Ethnic politics is creeping into the Tamil film industry as in the controversy surrounding the making of the film 800 on the Sri Lankan cricketing legend Muttiah Muralitharan. Simultaneously, the politics of Hindutwa is threatening communal harmony in the traditionally secular or non-communal Bollywood, observers fear.

An industry which had hitherto been liberal in its values, may see a change with unofficial ethno-political censors interfering with film production and exhibition.

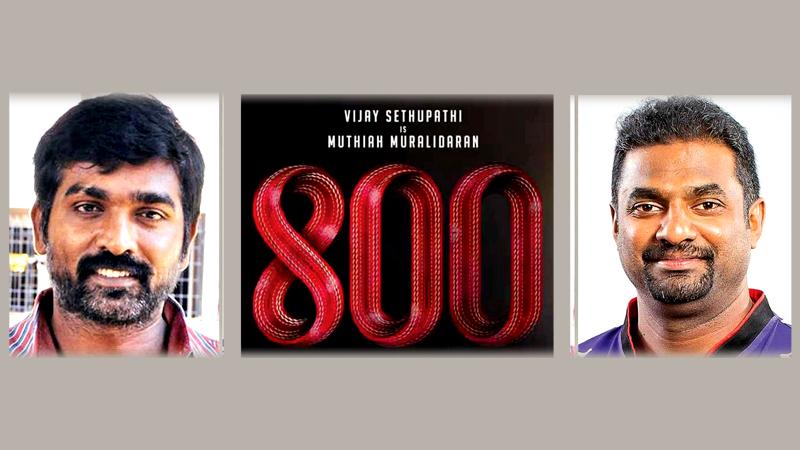

“Murali”, as the world-renowned bowler Muttiah Muralitharan is known, was trolled in the media for not siding with fellow Tamils of Sri Lanka when they were subjected to military action dubbed by pro-LTTE Tamils as “genocide”. The vicious campaign against the film, waged mainly in Tamil Nadu and the Tamil Diaspora, has led to Murali’s asking the star of the film Vijay Sethupathi to opt out of the film. Sethupathi opted out to save his skin against assaults by the Tamil extremist lobby. The making of 800 is in now hanging fire with Murali wanting the film to be made anyhow, and the producers mulling over the pros and cons of it.

Tamil Nationalist Charge

The Tamil media and pro-LTTE Tamil nationalist leaders like Seeman, leader of the Naam Thamizhar party; Vaiko of the Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (MDMK), veteran Director Bharathiraja and poet/lyricist Thamarai had slammed Murali for describing the day on which the Tamil Tigers were vanquished and the war ended as the “happiest day in his life”.

It was also alleged that he had told the visiting British Prime Minister David Cameron that Tamil women who were agitating for the recovery of their disappeared sons were “pretending”. Tamil Nadu politician Vaiko had pointed out that Murali had sided with “Sinhala-chauvinist” Mahinda Rajapaksa and supported his Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) in the last parliamentary elections. Mano Ganeshan, leader of the Tamil Progressive Alliance (TPA), said Murali campaigned for “Sinhala chauvinist” Wimal Weerawansa and against him in the last parliamentary elections in Colombo district and had put up his brother as a candidate in Nuwara Eliya district which resulted in the Tamils losing one seat there.

Murali’s critics said that the film 800 should not be only about his cricketing career with its achievements, trials and tribulations, but should include the larger struggle of the Tamils to come up in life in Sinhala-Buddhist-dominated Sri Lanka. More importantly, it should show the “genocide” at the end of the war and Murali’s insensitive and pro-Sinhala remarks about the end of the war.

Murali’s plea that he had helped educate Tamil kids in the war-affected areas and that he had been coaching them in cricket did not cut ice with his vociferous critics. Realizing that the acting career of Vijay Sethupathi, who was to play Murali in the film, was in danger as a result of the controversy, Murali issued a statement saying that he was requesting Vijay Sethupathi to drop out of the film. Relieved, Sethupthi replied: “Thanks.Goodbye.”

Forces with political agendas in mind, had denied the producer of 800 his constitutional right to free expression, Murali his right to tell his story as he wants, and the audience the right to see or not to see the film, which does not augur well for freedom and creativity in the Tamil film industry.

Wider Malaise

The scuttling of 800 reflects a wide malaise afflicting the Indian film industry as a whole in the last two decades. The US$ 2.5 billion a year industry has been coming under political pressure because of its tremendous reach and ability to shape people’s minds on a large scale. Competing political forces, unleashed by democracy, have targeted films and film makers to suppress inconvenient thoughts, ideas and opinions. These forces often decide a fate of a film, whether it will be released or not, and whether it’s content (and it’s stars) will remain as intended by the film maker. As things stand, the film maker has no absolute right to choose the subject he wants and portray it as he wants. Neither can he leave the matter to the audience to judge. The audience too has lost it’s right to see the film it wants. With the State machinery and the judiciary also going by the dictates of these political forces (or mobs), the film maker’s autonomy and his constitutional right of free expression become fictional.

History of Mob Justice

In his paper on Bollywood’s travails, Vishal Langthasa recounts cases of mob justice and State interference since 2006. In 2006, Fanaa was banned in Gujarat because the film’s hero, Amir Khan, had spoken against the forced removal of tribals and peasants by the Narmada River dam project in that State. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government in Gujarat, which was backing the project, felt that the matinee idol’s support for the protest would strengthen the protest. In 2007, Gujarat banned Parzania because it was about a Parsi boy who went missing during the infamous 2002 anti-Muslim riots in BJP-ruled Gujarat. The film went on to bag the National Best Film and Best Actress awards. Aaja Naachle was banned in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab because the film had a song which had a line saying: “a cobbler tries to become a goldsmith” which was deemed a slur against the cobbler caste, deemed “lower” in the Hindu social hierarchy than goldsmiths.

Anurag Kashyap’s Black Friday a film on the serial bomb blasts in Mumbai, was banned nation-wide in 2005 because it named names. But the ban was lifted in 2007 following a court order. In 2008, Jodha-Akbar was banned in several North Indian States because the Rajput or Kshatriya community accused the film producer of making Jodha, a Hindu Rajput princess, the wife of the Muslim emperor Akbar. Eventually, the Supreme Court stayed the ban on the film in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Uttarakhand. The ban in Madhya Pradesh was lifted by the High Court. Eventually Jodha Akbar proved to be a hit.

Deshdrohi a film on the way migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh were being exploited in Maharashtra was banned at the instance of the Maharashtra Navanirman Sena (MNS) as it showed Maharashtra State in bad light. The film Padmavat came to the point of being banned as it showed a Muslim King Allauddin Khilji pining for a Hindu-Rajput princess, Padmavati.

Bollywood, as the Hindi film industry is called, had been very secular in the past and had provided space for cross-cultural interaction and integration. But this is under threat now. Themes conducive to the promotion of community-based nationalism are being used repeatedly, largely to the advantage of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s Hindutwa policy. Pritish Nandy, writing in the New York Times pointed out that “some Bollywood actors and producers have cozied up to the Hindu nationalist establishment.”

Referring to the on-going controversy surrounding the death of young Bollywood star, Sushant Singh Rajput, and the alleged racketeering in drugs there, Nandy said: “The Hindu nationalists are hoping this sudden and unexpected assault on Bollywood will force the film industry into complete submission to a government keen on wiping out dissent and liberal ideas. They want Bollywood at their command, an accessory to furthering their exclusivist, majoritarian politics.”

He pointed out that there was “a method to the madness’. The suicide of star Sushant Singh Rajput from Bihar in North India was turned into a murder by the pro-BJP mainstream media and social media and accusing fingers were pointed against an alleged drug mafia comprising stars from outside the Hindi-speaking belt like Deepika Padukone from Karnataka and Rhea Chakraborty from West Bengal.

“Rajput’s native state of Bihar, which sends 40 representatives to the Indian Parliament, is scheduled for state elections in October. Mr. Modi’s B.J.P., hoping to strengthen its grip on power in Bihar, positioned itself as fighting for justice for a son of the soil who was murdered,” Nandy said. He pointed to a BJP election poster in Bihar which said: “We haven’t forgotten. We won’t let you forget,” with the party’s electoral symbol and Rajput’s smiling face on it.

Nandy further states that “a study of online behavior by the University of Michigan concluded that conspiracy theories suggesting that Mr. Rajput was murdered were amplified by members the ruling B.J.P. and the TV networks that operate as extensions of the Hindu nationalist establishment. Leaders and allies of the B.J.P. supported a demand by the deceased actor’s family that a federal agency probe his death.”

Spearheading the Hindutwa lobby in Bollywood now is Kangana Ranaut. She is now facing a police case for allegedly fomenting Hindu-Muslim conflict in Bollywood.