During the past 30 years, about 40 countries that underwent contemporary processes of political, ethnic or religious violence began a transition to democracy, while simultaneously conducting a review of their recent past. Among the best known are Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, Guatemala, Peru and Colombia in Latin America, South Africa, Rwanda and Sierra Leone in Africa, the Balkan states in Eastern Europe, Cyprus in Western Europe, and East Timor in Asia.

During these processes, conducting investigations into what exactly happened to the victims of enforced disappearance and/or extrajudicial executions has been key in gaining insight into the truth, determining criminal liabilities, and receiving redress. Unfortunately, victims of enforced disappearances are not found, in most cases, or are mostly found dead, buried in graves, or disposed of in rivers, lakes, volcanoes, or the sea.

Finding the remains and identifying the victims are particularly sensitive issues, as they touch upon some of the most painful and distressing feelings of the victims’ relatives, i.e. the uncertainty as to whether their loved ones will be dead or alive, the impossibility of burying them according to their family rites, and the absence of justice. Looking for a living person, a task that involves hope, is very different from looking for a dead person, with its terrible certainty.

Science has played a key role in investigations, thanks to the application of different scientific forensic disciplines relating to medicine, ontology, archaeology, anthropology, and genetics, among others. As a result, it has been possible to locate clandestine mass graves, exhume buried bodies following proper methods, and analyse remains to identify them and to establish the cause and manner of death.

These processes face several challenges around the world, from the lack of political willingness to provide concrete answers to the families of the victims, to technical aspects related to the identification process of the recovered bodies. In that sense, the experiences accumulated have shown that one of the most complex aspects is the relationship between the families of those who have been made to disappear, and the forensic experts who have been tasked to recover and analyse the bodies.In order to improve dialogue and create understanding about the needs of the families and the limitations of the forensic work, it is important to develop a strategy with an open and transparent dialogue, where all doubts of the families are addressed and a clear channel of communication is established to enable families to learn about the progress of the cases and to receive explanations as to how the bodies are identified. At the same time, forensic practitioners must be able to explain the investigation process, its limitations, times constraints and all possible outcomes.

Many cases around the world have shown that respect for diverse cultural and religious rituals relating to the treatment of dead bodies is critical to uphold the dignity of the dead,as well as that of the community. In that sense, it is good to highlight that exhumations and the analysis of the recovered bodies are not just technical operations but have wider political, judicial, psychological, cultural and religious implications.

The lessons learned during the past three decades of having applied forensic sciences to the investigation of cases of political, ethnic and religious violence in diverse contexts,have shown that there is no unique strategy to deal with the search and identification of the disappeared. Instead, it has shown that there are some best practices common to all. The central role played by the families of the disappeared in the entire process, by not just providing biological samples for the identification, but also by participating in discussions where the mechanisms of the process are defined, along with the the need to have an autonomous body in charge of the whole process (with a long term vision), adequate funding and sufficient human resources, pushing the need to have a full-time dedicated group of forensic experts with multidisciplinary perspectives towards investigations their drive to create Forensic Data Banks with Ante Mortem and Post Mortem information in a single Data Base, (instead of only Genetic Data Banks), the need to incorporate cultural,religious and gender perspectives into the whole process , are some of the many ‘best practices’ a team must be informed of to avoid merely copying models from other contexts.

Truth, Justice, Reparation, Memory and Reconciliation are the main values that any society moving from a traumatic past to a new democratic and peaceful period must face and effectively implement. It is in fact a long road, but the only one that will help build a democratic society.

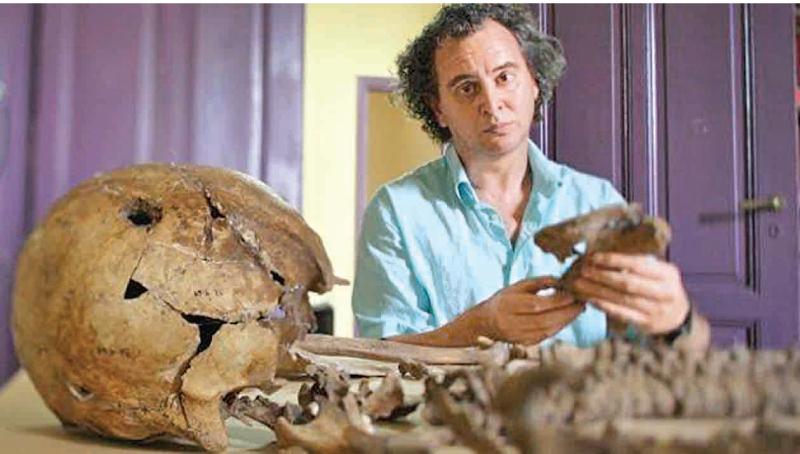

Dr. Luis Fondebrider is an internationally renowned forensic expert who has worked in multiple contexts across the world. He is a founding member and President of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) and is also the Director of the Course in Forensic Anthropology, at the Medical Faculty, University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). At an event organized by the Office on Missing Persons yesterday, held at the BMICH, he delivered a lecture on the importance of respecting humanity in the scientific search for truth.