, we reached the Batadombalena cave, which rose majestically through the greenery. I imagined life at the cave 30,000 years ago as we sat on the base of an excavation pit dug by the Department of Archaeology to unearth the skeleton of an early inhabitant in this cave in the latter part of 1981.

The Batadombalena mountain range is an intrinsic part of prehistoric Sri Lanka. The Balangoda Man’s cave is in fact three caves, the largest with a mouth 18m wide and 15 m high. In the middle of the main cave is a large archaeological excavation pit close to the cave mouth. The most significant feature is that archaeological excavations have revealed that the area had seen human habitation 30,000 years ago.

The floor of the cave is covered with shells of tree snails that had been a part of the diet of the Balangoda Man. In front of the cave stood a small clump of wild banana trees (Ati Kehel). Perhaps, the earliest occupants of the cave have eaten these bananas. I have seen similar bananas below the Fa Hsien cave in Bulathsinhala.

The floor of the cave is covered with shells of tree snails that had been a part of the diet of the Balangoda Man. In front of the cave stood a small clump of wild banana trees (Ati Kehel). Perhaps, the earliest occupants of the cave have eaten these bananas. I have seen similar bananas below the Fa Hsien cave in Bulathsinhala.

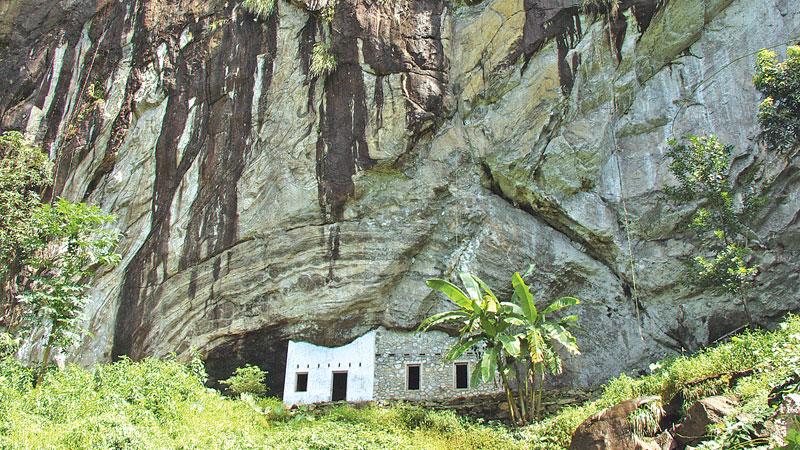

However, in 1969, the cave was used as a Buddhist hermitage by a monastic Bhikku who converted a smaller cave named ‘Ananda Lena’ into an ascetic dwelling by enclosing the mouth with a stone wall with two doors and three windows. What remains inside this cave today, is only a decayed cement bed and a meditating platform made of clay. A beautiful but discoloured Buddha statue still stands in a small shrine built into the cave along with this abode when the hermitage was in use.

Even though the Batadombalena cave itself is small, the rock boulder is massive. Towering overhead, it rises before us like a huge wall. A high waterfall cascaded from the peak of the rock like a long white bridal veil. From far above, the water trickles down, dripping in tiny drops along the blackened stone. During the rainy season, the stream rushes down the mountainside.

Skeleton

Among the discoveries were human and animal remains and various implements as well as large quantities of worked and unworked stones believed to have been used by the ‘Balangoda Man’. The skeleton which was uncovered at Batadombalena around 1980 gives us some idea of what an early man might have looked like. It is through these clues that we must piece together our picture of the prehistoric man.

It appears that both, the male and female were on average taller than they are today, the men, five feet eight inches tall and the women around five feet five. The ‘Balangoda Man’, had strong bones and a thick skull. His jaws were heavy and his teeth very large. Although his neck was very short, his chin was sharply pointed and his nose, wide and flat.

Many of these early inhabitants live on through the Adiwasi (Veddha) community today and it is widely supposed that the people of the Stone Age resembled the Adiwasis closely. Like in the early Adiwasi community, hunting was part of their daily lives. Clad in bark or animal skin, they would hunt and trap animals whose remains they carried back to their cave shelters.

Everyone who visits this forest reserve must protect its pristine beauty for future posterity. An unpleasant sight in this pleasant environs is the rapid deforestation in and around the forest reserve.

Villagers living along the mountain slope have cleaned the jungle to make way for tea and rubber cultivation. The cultivations are a great threat to the fauna and flora of the Batadombalena forest reserve. It is imperative that the forest rangers take urgent action to halt the deforestation that would result in the desecration of an ancient historic treasure.

Although the cave is deserted today, even 500 people could, at a time, find shelter in the Batadombalena cave, which comprises a cluster of small caves. It is a rock that stands testimony to one of the world’s oldest human civilizations.