We are very familiar with folktales as we have a great tradition of folklore such as the stories about Andare, Gamarala, etc. Folktales originated in the people and used by the people. Because of this until very recently no folktales went into the written text. But when the literacy skills among the people were gradually developed, some erudite people started to write them.

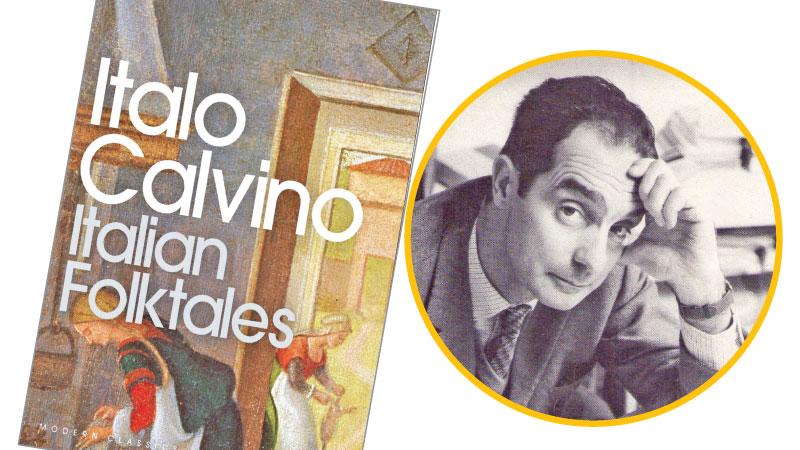

The book, ‘Italian Folktales’, in Italian ‘Fiabe italiane’ is a result of such an effort.’Fiabe italiane’ was first published in 1956 by the Giulio Einaudi publishing house though Calvino began the project in 1954, influenced by Vladimir Propp’s ‘Morphology of the Folktale’.

George Martin’s new translation was first published in 1980 and it presents two hundred Italian folktales and is a comprehensive collection of them. As the blurb of the book cover suggests, “There was no Italian equivalent to the Brothers Grimm until Italo Calvino collected these folktales from his homeland which transports the reader into a world of adventures, tricksters, kings, peasants and saints.

One of the main themes to emerge is that of love: love tested by absence and by sorcery, and love that unites the natural world and the supernatural. Retold in Calvino’s own inspired and sensuous language, this treasure–trove of folklore is considered a classic.”

Though Italo Calvino is widely known as one of the most highly praised modern Italian writers, as opposed to a scholar he ventured into compiling this book. The reason for it was stated in his introduction to the book, that it was an assignment he had to submit when he was working at the Einaudi, a major publishing house in Milan.

There were two objectives in this book project according to Calvino. It is “the presentation of every type of folktale, the existence of which is documented in Italian dialects; and the representation of all regions of Italy.” (xx)

Calvino elaborates the criteria of the work in his introduction. First, he had to select from mountains of narratives the most unusual, beautiful, and original texts. Then he had to translate them from the dialects in which they were recorded or when, unfortunately, the only version extant was an Italian translation lacking the freshness of authenticity, he had to assume the thorny task of recasting it and restoring its lost originality.

There he describes, “….I enriched the text selected from other versions and whenever possible did so without altering its character or unity, and at the same time filled it out and made it more plastic. I touched up as delicately as possible those portions that were either missing or too sketchy.

I preserved, linguistically, a language never too colloquial, yet colorful and as derivative as possible of a dialect, without having recourse to ‘cultivated’ expressions – an Italian sufficiently elastic to incorporate from the dialect images and turns of speech that were the most expressive and unusual.” (xix–xx)

Then he adds, “As the notes at the end of the book testify, I worked on material already collected and published in books and specialized journals, or else available in unpublished manuscripts in museums and libraries. I did not personally hear the stories told by little old women, not because they were not available, but because, with all the folklore collections of the nineteenth century I already had abundant material to work on. Nor am I sure that attempts on my part to gather any of it from scratch would have appreciably improved my book.” (xx)

Anyone can be aware of the seriousness of the task that Calvino accomplished. In 1980, American author Ursula K. Le Guin reviewed George Martin’s new translation and wrote in a paragraph as follows: “The Fiabe italiane was first published in Italy in 1956. My children grew up with an earlier, selected edition of them — Italian Fables, from Orion Press, 1959.

The book was presented for children, without notes, in a fine translation by Louis Brigante, just colloquial enough to be a joy to read aloud, and with line drawings by Michael Train that reflect the wit and spirit of the stories.Perhaps a reading-aloud familiarity with the cadences of this earlier translation has prejudiced my ear; anyhow I found George Martin’s version heavier, often pedestrian, sometimes downright ugly.

I don’t hear the speaking voice of the storyteller in it, or feel the flow and assurance of words that were listened to by the writer as he wrote them. Nor does the occasional antique woodcut in the present edition add much to the stories. But the design of the book is handsome and generous, entirely appropriate to the work.

Here for the first time in English all the tales are included, as well as Calvino’s complete introduction and his notes (edited by himself for this edition) on each story. The notes illuminate his unobtrusive scholarship and explain his refashioning of the material, while the introduction contains some of the finest things said on folklore since Tolkien - such throwaway lines as: ‘No doubt the moral function of the tale, in the popular conception, is to be sought not in the subject matter but in the very nature of the folktale, in the mere fact of telling and listening.’”

Calvino presents these tales in a simple and easy language, and the tales are so short that one story rarely exceeds four pages, which enables readers to finish the whole book as quickly as possible. And the other thing is that a reader can enjoy all the Italian folktales in a single volume.

As Salman Rushdie, a prominent writer says, “Calvino possesses the power of seeing into the deepest recesses of human minds and bringing their dreams to life.”In this way, ‘Italian Folktales’ opens up a path that a reader can enter into a realistic and fantastic world. More importantly, it inspires the fiction writers to explore their own cultures, own values, own traditions, and finally launch this kind of classical work that is important for the present generation as well as future generations.