Wilma Rudolph once said: “I believe in me more than anything in this world.” She sprang to fame at just 20, as the star of the Rome 1960 Summer Olympic Games, becoming the first American woman to win three gold medals in a single Olympiad. She clinched golds in blue riband events - 100m, 200m and 4x100m relay at Rome 1960 and emulated Jesse Owens who had been her inspiration. Her exceptional feat remains one of the most enduring achievements in the 124-year history of the Olympic Games. The start in her life was agonizing as it was filled with severe hardships and unequal treatment. Nevertheless, she ran, ran and ran to glory and became an iconic star.

Envision winning an Olympic medal in your lifetime - sounds great. Envision winning triple gold medals and having your name associated with world records - sounds incredible. Now, envision doing both as a 20-year-old at the Olympic Games - sounds like a fairy tale, surely. Then, envision doing all this despite the fact that you were once told as a child you might not be able to walk again because of polio. For Wilma Rudolph, these were not imaginary scenarios. She made them a reality during her glorious career. Her famous quote, “Never underestimate the power of dreams and the influence of the human spirit. We are all the same in this notion: The potential for greatness lives within each of us,” aptly describes her inspirational story.

Melbourne 1956 and Rome 1960 Olympics

In the context of Rome 1960 Olympics, she was already a winner in life, because it is no mean feat to secure an Olympic bronze medal at just 16 as the youngest member of the United States Olympic contingent. Wilma qualified to compete in the 200m at the Melbourne 1956 Olympics but she failed to do well. However, she ran the third leg of the 4x100m and won her maiden Olympic medal, matching the world-record of 44.9 sec. It was an incredible achievement for an athlete who had started running only a few years earlier.

Rome 1960 remains a milestone event in the glorious history of the Olympic Games. The interest it generated was unprecedented. It is also worth remembering that, around that time, women’s sport was not given due respect. The Olympic trials for women in the United States were not even reported. Wilma came along at a very important time in the rise of women in sports because it was the first televised Olympics. She was charismatic, had a beautiful way of running and the story of her life was so compelling that she really helped set the stage for all of the women athletes to follow.

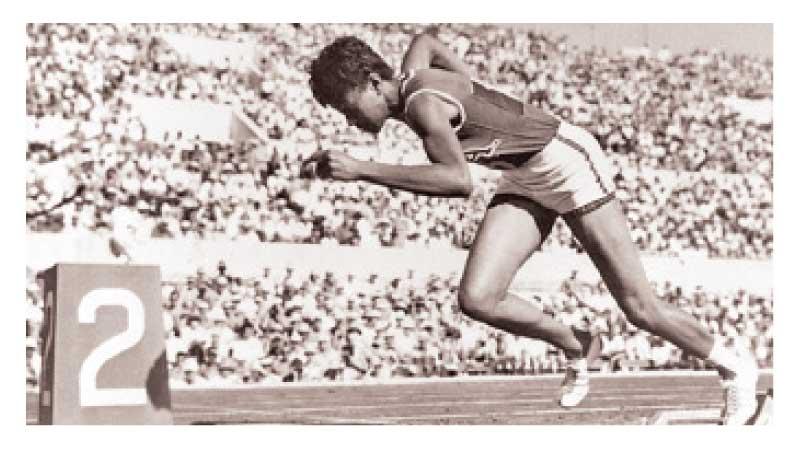

While she was still a sophomore at Tennessee State, Wilma competed in the U.S. Olympic track and field trials at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas, where she set a world record of 22.9 sec in the 200m on July 9, 1960. At the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, Wilma competed in three events on a cinder track: 100m and 200m as well as 4x100m relay, winning gold medals in all to become the first American woman to win three gold medals in a single Olympiad.

On September 2,1960, Wilma won the gold in the final of 200m with a time of 24.0 sec, after setting a new Olympic record of 23.2 sec in the opening heat. Then, on September 5, 1960, Wilma ran the final of the 100m in 11.0 sec. The record-setting time was not credited as a world record, because it was a wind-aided time. However, after these achievements, she was hailed throughout the world as “the fastest woman in history.”

On September 2,1960, Wilma won the gold in the final of 200m with a time of 24.0 sec, after setting a new Olympic record of 23.2 sec in the opening heat. Then, on September 5, 1960, Wilma ran the final of the 100m in 11.0 sec. The record-setting time was not credited as a world record, because it was a wind-aided time. However, after these achievements, she was hailed throughout the world as “the fastest woman in history.”

On September 9,1960, Wilma with her Olympic teammates from Tennessee State - Martha Hudson, Lucinda Williams and Barbara Jones–won the 4x100m with a time of 44.5sec, after setting a world record of 44.4 sec in the semifinals. Wilma ran the anchor leg for the American team in the final and nearly dropped the baton after a pass from Williams, but she overtook Germany’s anchor leg to win the relay in a close finish. Wilma had a special, personal reason to hope for victory, to pay tribute to her inspiration - Jesse Owens, the celebrated American athlete and star of the Berlin 1936 Olympic Games.

