Every day, on my way to work, I would pause the music I was listening to while we drove past one particular wall. I knew it well –white, with the outlines of skipping schoolchildren painted on. Even though the paint cracked and grew dull over the years, my eyes would instantly find it no matter how fast we drove past.

It was only when we turned the corner on to Katukurunduwatte Road, where the Sunday Leader office was located, that I would turn my music back on.

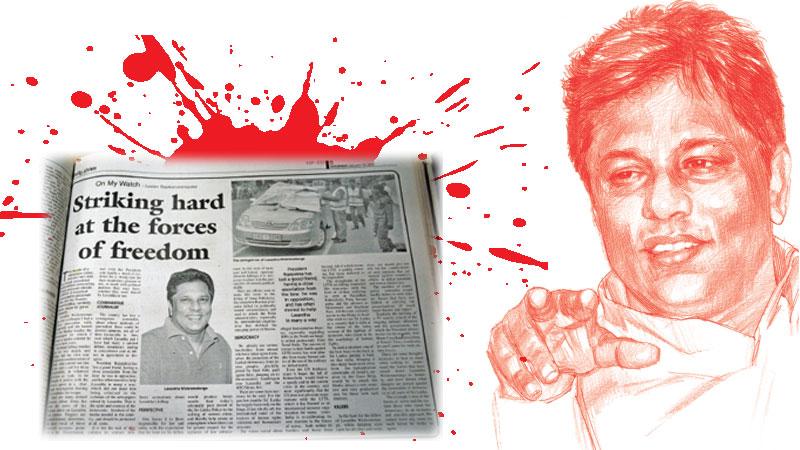

The route I regularly took to work was very similar to that of my Uncle (Baappi as we called him). Every day, it took me past the wall where he was shot.

The route I regularly took to work was very similar to that of my Uncle (Baappi as we called him). Every day, it took me past the wall where he was shot.

I don’t remember when I first hit pause. Perhaps it was on the first day I reported to the Sunday Leader office after his death. As I waited for the lift, I recalled with painful clarity a conversation in which Baappi said he was thinking of migrating to Australia. There was no way I’d work here without him, I remember thinking.

To me, he seemed as integral to the office as the narrow balcony where the older journalists took smoke breaks, or the tea room with its peeling table where we would often retire for inspiration (or, if you worked the night shift, for roti or stringhoppers from the nearby shop.)

Baappi belonged behind his heavy desk with the glass top, strewn with innumerable papers, and with his mobile phone semi-permanently clenched to his ear. It was an odd experience to walk into the building and sit steps away from his office, knowing that he was now irrevocably, permanently absent. I knew if I were to walk in, I would see the same heavy desk, that same chair.

It felt almost as if he had just stepped out to chase down a story.

After Baappi died, the editorial staff went to the office on Katukurunduwatte Road and finished that weekend’s edition, as they always did.

Years later, while reading about the Capital Gazette shooting, I would feel a pang when I read reporter Chase Cook’s tweet.

“I can tell you one thing. We are putting out a damn paper tomorrow.”

That was the spirit of defiance actively encouraged at the Sunday Leader. This many readers did agree on, even as they disagreed with the Leader’s politics or content.

On my last day at the Sunday Leader in 2013, I grappled with guilt. It was the same sensation of guilt I felt when I realised that, for the very first time, I had forgotten to press pause when we went past that white wall.

I worried that I would, similarly, forget the cadence of Baappi’s laugh, or the exact tone of his voice. I worried that in choosing to leave, I was letting him down.

As much as I wanted to pause, eventually I had to move forward. Not with the intention of forgetting or leaving Baappi behind, but of recalling the lessons he (sometimes inadvertently) taught me.

One of those lessons included looking outward, rather than solely or selfishly inward. In my private grief, I had forgotten that there were others who had been silenced.

Aiyathurai Nadesan, Bala Nadarajah Iyer, Dharmaratnam Sivaram, Mylvaganam Nimalarajan, Paranirupasingham Devakumar, Relangi Selvarajah, Selvarajah Rajeewarnam, Subhash Chandrabose and Subramaniyam Sugithirajah.

Nine journalists were killed for their work since 1992, apart from my Uncle, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s not counting those who were killed in crossfire or while on a dangerous assignment – adding those names increases the count to 19.

JDS Lanka has more names – over 40 journalists and media workers. That’s not counting those who were tortured or fled the country or who were abducted. Few pause to recall these names more than once a year, and then they are often grieving family members or colleagues.

Few of these cases have really seen progress. Ten years later, the Sunday Leader has folded. With time, bolt guns were replaced with other, equally effective tactics.

But every year on January 8, there are still those who pause to remember.

2019 will be a key year. Now more than ever, Sri Lanka needs those willing and able to ask difficult questions. And this country needs to provide the space to ask them. Not doing so will mean returning to a time of violence.

Let us all strive for better.

****

The grief is still real, says Lasantha’s daughter

|

|

Its hard to believe it’s been 10 years since my father’s passing. It’s hard to put into words how surreal a decade feels when the grief is as real and consuming as it was the day he died.

It’s hard when images of a crime scene are embedded in your mind; I don’t know if they will ever fade and if I can ever truly live in peace.

So many memories I shared with my dad have been clouded by trauma and the dirty politics surrounding his murder. We still miss him as we did the day he died, and we will not miss him any less in another ten years.

– Ahimsa Wickrematunge