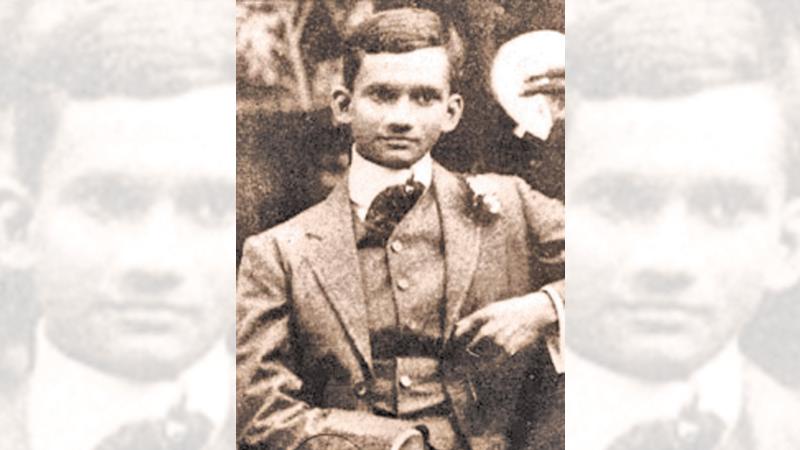

On July 7, 1915, which eventually became a phrase signifying a major calamity or Julie Hathai, is one of the darkest days in the annals of Sri Lankan history, on which date, young Edward Henry Pedris, aged 28 (1887-1915) and a scion of an elite Sinhalese-Buddhist family in Colombo, was assassinated by a Panjabi firing squad, consequent to an unlawful sentence passed by a Court Martial.

Incidentally, about 100 years previously on March 2, 1815, the British solemnly undertook to protect Buddhism, but did exactly the opposite by repressing the Sinhalese-Buddhists majority. In May, 1915, an insignificant local skirmish between the Sinhalese and the Muslims near the Hill Street Mosque in Kandy had developed into large scale communal riots island wide.

Incidentally, about 100 years previously on March 2, 1815, the British solemnly undertook to protect Buddhism, but did exactly the opposite by repressing the Sinhalese-Buddhists majority. In May, 1915, an insignificant local skirmish between the Sinhalese and the Muslims near the Hill Street Mosque in Kandy had developed into large scale communal riots island wide.

Colonial Governor Sir Robert Chalmers had declared martial law and handed over the law and order situation to Brigadier General Leigh Malcolm, the General Officer Commanding the troops in the Island. A state of terror was unleashed by the military and without discrimination, people were shot at sight.

A series of Kangaroo Courts under the grand name of “Field General Court Martial” (FGCM)was convened and in which their Lordships, the members of the Court Martial, though they had already convicted the accused before the trial, nevertheless proceeded to try him in a manner befitting to a Court of Justice. Henry Pedris too had the misfortune to come before such a Field General Court Martial.

He was found guilty and shot down on July 7, 1915 at the Welikada Prison by a firing squad composed of Panjabi soldiers of the British Army.

The Field General Court Martial that tried Pedris was totally flawed and even the purported death sentence was not confirmed by the competent authority, the Governor of Ceylon. A docile Ceylon Supreme Court in the form of Sir Alexander Wood – Renton C.J, Justice Shaw and Justice de Sampayo erroneously declined to interfere with the sentences passed by numerous Field General Courts Martial citing lack of jurisdiction.

This article will mainly focus on the legal infirmities of the Court Martial that tried Pedris and the judgments made per incuriam by the Ceylon Supreme Court declining to interfere with the sentences passed by Field General Courts Martial that were convened during the martial law period, 100 days from June 1915 to August 1915.

Field General Court Martial

Riots broke out in Kandy on May 28, 1915 and soon spread to Colombo and other parts of the Island. Two groups of Sinhalese and Muslims had clashed in Pettah near Pedris’ shop and when the safety of the shop was threatened, Pedris fired two shots into air using his revolver and the mob dispersed.

Pedris was soon arrested and brought before a Field General Court Martial composed of British Army officers stationed in Ceylon on an Indictment containing five counts inter-alia, treason by levying war against Our Lord, the King (levying war by firing two revolver rounds into the air!).

The offences were said to have committed on June 1, 1915. The martial law was declared on June 2, 1915 and the proclamation did not specify that it had retrospective operation and it is trite law under the English law that an Act or Order has no retrospective operation unless it is clearly so spelt out on its face.

Thus Pedris’ trial was abintio void because at the time of the alleged offence, martial law was not in force in Ceylon.

The Field General Court Martial (FGCM), composed of British officers of 17th Panjab Regiment (an Indian Regiment of the British Army) stationed in Colombo, was held at the Headquarters of the General Officer Commanding Troops Ceylon which was located at the present Defence School building at Malay Street, Slave Island. Unlike a General Court Martial (GCM), which must be presided over by a Judge Advocate General (JAG), for FGCMs, the presence of a JAG is optional.

