The existence and relevance of truth in art is an interesting way of showcasing how it is able to communicate to its viewer and audience. An absence of an absolute expression of honesty leaves room for interpretation, ambiguity, questions and conversations. The surrealists question what truth is and what its source. René Magritte in his ‘treachery of images’ questions the connection between initial perception and original intent. The unreliable narrator is one means, often employed in literature. Humbert Humbert in Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Lolita’ is a prime example of an unreliable narrator - one who hides his perversions in the poetry of his language.

The existence and relevance of truth in art is an interesting way of showcasing how it is able to communicate to its viewer and audience. An absence of an absolute expression of honesty leaves room for interpretation, ambiguity, questions and conversations. The surrealists question what truth is and what its source. René Magritte in his ‘treachery of images’ questions the connection between initial perception and original intent. The unreliable narrator is one means, often employed in literature. Humbert Humbert in Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Lolita’ is a prime example of an unreliable narrator - one who hides his perversions in the poetry of his language.

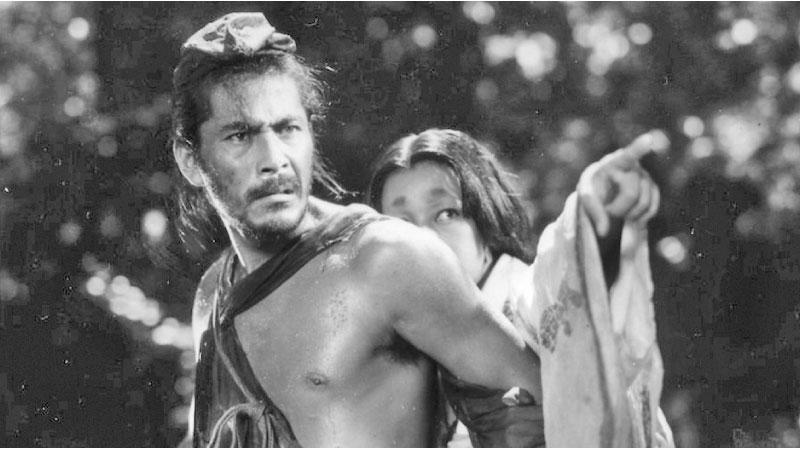

In the medium of film however, audio, visual and psychological elements combine in Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 thriller - Rashomon which exploits not just one, but at least four unreliable narrators who lie, or rather present ambiguous versions of truth that embody a sense of nihilism and hopelessness. The influence of Kurosawa’s film extends far beyond his craft. From its reputation as a forerunner of the international art house film culture, and its recognition from critics and scholars, there is little the writer of today can assess that hasn’t been discussed and praised before. Yet, just as in the feudal Japan portrayed on screen, and the post war world of the film, its ability to observe contemporary issues, as it was then, is both relevant and evident.

The film features 4 different accounts of one story. The vague basis of which is that a man is murdered, and a woman is alleged to be raped. The notorious bandit Tajomaru is the obvious suspect.

He even testifies in court - the sequence of events that led to the tragic outcome. Yet as the larger story of the film progresses and other testimonies follow, what occurred on that fateful day becomes more and more murky - truth is presented as something subjective.

The title of the film - Rashomon is the name of the southern city gate that led to the then capital city of Japan - Kyoto. The gate is a ruin. A reminder of times passed. Its great and imposing imperial architecture tells a great story and its state of ruin and destruction tell a tragic one. It is under this - (a symbol of an age in decline )in the refuge of a thunderstorm, a multi layered story is shared around a fire.

At the fire are a woodcutter – (the witness to the scene of the crime), a cynical villager, and a priest who’s lost faith in the soul of man. Three men affected by the larger happenings of their universe, but with no control of its events.

Kurosawa’s language in the film is not of his heritage, but of his art. Metaphors and motifs speak more truth than the characters do. Sunlight and shadows, summer heat and torrential rain interpret elements central to the film. The forest where the woodcutter stumbles upon the scene of the crime, with its thick foliage is in itself symbolic of the truth shrouded by the jungles of the mind. Good and evil are told through a reflection of subjective and objective truth.

These moral questions take such centre stage, that the murder of the man takes a backseat. Like the cynic points out early on - “just one man, so what? On top of this gate you will find at least five or six unclaimed bodies.” Such is the disregard for life, and the regard for morality.

Rashomon is not a film that answers questions, but one that questions answers. Its strong postmodernist themes and existential undertones are clearly relevant to the world today considering recent events. Just as truth is painted as a subjective point of view, hope and redemption in a black and white world are to be found in the humility of personal actions.

Kurosawa is arguably the most timeless of his Japanese contemporaries. While, like him, Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa discussed the challenges of a post war Japan, Kurosawa’s films showcased a firm Japanese identity in a larger world. His films were about Samurai, yet at their core, were observations of mankind’s loss of morality and higher purpose. Tragic outcomes were central to the Kurosawa film, yet redemption was ever present in the characters that manifested the flawed universe of the auteur’s picture.

Authors the world of Rashomon is bleak. Its story offers only questions, but no solution, its characters are soaked in despair and speak in falsehoods. Yet everything all draws to a close, the rain ceases and the sun shines; the viewer is forced to accept a sudden turn of events. A new life is embraced by one who was once lost.

The film ends with the question of whether this is a symbol of redemption for one man or all of mankind.

The film Rashomon (1952) was directed by Akira Kurosawa and stars Toshiro Mifune as the bandit Tajomaru, Takashi Shimura as the woodcutter, Machiko Kyo as the woman and Masayuki Moro as the Man.