‘Enchantment galore’ upon the senses of theatregoers seemed the motive and motif for the twelfth year anniversary show of ‘Pyramus and Thisby’ written and directed by seasoned theatre practitioner Jehan Aloysius, which unfolded on the boards of the Wendt on July7.

From the very outset it was clear that this was a labour of great passion displaying skill and planning on the part of the theatre company, Centre Stage Productions headed by Aloysius. Yours truly bore witness to every second of the ‘performance’ of this celebration of the magic of theatre that started not on the boards of the auditorium but outside the Lionel Wendt Arts Centre where a torch lit skit of ritual like revelry was performed to set the mood as to what kind of rambunctious comedy was to erupt indoors once the bell rang to start the show. An introduction of sorts done in olden Sinhala folk drama style as to ‘who would be what’ in the stage play called ‘Pyramus and Thisby’. The troupe of thespians found in Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ thus announced their birth as bilingual Sri Lankans to set the pace for what is an innovation ‘inspired’ by Shakespeare’s celebrated comedy, though perhaps not a fully fledged adaptation.

From the very outset it was clear that this was a labour of great passion displaying skill and planning on the part of the theatre company, Centre Stage Productions headed by Aloysius. Yours truly bore witness to every second of the ‘performance’ of this celebration of the magic of theatre that started not on the boards of the auditorium but outside the Lionel Wendt Arts Centre where a torch lit skit of ritual like revelry was performed to set the mood as to what kind of rambunctious comedy was to erupt indoors once the bell rang to start the show. An introduction of sorts done in olden Sinhala folk drama style as to ‘who would be what’ in the stage play called ‘Pyramus and Thisby’. The troupe of thespians found in Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ thus announced their birth as bilingual Sri Lankans to set the pace for what is an innovation ‘inspired’ by Shakespeare’s celebrated comedy, though perhaps not a fully fledged adaptation.

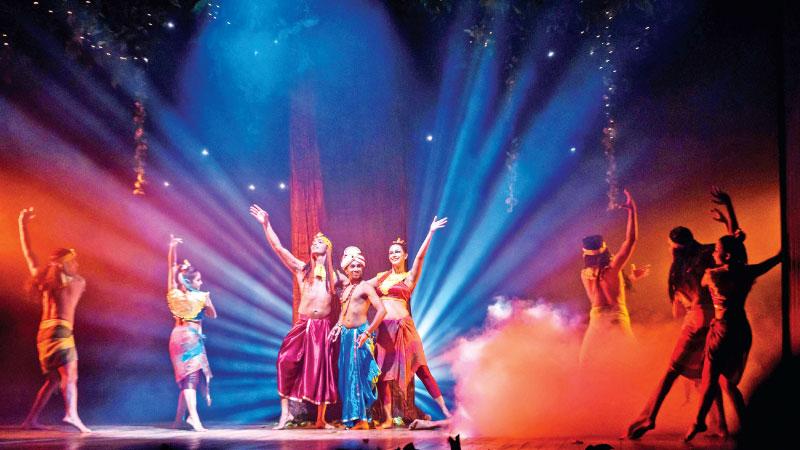

The production’s motif was consistent in carrying forth the theme and idea of enchantment through music, choreography, costumes, and lighting which had the motive of mesmerising the audience. The wondrous dance scenes of the fairy folk were dazzling displays giving motion to form and colour with rhythm. The impressive choreography included agile and dexterous acrobatic moves evincing much planning and rehearsal being committed to realise the vision of this production. Garbed in stunning costumes of eastern designs, Roshni Gunaratne as Titania, the queen of the fairies, and Kavishka Perera as king of the fairies, Oberon, proved a spectacular couple as fairy folk royalty gracing the stage with notable artistry of dance, together with their respective entourages of fairy folk. Dance in this stage play was not mere ornamentation. It was part of the non verbal communication, adding to the fabric of performance as part of the ‘non verbal text’ of Aloysius’s work. Amity and amorousness between the king and queen of fairies were visible as much as their animosities when the scenario occasioned it.

Oberon and Titania displayed elegance of rhythmic motion and spoke dialogue that was stylised and sounded ‘ornate’ and rehearsed. The strengths of Gunaratne and Perera as artistes in this performance I believe came out mostly through the element of dance.

However, one may view this stylised dialogue (by which I do not mean the diction, which was Shakespearean, but the manner of enunciation and delivery) as a possible rendition of the surreal nature of the fairy folk as opposed to the ‘humanly real’ characters in Quince’s troupe. Thereby, one may say Aloysius designed schemes for dialogue style to differentiate the nature of character categories. If that was the case, then yes, it was successful.

The character of Puck aka Robin Goodfellow, played commendably by Dion Nanayakkara, was in my opinion a dialogically underdeveloped and underutilised role. More verbal contribution to the text from this colourful character would have been welcome.

The non verbal narrative aspect of the play included an authentic traditional olden Sinhala folk cultural element in the form of a Naaga Raaksha dance (devil dance) complete with a traditional drummer. This element takes place before Titania awakes from her sleep and sees Bottom with whom she falls in love. It was perhaps meant to serve as a dream unfolding in slumbering Titania. However, I cannot help but feel it appeared superimposed upon the story narrative as an ‘exotic element’ for the sake of showcasing Sri Lankan ritualism. It was more ornamentation than narrative.