Wilma emerged from the Olympic Games as “The Tornado, the fastest woman on earth.” The Italians nicknamed her “The Black Gazelle” and the French called her “The Black Pearl”. The 1960 Rome Olympics launched Wilma into the public spotlight and the media cast her as America’s “Leading Athletic Lady” and “Athletic Queen,” with praises of her accomplishments as well as her feminine beauty and poise.

Wilma’s Inspiring Grace on the Track

Wilma Glodean Rudolph was born in Saint Bethlehem, Tennessee on June 23, 1940. She was born prematurely at 4.5 pounds and was the 20th of 22 siblings from her father’s two marriages. According to the Guardian, “even before Wilma contracted polio she had been stricken with illnesses including measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever and double pneumonia, the last two of which almost killed her.” She was fitted with metal leg braces to help her walk until she was nine.

“I spent most of my time trying to figure out how to get them off. But when you come from a large, wonderful family, there’s always a way to achieve your goals,” she said. That childhood is enough to traumatize most kids but her incredible spirit and determination took her to the heights that made the world look up in jaw-dropping awe. “Even by the extraordinary standards set by those Olympians who overcame formidable adversities, Wilma’s story is unique,” added the report in the Guardian, which also detailed the helping hands, quite literally, from her mother Blanche and siblings that helped her mend.

After making her initial mark in basketball, Wilma found her calling in athletics and made her Olympic debut at Melbourne 1956. She did not stop there. After giving birth to daughter Yolanda as a teenager, she was back on the American track team for Rome in 1960. Her sights were set on gold medals. Moreover, Rome 1960 was to be the highlight of Wilma’s extraordinary life story. Her brilliant career ended with her retirement in1962. She then got into coaching and as an icon for the African-American community, worked with underprivileged children.

Wilma witnessed Florence Griffith Joyner matching her 1960 Olympics feat of three golds in the 1988 Olympics. It filled Wilma with pride to see African-American athletes be inspired by her. “It was a great thrill for me to see. I thought I would never get to see that. Florence Griffith Joyner - every time she ran, I ran,” she said. Her grace on the track was matched by her poise away from athletics as turned into an inspirational figure for women in sport.

Wilma summed it up best in her popular quote: “My doctor told me I would never walk again, my mother told me I would. I believed my mother.” Significantly taller than most athletes, Wilma once said she was the worst sprinter when it came to starting a race. “But the farther I ran, the faster I became,” she said. Indeed, that mirrors the journey of her life too. The start was not the best, it was filled with medical hardships and unequal treatment from peers. But she raced into the history books and glory.

Birth, early life and education

Shortly after Wilma’s birth, her family moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, where she grew up and attended elementary and high school. Her father, Ed, who worked as a railway porter and did odd jobs in Clarksville, died in 1961; her mother, Blanche, worked as a house cleaner in Clarksville homes and died in 1994.

Wilma suffered from several early childhood illnesses and she contracted infantile paralysis at the age of five. She recovered from polio but lost strength in her left leg and foot. Physically disabled for much of her early life, she wore a leg brace until she was twelve years old. Because there was little medical care available to African American residents of Clarksville in the 1940s, Wilma’s parents sought treatment for her at the historically black Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, about 80 km from Clarksville.

For two years, Wilma and her mother made weekly bus trips to Nashville for treatments to regain the use of her weakened leg. She also received subsequent at-home massage treatments four times a day from members of her loving family and wore an orthopedic shoe for support of her foot for another two years. Because of the treatments, she received at Meharry and the daily massages from her family members, she was able to overcome the debilitating effects of polio and learned to walk without a leg brace or orthopedic shoe for support by the time she was twelve years old.

Wilma was initially home-schooled due to the frequent illnesses that caused her to miss kindergarten and first grade. She began attending second grade at Cobb Elementary School in Clarksville in 1947 when she was seven. She attended Clarksville’s all-black Burt High School, where she excelled in basketball and track. During her senior year of high school, Wilma became pregnant with her first child, Yolanda, who was born in 1958, a few weeks before her enrollment at Tennessee State University in Nashville. In college, Wilma continued to compete in track. In 1963, she graduated from Tennessee State with a Bachelor’s Degree in Education.

Wilma was first introduced to organized sports at Burt High School, the center of Clarksville’s African American community. After completing several years of medical treatments to regain the use of her left leg, Wilma chose to follow her sister Yvonne’s footsteps and began playing basketball in the eighth grade. She continued to play basketball in high school, where she became a starter on the team and began competing in track. Wilma’s high school coach, CC Gray, gave her the nickname of “Skeeter” (for mosquito) because she moved so fast.

While playing for her high school basketball team, Wilma’s talents were spotted by Ed Temple, Tennessee State’s track and field coach, a major break for the active young athlete. The day that Temple saw the tenth grader for the first time, he knew she was a natural athlete. She had already gained some track experience on Burt High School’s track team two years earlier. Temple invited 14-year Wilma to join his summer training program at Tennessee State. After attending the track camp, she won all nine events she entered at an Amateur Athletic Union track meet in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Post-Olympic career

Wilma Rudolph’s hometown of Clarksville celebrated “Welcome Wilma Day” on October 4, 1960, with a full day of festivities. Wilma adamantly insisted that her homecoming parade and banquet become the first fully integrated municipal event in the city’s history. An estimated 1,100 attended the banquet in her honour and thousands lined the city streets to watch the parade.