In the FGCM of Pedris, there was no JAG and the Court Martial Board was entirely composed of lay Army officers who were not conversant in the law. Pedris was found guilty of the charge of treason and sentenced to death. In the court martial, Pedris was defended by Advocate L.H. de Alwis.

Unlawful execution

Pedris was tried under and in terms of the Army Act (1881) UK. In terms of the Army Act, a death sentence passed in a British colony had to be ratified by the Governor of the Colony. In addition, Pedris was a member of the Colombo Town Guard, which was a unit raised under the Ceylon Defence Force (CDF) Ordinance and no sentence of a court martial awarded in Ceylon for the trial of any member of the CDF shall be carried into execution unless confirmed by the Governor of Ceylon.

Despite this mandatory requirement, the General Officer Commanding Ceylon, Brigadier General Leigh Malcolm did not refer Pedris’ case to the Governor for him to consider exercising clemency of the Crown. Governor Sir Robert Chalmers protested over this omission and other cases came to be referred to him after this.

Thus it is submitted that the execution of Pedris was unlawful since the death sentence was never confirmed by the Governor of Ceylon.

After his conviction by the Field General Court Martial, the relatives of Pedris immediately filed an application for Writs of certiorari and prohibition in the Ceylon Supreme Court, but the relief was denied by a bench comprising Sir Alexander Wood – Renton Chief Justice, Justice Shaw and Justice de Sampayo.

This judgement was never published in the New Law Report. Nevertheless, erroneous reasoning of the Supreme Court can be inferred from two Field General Court Martial cases related to a prominent VIP W.A.de Silva and Edmond Hewawitharana, an uncle of Pedris and a kinsman of Anagarika Dharmapala (Don David Hewavitharana). Anagarika Dharmapala had a narrow escape since at the time he was in Calcutta.

This judgement was never published in the New Law Report. Nevertheless, erroneous reasoning of the Supreme Court can be inferred from two Field General Court Martial cases related to a prominent VIP W.A.de Silva and Edmond Hewawitharana, an uncle of Pedris and a kinsman of Anagarika Dharmapala (Don David Hewavitharana). Anagarika Dharmapala had a narrow escape since at the time he was in Calcutta.

A writ of habeas corpus was filed on behalf of W.A. De Silva. Adrian St.V. Jayawardane, paternal uncle of President J.R. Jayewardene, supported the application.

The Supreme Court issued notice to the military but later refused relief on the ground that; Per Sir Alexander Wood Renton C.J. (on 29th June 1915); “when martial law involved, the function of the municipal courts is limited.

They have the right to inquiry and the duty to inquire into the question of fact whether an “actual state of war exists or not”.

Once that question has been answered in the affirmative, the acts of the military authorities in the exercise of their martial law powers are no longer justifiable by the municipal courts”.

A writ of prohibition was filed by Eardly Norton, a well-known barrister of Madras bar on behalf of Hewawitharana. Again the same three judges declined to interfere on the ground that “Ceylon Supreme Court had no power to issue writs against a court martial”.

It is submitted that the above two decisions are wrong and totally inconsistent with well-known English judgements on martial law and courts martial cases:vide R v Cowle (1759) 2 Burr 835, The Case of Theobald Wofle Tone (1798) 27 How St Tr 613; In re Anderson 7 Jur NS 122.

In the local case of DC Negombo 221 Grenier (1873) DC 122,Sir Edward Creasy C.J. held that with regard to power of issuing writs, the Ceylon Supreme Court was in a position similar to the Court of Queen’s Bench in England.

In any case, if the Ceylon Supreme Court was uneasy of a martial law matter, they could have referred the same to the Privy Council (the apex court for the Island of Ceylon at the time) ex mero motu while staying military proceedings locally.

The legal defence of Henry Pedris, Edmond Hewawitharana (his uncle) and N.A. Wijesekara and N.E. Wijesekara (brothers-in-law of Mr. Pedris) were undertaken by the well- known Colombo law firm Messers D.L. and F. De Saram and composed of a galaxy of lawyers: Adrian St. Valentine Jayewerdane (uncle of President J.R. Jayewardene), Eardley Norton, a barrister from Madras bar and L.H. de Alwis and the legal cost was to the tune of Rs. 11,113.54, an enormous sum by 1915 Standards; vide A.C. Dep. Ceylon Police and Sinhala-Muslim Riots of 1915. Nevertheless the valiant efforts of the lawyers were futile. Pedris was executed on July 7, 1915 at the Welikada jail by a firing squad composed of Punjabi soldiers. He bravely faced the firing squad.

Manufacturers Life Insurance Co Ltd.