‘Pyramus and Thisby’ cannot be called an English Sri Lankan play. It is patently a Sinhala–English bilingual play. It is a reflection of contemporary Sri Lanka. Works of Sinhala–English bilingual theatre require an audience to be competent in both Sinhala and English as mediums of verbal communication, and thereby specifically addresses Sri Lanka’s ‘urbane urbanism’.

‘Pyramus and Thisby’ had a spectrum of language variance where Shakespearean diction (of ‘thou art’ form) juxtaposes with rustic bawdy colloquial Sinhala! The text showed layers of language that is creditable of Aloysius as a playwright. Shakespearean diction was principally the preserve of Oberon and Titania and contemporary English parlance and substandard Sri Lankan English, which included erroneous enunciation and mispronunciation of English words which was ascribed to Quince’s troupe. Aloysius’s script showed his brilliance in writing comedy for the Sri Lankan pulse.

The comedy generated by this play worked at many levels. There were scripted mishaps and admissions characteristic of meta-theatre, slapsticks, witticism and tomfoolery, as well as, bawdy language and gestures that were sexually nuanced. How much of that was vulgarity, and how much of it rambunctious comedy I will not judge. On that matter, I feel each should decide on their own how qualified the performance was to be a show for the whole family. Another aspect to note is that there was a pervasive homoerotic vein woven into the demeanours of Peter Quince and his minions. Quince, played by seasoned actor of the English stage Anuk de Silva, was no doubt entertaining, but was at times a tad overdone in ‘playing the pansy’; thus losing the spark of the ‘drama queen’ with too many over the top theatricalised projections of the character’s ‘orientation’.

Bottom, who was the life of the party, was played with exponential skill by Jehan Aloysius. He had his audience in raptures. Here is an actor who knows how to commandeer every second of his presence on stage to make it perceived and purposeful. Aloysius’ (very) being as an actor shone that evening as though every atom in his body was designed to give life to his character. I would say in general the players on stage all did a decent job and showed no detectable signs of stage fright or visibly poor acting.

The part where Titania sees Bottom after waking up from her sleep and is love struck due to the love potion administered on her, and begins spinning her allure to seduce Bottom, gave way to a notable facet of masculine politics. Bottom’s behaviour showed a form of postcolonial rustic masculine confidence. Titania was speaking in Shakespearean English and Bottom was being a lovably rustic macho man who wasn’t overawed by the enchanting female’s sophistication. Bottom saw Titania’s behaviour as ludicrous saying in Sinhala “Me genita pissu!” which would translate to English as ‘This woman is mad’. Bottom’s self confidence was not unsettled by the sophistication displayed before him. As I see it, that part was a symbolic nuance of the strength of the primordial man.

What were the ‘politics’ of this play? Many are focused on dissecting the ideological underpinnings of a work of art presuming that every work of art ‘must have’ socio-political ‘messages’ embedded into it. Based on my observations this appeared more a work of aestheticism than didacticism.

Stagecraft was designed to show one principal setting – the forest, characterised by an impressive centrepiece, a tree, around which unfolded, in minimalist design, settings with props such as Titania’s royal bed, to suit different moments in the narrative. Stagecraft was thus designed to show an arboreal environment of the fairy folk into which Quince’s troupe was immersed. It was a very technically sound approach that utilised space and light to maximum advantage to project mesmerising scenes.

I shall now move on to comment on an aspect of this production which I believe warrants censure, as a ‘stunt’ devised an ‘audience participated scene’. At a certain point in the play Peter Quince declares the need to hold an audition to fill the shoes of Bottom whom he fears has walked out of the production. What ensued seemed at first an innocuous ‘search’ for volunteers from the audience with Quince and his men looking for suitable candidates to get on stage and audition for Bottom’s role as Pyramus in the drama they planned to stage. But as there did not appear to be any viewers wholeheartedly volunteering with spontaneity, the thespians proceeded to coerce viewers to become participants in the ‘performance’.

Three gentlemen from the audience were brought up on stage by the actors playing Quince’s henchmen. Quince then proceeded to ‘audition’ each of the three ‘participants’ by subjecting each of them to tests. From the looks on the faces of the three gentlemen who were taken up to the stage it was evident that they were considerably uncomfortable with the onstage situation they were trapped in.

Audience members have a right to watch the show without being dragged out of their seats and subjected to the dictates of trained artistes. Thespians must realise that in their zeal to break the fourth wall and experiment with audience participation cannot turn their viewers into playthings to be dragged on stage, kept prisoner and subjected to their dictates.The will of the artistes cannot be imposed upon laymen in the confines of a ‘performing space’ where the ‘artiste is king’.

There may be different views on this matter depending on points of observation.

Looking at the overall picture (discounting the aforementioned stunt of course), taking the performance as a work made up of dialogue, music, dance, together with the whole visual component projected from the stage, what was ‘Sri Lankan’ about ‘Pyramus and Thisby’? In terms of dialogue, Sinhala was integral to the scenario. There was Sinhala and English ‘code-mixing’ as well as ‘code-switching’ done with accurate grammatical structural integrity characteristic of natural bilinguals. Costumes, styles of dance and music were of an eastern form.

It is a production with overtones of eastern aesthetics, built on a story idea extracted in part from Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, fusing different layers of language from two cultures to create a work that was innovatively urban Sri Lankan. This was innovation that showed originality. Original theatre in Sri Lanka must be supported and applauded. Through ‘Pyramus and Thisby’ Aloysius and his team presented a work that is a credit to Sri Lankan theatre. And for the record, this production elicited at end of the curtain call, a standing ovation from the (re)viewer who occupied seat E 12 that night at the Wendt.