This week we look at certain areas of the medical heritage of the Sinhalese (Deshiya Chikitsa) that was connected with vocations practised in ancient society such as those connected with fire, forests/trees and traditional martial arts used by the military of the Lankan kings.

To understand how our medical systems were associated with different vocations and to comprehend as a nation the importance of resurrecting and conserving our medical heritage, we feature below an interview with senior Cultural Anthropologist and Traditional Knowledge/Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH)/Ayurveda specialist Dr. Danister Perera. Dr. Perera teaches Indigenous Knowledge in Natural Resource Management at the University of Sri Jayewardenepura and Sri Lankan Culture in Sociology at the University of Kelaniya. Dr. Perera is a member of the UNESCO national steering committee of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH).

In this interview he notes the high endemicity in biodiversity which was linked to the survival of our ancient medical traditions aided also by the support given by ancient kings to preserve and promote the country’s medical systems. He highlights that urgent initiatives are needed to rescue some of our ancient medical systems from devastation.

We feature below the excerpts of the interview with Dr. Danister Perera.

Q: As a cultural anthropologist, indigenous knowledge and Ayurveda expert could you comment on the ancient branches of medicine of the Sinhalese connected with traditional vocations that date back to the time of Sinhalese Kings?

A. The Sinhalese were very knowledgeable in practical medicine and their medicinal treasure trove was the forest as noted by Robert Knox who recorded facts from his experience of living with ancient Lankans for 19 years. This is a very authentic and precise statement gathered through the real living heritage of then society. But it is very clear that historically after European invasions Sinhalese medical lore was undergoing a declining phase due to the low esteem and lack of government support. Therefore this is a good indicator to understand the importance and due respect given by royal patronage to the indigenous medical practice. It is only because of this patronage and consistent support that it survived at that time. This is a point that we should note as all of us as citizens hold the responsibility for the survival of our medical heritage.

What we refer to as Ethnomedical systems of Sri Lanka is the medical system that existed connected to the mainstream medical tradition employed in the then national healthcare system (Deshiya Chikitsa/Lankan Ayurveda). This ethnomedical system was a village based local tradition that was associated with people’s livelihoods. These ethnomedical practices that prevailed within the ancestral wisdom had been utilised in diverse manners according to the people’s day to day health needs and local community livelihoods. Similarly as indigenous medicine, traditional livelihoods also cannot be separated from a country’s culture and natural environment. Ancestral heritage of medical lore originated from the hunter-gatherer era and developed throughout the farming civilization compatible with all livelihoods.

Q: What are the areas of indigenous medicine (Deshiya Chikitsa) that fall under ethno medical traditions associated with some of the ancient crafts/vocations practised in ancient Sri Lanka? Could you explain in detail highlighting the anthropological significance?

A. We had the traditional martial arts associated medical traditions. After the British outlawed the Angam fighting it struggled to survive and survived in two areas; as a medical system (used to heal nerve points of the body which are affected usually in fighting) and Angam also was directed to traditional dance where some of the steps associated in fighter movements were included in dance form.

Ancient Lanka also had the traditional burn treatments that has significant efficacy but not widely practiced today among the new generation of those in indigenous medicine. This burn treatment was believed to have originated from blacksmith families who were usually dealing with fire and facing burns in their routine work. They had their own treatments for burns.

Also the fire dancers who perform in annual Buddhist pageants also have these kinds of medicines used for their burns. Another local tradition of medicine was that which was associated with those who deal with forests/trees etc., and known in Sinhalese as gas wedakama.Generally this was for those who fall from trees and associated with livelihoods such as toddy tapping. Also snakebite treatments were very much practically used by several traditional medicine lineages and the Gypsy people. This is how ethno-medical traditions evolved within the context of livelihoods.

Q: Of these could you detail out the branch of medicine that were practiced by the Angam fighters of yore who were affiliated with different kings.

A. I am not familiar with angam fighter traditions in ancient kingdoms but ancient records such as Mahavamsa and other chronicles precisely mention about medical interventions associated with millitary operations in ancient times. Overall, our ancient medical science played a very crucial role in physical fitness of soldiers and security guards employed by the kings.

According to information on ancient millitary medicine in Sri Lanka as recorded in our chronicles as Mahavamsa and other historical sources such as inscriptions it was mandatory to employ physicians and surgeons in a war-field to take care of soldiers and their casualities. According to some sources even the elephants and horses used in war were treated by indigenous medical practitioners.

