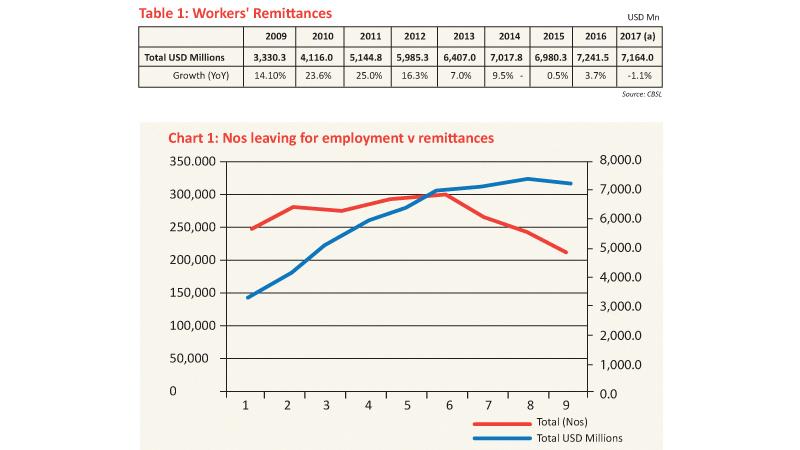

Central Bank data shows that migrant remittances contracted by 1.5% in the period January - September 2018 compared to the corresponding period last year. We seem headed for a second successive year of decline - inflows contracted by 1.1% in 2017.

After growing at almost 20% year on year between 2009-12, growth slowed to single digits in 2013-14 and fell by 0.5% in 2015. After a slight recovery in 2016 earnings contracted again in 2017 (by 1.1%). They have continued to decline in the nine months of 2018.(See Table 1)

Remittance flows are substantial, so a decline is a cause for concern, carrying implications at both the Macro and Micro level.

Remittances amount to 8.6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and are the country’s second largest source of export earnings (merchandise exports are worth around US $ 11bn while remittances are around US $7bn annually). In contrast, tourism only generated US$ 3.9bn in 2017.

According to estimates by the Sri Lank Bureau of Foreign employment, around 1.5 million people, (almost 20% of the labour force) are employed overseas. One in ten households is estimated to benefit from remittances which also make an important contribution to reducing poverty.

The numbers leaving for foreign employment have declined since 2015. This coincides with the stagnation in growth in earnings.

Two factors are affecting the number of workers departing (See Chart 1)

The economic downturn and labour market reforms in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, which have led to reduced demand for labour, and the restriction imposed by the government which has stemmed the outflow of females migrating for domestic work. In June 2013, the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE) introduced a regulation known as the ‘Family Background Report’ (FBR), which prevented women with children under five years from migrating for domestic work overseas. The number of females leaving for work has declined steadily since then. This is visible in the table below.

In 2012, (the year before the FBR was imposed) departures by females were 138,312 but by 2017 departures by females had fallen to 72,891. We cannot draw a firm conclusion linking the decline in remittances to the FBR on this preliminary data but it is a matter that deserves further investigation. It is also worth questioning the necessity of the FBR. (See Table 2)

Pressure to restrict migration has been building for some time. It is argued that the disintegration of migrant workers’ families, particularly female workers, has had adverse repercussions, such as children’s well-being and the misuse of remittances by spouses (Gunatilleke, Colombage, and Perera, 2010)

In 2007, the Ministry of Women and Child Affairs (MWCA) sought approval from the Cabinet to ban women with children under five, from migrating overseas for work, citing the negative Social Costs on children when the mother is absent.

Knee-jerk reaction

Although not approved at the time, this appears to have reemerged as the Government’s response to the execution of underage female domestic worker Rizana Nafeek in 2013, in Saudi Arabia.

Like far too many policies, the FBR is an arbitrary, knee-jerk reaction with little examination of the wider issues. In this instance the problem and response are not connected to the same issue. The FBR has come in for criticism from many quarters including the UN and ILO for being discriminatory. It may also be counter-productive.

Responding to a question in Parliament, the then Deputy Minister of Telecommunication, Digital Infrastructure and Foreign Employment Manusha Nanayakkara said many women whose applications were rejected due to the FBR, had travelled to the Middle East using forged documents and visit visas.

It is bad enough that female domestic workers are a vulnerable group. “An almost universal feature is that domestic work is predominantly carried out by women, many of whom are migrants or members of historically disadvantaged groups. The nature of their work, which by definition is carried out in private homes, means that they are less visible than other workers and are vulnerable to abusive practices.” (ILO).

When they are forced into illegal channels it is even worse. Illegal migrants will not enjoy even the minimal protection afforded by the law. If the FBR is incentivising illegal migration, the risk of exploitation increases further.

Corruption

Women are driven to seek overseas employment out of sheer necessity. A submission by a group of civil society organisations contends that “in many situations, the women and their families simply have no alternative source of income to care for the children and the family.

Alternatively, the women are facing abuse or exploitation at home and are in search of an escape”.

The intrusive process of obtaining an FBR creates further pressure and incentivises corruption. The process includes certification of Civil Status by a Grama Niladhari, a submission with further supporting documents to a Development Officer (DO), approval by a committee of the Divisional Secretariat (DS) and a visit by the DO to verify the information.

In practice, the situation is even worse. There is a myriad of documents the women have to submit, beyond those specified in the circular and the process requires multiple visits to the DS. Women are required to nominate a guardian but the ILO notes: “Women encounter long delays and questions on their ability to appoint a proper guardian for the children. In cases where the husband was present, the men were frustrated with the insistence on the part of the Government to appoint an additional female guardian for the children”.

The capacity of the DO to make judgements on the ability of the family to look after the children left is also questionable. Unsuccessful candidates have an appeal process, to a committee that according to ILO data may have to review as many as 75 cases a week.

Migrants have reportedly resorted to using transit destinations (India, the Maldives) and visit visas to circumvent the regulations which may mean higher costs for workers as well as increased risk.

In August, the Government said that a sub-committee has been appointed to evaluate the possibility of doing away with the FBR, which is timely and welcome. The Government must also address the broader underlying problem.

Overseas employment is a solution to economic problems faced at home, unemployment and or underemployment, high inflation, indebtedness and lack of access to resources.

If there are sufficient well-paying jobs at home there is no need to seek work overseas. Jobs are created when there is new investment, therefore, dismantling the barriers to investment is the key.

Complementary to this is ensuring that the Cost-of-Living is manageable which means dismantling protectionist policies that have resulted in unnecessarily high cost of food and other essentials.