After the execution of Pedris, the administrator of his estate sought to recover from the Manufacture’s Life Insurance, an insurance company, Rs. 25,000, a massive amount in 1915, due on his policy.

The insurance company refused payment on the ground that Pedris was not eligible under the policy because he was lawfully executed.

In an action filed by the administrator of Pedris estate in the District court of Colombo (Case No DC Colombo 44358), District Judge Wadsworth upheld the contention of the insurance company and dismissed the action.

The administrator appealed to the Supreme Court and the matter came before Sir Alexander Wood – Renton C.J. And Justice Shaw, the same judges who earlier heard 1915 martial law cases. The appellant (the administrator of Pedris estate) was represented by Bawa K.C. With E.W. Jayewardene (father of President J.R. Jayewardene) and L.H. de Alwis (who defended Pedris in the Court Martial) and Skelto de Saram.

The respondent insurance company was represented by Alan Dreiberg K.C. and Samarawickrama per Wood Renton C.J. I would set aside the decree of the District Judge dismissing the plaintiff action and send the case back for further inquiries.

It will, however, be open to the plaintiff (the Estate of Pedris) to rebut that evidence by proving, if he is in a position to do so, that, in spite of the conviction, Pedris did not in fact commit treason by waging war against the King”: vide Pedris v Manufacturers Life Insurance Co (1917) 19 NLR 321.

In the District court, the insurance company, presumably under pressure from the British Government, readily settled the matter by paying the full amount.

Thus, the question with regard to the guilt of Pedris is still open.

Thus, the question with regard to the guilt of Pedris is still open.

In fact, the Pedris case set a precedent in Ceylon in that conviction by a criminal court is not conclusive with regard to civil (delictual or/and contractual) liability of a person.

Thus in Thenuwara Vs Thenuwara (1959) 61 NLR, (1960) 62 NLR 501, although Catherine Thenuwara was not indicted with murder of Dr. Thenuwara, yet in a testamentary case related to his estate, ex Captain Arthor Thenuwara, who was convicted for the murder of Dr. Thenuwara, testified against his ex-girlfriend Catharine Thenuwara establishing her complicity.

The District Judge Sivasupramanium, later Judge of the Supreme court, awarded the estate to the brothers of Dr. Thenuwara on the legal principle that a murdere cannot take under a will or succeed to an intestate estate.

Conclusions

1. It is evident that Pedris’ court martial was illegal on the grounds that:

a. In July 1915, King’s Courts were open and functioning in Ceylon and hence trial of civilians by courts martial was not permitted.

b. The alleged offences were committed on June 1, 1915 and whereas martial law was declared on June 2, 1915, it could not have had retrospective operation of law.

c. In any cases, the death sentence was not confirmed by the Governor of Ceylon and hence there was no lawful sentence before the Officer Commanding the firing squad to carry into execution.

2. Pedris was entitled to succeed had the Ceylon Supreme Court reviewed his sentence which it unlawfully declined while having the full power to review: vide cases mentioned above.

3. Therefore, this is a fit and proper case for the President of the Republic to exercise his power under Regulation 151(10 of the Court martial Regulation. “If it appears to the confirming authority that the proceedings of a court martial are illegal or involved substantial injustice to the accused and such authority has not confirmed the finding and sentence, he shall withhold his confirmation. If he has confirmed the finding and sentence, he shall direct the record of the conviction to be removed and the accused to be acquitted.”

4. In the circumstances, the President of the Republic can still clear Pedris’ name officially and legally under Court Martial Regulation 151(1) by publishing a proclamation in the Gazette to this effect. I would go further step and appeal the President to declare all those who died in the hands of the foreign invaders and enemies of the State from Chola times to May 18, 2009 in the Government Gazette as martyrs who were killed-in-action.

Recommendations

1. A Presidential Proclamation in the Gazette exonerating Edward Henry Pedris Esq under and in terms of Regulation 151(1) of Court Martial regulations.

2. A Presidential Proclamation in the Gazette declaring all those who were killed by foreign invaders and the enemies of the state, from Chola times to May 18, 2009, as “Martyrs killed-in-action” and to collectively award them the Desha Putra Sammanaya (Purple Heart), the highest medal currently awarded to killed-in-action/wounded-in-action servicemen.

3. Appointing a Presidential Commission to chronicle a list of Martyrs who were killed by foreign invaders/enemies of the State from Chola times to May 18, 2009, the Day of Liberation.

Although records might not be available with regard to earlier times, comprehensive records are available with regard to those who were killed in 1818, 1848 and 1915 insurrections and such heroes could be recognised individually by name.

This Presidential Commission may examine historians, military and other experts and compile a “Golden Book” in which a list of all martyrs will be exhibited. Those who are identified and entered in the “Golden Book” as martyrs should be awarded Desha Putra Sammanaya individually.