The best example comes from Mahavamsa about the elephant Kadol that was injured by boiling oils and metal liquids poured by enemies during the Vijitapura battle. The elephant was given an instant treatment by Vetenary physicians to the extent that it was able to attend battle next day in good health. In the battle with the Burmese King, the Sinhalese army in the 12th century was attacked with poison arrows on Burmese soil and the wounds became highly septic but were sucessfully attended to by the physicians attached to army. Therefore it is a fact that our ancient millitary medical interventions were timely applicable and successful.

Q: So there were specialised physicians only to treat fighters of the kings?

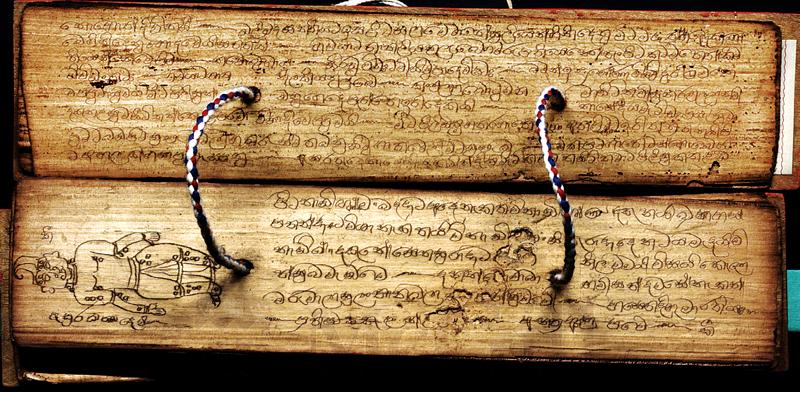

A. Certainly there were. Most of the kings had their own royal physicians and a group of medicial experts for treating royal family and other elites. Similary there were physicians employed for treating soldiers and special fighters. According to some sources written in palm-leaf manuscripts there were special formulations that were inherited by certain families where the making of the relevant medicines involved a knowledge process that was kept staunch secret.

Q: Could you explain more about the Nila Wedakama and its link to traditional martial arts?

A. Mostly the fighters used some vital points for harming the enemy in fighting. These vital nerve points were also used in treating ailments caused by trauma which fall to the category of psychiatry/psychology related ailments. Therefore some believe that the Nila Wedakama is evolved from this angam tradition. Nila Wedakama has different versions that are applied with other medical specialities too. In addition to trigger point therapy, vital nerve points are punctured and burnt to control chronic pain and neuromuscular disorders.

Q: So the type of medicines you describe fall into the category of what we identify in common parlance as Sinhala Wedakama or as earlier known Deshiya Chikitsa?

A. As we know Sri Lanka had a high endemicity in biodiversity of which most of crucial medicines were embedded. Also the Sinhalese culture prevailed for centuries nurtured with Buddhism as an integral part of medical practice. These two features were combined together to create the vital identity of the Deshiya Chikitsa tradition.

Q: There are still many practitioners from traditional medicine family lineages. Some of them may not know the 100% authentic treatments as practiced thousands of years ago but the traditions and the emotional connection to it still survive. There are also new generations showing great interest in understanding and studying these systems. Don’t you think we should as a nation assist in the survival of this heritage and if possible use existing ancient data on Ola leaves etc., to revive them?

A. Yes. We must have a national policy and a strategic plan to revive and facilitate these vanishing traditions. Once we tried to submit a proposal to nominate this vidum pilissum tradition for the urgent safeguard list under the UNESCO 2003 ICH convention but could not succeed due to the death of the last practitioner. It was a tragedy that most of our exclusive but lesser known and rarely practiced traditions are threatened. Urgent initiatives are needed to rescue them from devastation.

Q: Pertaining to traditional medical treatments for burns could you explain how these compares to Western cures?

A. Yes. There is a special indigenous medical branch for treatments of burns which is highly effective and succesful. In western medicine most of critically burnt pateints are managed in intensive care units and they use antibiotics to prevent secondary infection while controlling the liquid balance in the body. Unfortunately most of the patients recover with many deformities and complications. But we have seen many such cases are sucessfully managed by our physicians through indigenous medicine and patients recover with minimum complications.

Normal burns are cured even without a scar with idigenous medicine. But we must advice the public to always choose a qualified and authentic indigenous medical practitioner who have a reputation of such successful interventions. My suggestion is to carry out some research and case study series on the successfulness of such medical interventions and publish them for academic review. Eventually best practices can be integtrated into the mainstream systmem and create practice protocols for the betterment of general public.

Q: Could you comment on the World Health Organisation (WHO) and its acceptance of traditional medicine of the world?

A. WHO’s policy is very clear on traditional medicine and published from 1978 but unfortunately neglected and partly ignored by Sri Lanka from the begining. The Alma Ata declaration in 1978 was a historical landmark of WHO’s attitude on traditional medicine and gave a recommendation to incorperate traditional medicine into the primary healthcare in member countries. From that event WHO has published many techincal reports, survey reports, colloborative recommendations and guiding documents for the progressive initiatives to be followed by the governments. In 2002-2005 the WHO traditional medicine strategy provided recommendations on quality, safety and rational use of traditional medicine and encouraged the governments to formulate policies and legislations with regard to that.

The next most important landmark initiative was the Beijing declaration made in 2008 extactly three decades after the Alma Ata. According to this declaration traditional medicine should be respected, preserved, promoted and communicated widely and appropriately based on the circumstances in each country. Recognising the progress of many governments to date in integrating traditional medicine into their national health systems is clearly highlighted. The WHO has emphasized the importance of accreditation or licensing of traditional medicine practitioners and encouraging the communication between conventional and traditional medicine.

In the recent history WHO introduced the Ten year traditional medicine strategy 2014-2023 of which we come to the end of term in next three years doing nothing with zero outcome. I believe that WHO has a mandate to propagate traditional medicine with the intention of creating a people friendly and cost-effective healthcare system that provides a economically viable services to the general public. Sri Lanka as a country with a great heritage of indigenous medical wisdom and natural resources rich in medicinal properties must ensure it uses its potential in contributing to the national economy in a sustainable manner.

Q: In this pandemic era there is in general a subtle notion that WHO will only nod their head to Allopathy for the treatment of the virus (despite the well known fact as asserted by the WHO that there is still no Allopathic cure for the virus). Could you explain this sociologically and anthropologically studied from a post Colonial lens?

A. Even though WHO has allowed to carry out clinical trials to test some herbal medicines in the African region for Covid-19 our biomedical monopoly still do not accept the validity of traditional medicine in this pandemic. This is very similar to John Davy’s attitude in 1921 as he expressed in a very disgraceful manner “Sinhalese medicine is built up on a system of their own, founded on the fancy, and equally complicated and erroneous”. We must not forget that our history has revealed the great tradition of ancient hospitals and healthcare system operated from pre-Christian era. Just as Chinese traditional medicine has been successfully integrated in controlling Covid-19 when comparing to Europe and US, we also can produce the same results by combating pandemic with our own medicine.

Q: There are reportedly many cases where traditional physicians are giving curative and preventive treatment pertaining to Covid very successfully but yet due recognition does not seem to be going to these physicians. Your comments?

A. In this context we must be very careful to identify the genuine indigenous practitioners who claim that they have successfully treated Covid-19 cases. Some of the social media and youtube propaganda have fake products and are cheating people in this matter. But personally, I know there are several practitioners who have treated even foreign Covid-19 patients who were with serious symptoms and made them recover in short period with PCR negative results.

It is not fair to refuse their formula without proper testing or experimenting to validate the outcomes. In some Western nations they have started integrating traditional treatments for Covid-19 patients and getting more successful results but these are not yet officially recognised.

We must call for a national agreement with traditional physicians/Ayurveda doctors, scholars, intellectuals and academics to involve in the planning and implementation of the Covid-19 recovery program with an integrated approach.

Q: On WHO wanting clinical trials on traditional medicines used for hundreds of centuries, don’t you think it ironic, given that old civilisations have perfected these long before the West ?

A. WHO is not asking for clinical trials on ancient medicinal formula when it is used for the similar condition as claimed in the formula. But when it is tested for a new conditions recognition is always based on trials to prove the efficacy.

For safety means there is no need to go through toxicity testing but human trials can be carried out based on case studies. In all pros cons we need to adhere to global standards to reach a win-win situation.