Following her Olympic victories, the United States Information Agency made a ten-minute documentary film, “Wilma Rudolph: Olympic Champion” in 1961, to highlight her accomplishments on the track. Wilma’s appearance in 1960 on “To Tell the Truth,” an American television game show and later as a guest on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” helped promote her status as an iconic sports star.

Wilma did not earn significant money as an amateur athlete and shifted to a career in teaching and coaching after her retirement from the track. She began as a teacher at Cobb Elementary School, where she attended as a child and coached track at Burt High School, where she had once been an athlete, but conflict forced her to leave the positions.

Wilma did not earn significant money as an amateur athlete and shifted to a career in teaching and coaching after her retirement from the track. She began as a teacher at Cobb Elementary School, where she attended as a child and coached track at Burt High School, where she had once been an athlete, but conflict forced her to leave the positions.

She moved several times over the years and lived in various places such as Chicago, Illinois; Indianapolis, Indiana; Saint Louis, Missouri; Detroit, Michigan; Tennessee; California; and Maine. Rudolph’s autobiography, “Wilma: The Story of Wilma Rudolph” was published in 1977. It served as the basis for several other publications and films. By now, around 20 books on Rudolph’s life have been published for children from pre-school youth to high school students.

In addition to teaching, she worked for non-profit organizations and government-sponsored projects that supported athletic development among American children. In 1981, she established and led the Wilma Rudolph Foundation, a non-profit organization based in Indianapolis, Indiana, that trains youth athletes. In1987, Wilma joined De Pauw University in Greencastle, Indiana as director of its women’s track program and served as a consultant on minority affairs to the university’s president.

She went on to host a local television show in Indianapolis. Wilma was also a publicist for Universal Studios as well as a television sports commentator for ABC Sports during the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California, and lit the cauldron to open the Pan American Games in Indianapolis in 1987. In 1992, Wilma Rudolph became a vice president at Nashville’s Baptist Hospital. Wilma prematurely died from a brain tumour at the age of 54. For her memorial service, thousands of mourners thronged Tennessee State University on November 17, 1994 and the state flag flew at half-mast across Tennessee.

Legacy, Awards and Honours

After her graduation from Tennessee State in 1963,Wilma Rudolph married Robert Eldridge, her high school sweetheart, with whom she already had a daughter, Yolanda, born in1958. Wilma and Eldridge raised four children: two daughters (Yolanda in1958 and Djuanna in 1964) and two sons (Robert Jr. in 1965 and Xurry in 1971). Wilma’s legacy lies in her efforts to overcome obstacles that included childhood illnesses and a physical disability to become the fastest woman runner in the world in 1960. She was one of the first role models for black and female athletes.

Her autobiography, “Wilma: The Story of Wilma Rudolph”, was adapted into a television docudrama in 1977. Her life is also remembered in “Unlimited”, a short documentary film of 2015 for school audiences, as well as in numerous publications, especially books for young readers. She was named the United Press International Athlete of the Year (1960) and Associated Press Woman Athlete of the Year (1960 and 1961). She was also the recipient of the James E. Sullivan Award (1960) and the Babe Didrikson Zaharias Award (1962). In addition, Wilma had a private meeting with President John F. Kennedy in the Oval Office.

She was also honoured with the National Sports Award (1993). Wilma was inducted into several Women’s and Sports Halls of Fame: Black Sports Hall of Fame (1973); U.S. National Track and Field Hall of Fame (1974) ; U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame (1983); National Women’s Hall of Fame (1994) and National Black Sports and Entertainment Hall of Fame (2001). In 1980, Tennessee State University named its indoor track in Wilma’s honor. In1984, the Women’s Sports Foundation selected her as one of the Five Greatest Women Athletes. In 1994, a section of U.S. Route 79 was named, Wilma Rudolph Boulevard.

In 1995, the Wilma Rudolph Memorial Commission placed a black marble marker at her grave site. In 1995, Tennessee State University dedicated a six-story dormitory as the Wilma G. Rudolph Residence Center. In 1996, the foundation presented its first Wilma Rudolph Courage Award. In 1997, the Governor proclaimed that June 23, be known as “Wilma Rudolph Day” in Tennessee. In 1999, Sports Illustrated ranked her first on its list of the Top Fifty Greatest Sports Figures from Tennessee.

Wilma has been memorialized with a variety of tributes. In 2004, the U.S. Postal Service issued a postage stamp, the fifth in its Distinguished Americans series, in recognition of her accomplishments. Wilma’s life has been featured in documentary films and made-for-television movies. In 2012, the city of Clarksville, TN built the Wilma Rudolph Event Center at Liberty Park on Cumberland Drive and it adores her life-size bronze statue as a living monument in her honour.

(The author highlights a spectrum of sports extravaganza and spotlight iconic athletes. He is the winner of the Presidential Academic Award for Sports in 2017 and 2018 and recipient of the National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc)