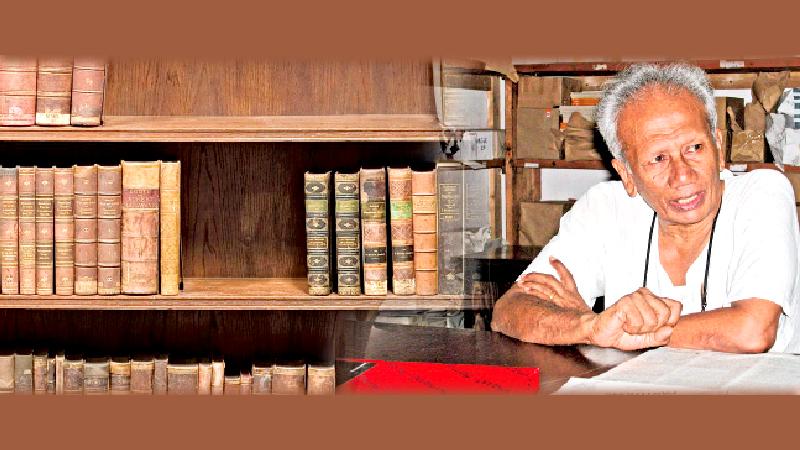

Dr. Ranga Wickramasinghe, the youngest son of pioneering Sinhala writer Martin Wickramasinghe, is preparing to launch his new English translation of Viragaya (Devoid of Passion), the best realistic novel in Sinhala as regarded by most critics. Earlier, he had translated Martin Wickramasinghe’s short story collection titled Selected Short Stories which won the state literary prize for the best English translation in 2008 and also co-translated Martin Wickramasinghe’s trilogy, Gamperaliya (Uprooted), Kaliyugaya (The Age of Kali) and Yuganthaya (Destiny). The Sunday Observer met him to discuss his translation work and memories of his father.

Q: You are now ready to publish the English translation of Viragaya by your father?

Q: You are now ready to publish the English translation of Viragaya by your father?

A: Yes, I’ve just finished the English translation of Viragaya. Earlier, it was translated by Prof. Ashley Halpe, but I’m not satisfied with that as there are many inaccuracies. So, I began to translate it some time ago, and now, it has been finished.

Q: You have translated over four books by Martin Wickramasinghe into English and you have also written your own stories?

A: I have written two short stories. Somebody had asked my father to tell me to write something for the paper. Then, my father told me to write a story. At the time, I was twelve years old. I had written a short story for my pleasure.

It was Shatha Dahaya (Two Cents). I showed it to my father. After reading it, he said “It’s good! It was published in the Silumina some days later. That’s how my first story was published.

Q: Did your father encourage you to write?

A: He encouraged me to get what I write published, but never persuaded me to become a writer.

Q: Why didn’t you publish a short story collection with these stories?

A: I didn’t write enough stories to compile a book. I couldn’t find time to write fiction with my medical studies and thereafter, with my medical profession. But I wrote about my father.

Q: Your elder sister Rupa Saparamadu also had literary talents, but didn’t publish?

A: She also wrote about our father, but didn’t write stories. Later, she got involved with her business. They had a Publishing house and then she became a hotelier.

Q: Your father had a personal library. Could you recall about it?

A: When he was at home, he was always engaged in his studies which included the library. I remember that library since we lived at Mount Lavinia, because I used to read from his library. He had many illustrated books on various subjects, such as astronomy, anthropology and biology. All of them he got from abroad. I got interest in reading because of his books. I don’t think that even some of our scientists had read like him on scientific subjects.

Q: Was Martin Wickramasingne a fast reader?

A: He hadn’t any exceptional gift in reading fast, but when he started reading, nothing distracted him. There were six children in our house. We were fighting and shouting, but it didn’t bother him at all. He could read in any noisy place. I never heard him ask my mother to stop making us noise or anything. He didn’t even close the doors of his study room when we were shouting.

Q: Did he use any other library?

A: He had no need to go to other libraries as he had a huge book collection. He used to collect books rather than borrowing books. However, he went to Colombo Public library.

Q: In his autobiography Upan Daa Sita (Since I was born), he relates an interesting incident he experienced in a bookshop?

A: On pay day, he used to go to bookshops, such as Caves, Apothecary which were major bookshops in the country. When he went there, he used to spend a couple of hours looking through books. But one day, one of the bookshop owners – he is an Englishman – told him, “I know you come here a couple of days for a month. You buy one book after looking through many books. I don’t mind it. But please don’t do this! – He showed my father how he was of the habit of thumbing the pages of the book after touching his tongue and thereby coming into contact with saliva.

Q: You gave away your father’s personal library to the Colombo National Library a few years ago?

A: Yes, we gave away his personal library consisting of 6,000 volumes to the National Library except for a few books.

Q: In Upan Daa Sita, he regrets his expenditure on books instead of sending money to his mother who was undergoing financial hardships?

A: When someone recalled about his mother, he said, “My mother was very foolish. There were days she had gone without food, but she never informed me about her hardships. My grandmother had seven daughters. By the time all of them given in marriage, she had hardly anything of her own. My father later learnt from people that she was practically destitute in her final years. She had no money at all. As father was in Colombo, he wasn’t aware of this. Grandmother was alone living with one of her daughters in Mahagedara, Koggala.

Most daughters were also poor because their husbands sold their properties. Though they were from wealthy families, they became destitute eventually. When I was 18, I asked father about grandmother’s plight. He said his sisters had been ordered by his mother not to write a word about their difficulties to him. He always regretted about his mother. Once I saw tears coming down from his eyes remembering his mother. That was the only time that I saw him crying.

Q: Have you seen similarities between Nanda, one of the main characters in Gamperaliya and your father’s sisters?

A: Yes, my father created the characters Nanda and Anula by them. Nanda was more closed to the aunt Nellie who was bit of a playful type.

Q: How often had your father been to his home at Koggala?

A: He went to Koggala Mahagedara once a year or twice a year. He would always take us to Koggala during the April Sinhala Avurudu holidays. My maternal grandmother had also been looking forward to receiving us. We travelled by train. When we got down from the Ahangama railway station, a buggy cart sent by grandmother was waiting for us to fetch us to Koggala. My father sometimes had to leave for Colombo within a few days when we were staying there because he had such a busy journalistic career. However, it was a very good time for us during the April holidays, especially because we had a lot of relatives and places to visit there. When father was with us in Koggala, he sometimes accompanied us to the beach where he loved to go.

Q: Had he visited his friends at Koggala?

A: Yes, most of the time his friends were older than him. In the Upan Daa Sita, he described an incident he and his friend Oibert Silva faced during the Sinhala – Muslim riots in 1915. They travelled to Weligama during the curfew with swords, iron bars and other weapons in the buggy cart with other youth and came back without any harm just by chance.

Q: Was your father a religious person?

A: He went to temple and participated in religious observances, but not regularly. I saw him go to temple on Poya days.

Q: You said you saw him crying only once. Was he in a happy mood?

A: Yes, he was always in a happy mood. Only thing he was worried about when we were young was about my eldest brother Sarath Kusum Wickramasinghe because he was bit riotous in school. He misbehaved there and the principal threatened to expel him from school. Actually, he was the brightest of our family and later, he became the Chairman of CIC and some of the big companies in the country – Two years ago, he passed away. However, father somewhat bothered about him. Other than that, he was in a happy mood.

Q: When the novel Bhawa Tharanaya was relesed, there was a huge uproar against him?

A: I remember some writers told my father to apologise for some of the details in the novel in its new prints. But my father just laughed and ignored them. One of the journalists wrote that my father should be jailed after filing a case in court. But my father only laughed at such reactions. When the negative reaction was at a peak, he said that many materials in the book he took from Amawathura, a classical Sinhala prose.

Q: When Martin Wickramasinghe became blind during the final years of his life, it would have affected him badly?

A: Yes, because he couldn’t read after that. But he never gave in. He used magnifying glasses to read. I facilitated him with an enlarged TV screen so that he could read big letters – the text of the book was projected to the TV screen in large letters. But later in his life, that devise also didn’t work for him.

He couldn’t make out the words. However, he could select the book he wanted from his library despite blindness. Dayapala Jayanetthi, who is our senior staffer in the Martin Wickramasinghe Foundation, has described how my father asked him to select a book from the bookshelves without seeing the shelves.

The my father could say correctly in what shelf and in which row each book was with his blindness.

When it was difficult for him to find books, I told him to classify the books like in a library. The other reason was that many books started to disappear, because some people, who came to see my father, picked out some books and walked away. So I catalogued them giving each book a number in an order – when someone noticed a number for each book, they beware of stealing books.

Q: Was your father colour blind?

A: Yes, to him, many colours were much the same. It was a genetically inherited problem for him. When my mother asked him to bring her a sari of a particular colour, he always misjudged it for an odd colour one.

Q: Could you remember his readings when he was confined to bed?

A: He asked someone close to him to read this and that passage of a book for him. While that person was reading it aloud, he listened to it.