The 1928 Summer Olympic Games, officially known as the Games of the IX Olympiad, was celebrated in an atmosphere of peace and harmony from July 28 to August 12, 1928 in Amsterdam, Netherlands. These Games were a tremendous success and contributed to the ever-increasing attraction of the Olympic Games.

A total of 46 nations were represented at Amsterdam. Malta, Panama and Zimbabwe competed at the Olympic Games for the first time. Germany returned to the Olympic Games for the first time since 1912, after being banned from the 1920 and 1924 Games. A total of 2,883 athletes – 277 women and 2,606 men took part in the Games.

Host City Selection for 1928

Dutch nobleman Frederik van Tuyll van Serooskerken first proposed Amsterdam as host city for the Summer Olympic Games in 1912, even before the Netherlands Olympic Committee was established. The Olympic Games were cancelled in 1916 due to World War I. In 1919, the Netherlands Olympic Committee abandoned the proposal of Amsterdam in favor of their support for the nomination of Antwerp as host city for the 1920 Summer Olympics.

In 1921, Paris was selected for the 1924 Summer Olympics on the condition that the 1928 Summer Olympics would be organized in Amsterdam. This decision, supported by the Netherlands Olympic Committee, was announced by the IOC on June 2, 1921. The only other candidate city for the 1928 Olympics was Los Angeles, which would eventually be selected to host the Olympics four years later.

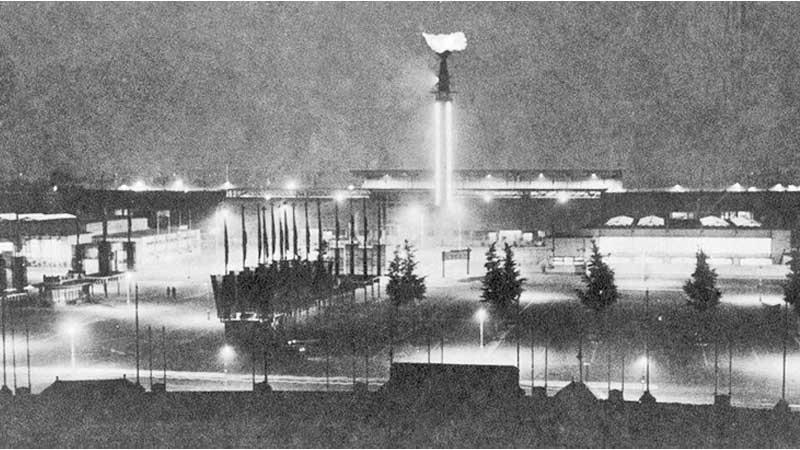

Opening Ceremony

The Games were officially opened by Prince Hendrik, consort of Queen Wilhelmina, who had authorized her husband to deputize for her. The Queen was unable to attend the opening ceremony as she was on holiday in Norway and did not want to disrupt her trip. This was the second time a Head of State had not personally officiated at an Olympic Opening Ceremony. The first being St. Louis 1904, which were officially opened by David R. Francis, the Mayor of St. Louis.

The Queen had initially refused to make an appearance at either the opening or closing ceremony; it is thought that she objected to the Netherlands hosting the 1928 Games as she considered the Olympics to be a demonstration of paganism. However, she returned from Norway before the conclusion of the Games, to be present at the Closing Ceremony, and she presented the first prizes at the prize distribution which was held immediately beforehand. These were the first Olympic Games to be organized under the IOC President, Henri de Baillet-Latour.

Olympic Firsts at Amsterdam 1928

It was for the first time, a symbolic ‘Olympic Flame’ was lit during the Games. The cauldron designed by a celebrated Dutch architect, Jan Wils was placed at the top of a tower inside the stadium for the duration of the Olympics, a tradition that continues to this day.

Also, for the first time the ‘Parade of Nations’ was led by Greece, in recognition of their role in Olympic history, and Holland, the hosts, marched in the last. Greece first, hosts last would become a permanent part of the Olympic protocol since 1928.

These Games also attracted Coca-Cola as a sponsor, who organized a freighter to deliver the United States team and 1,000 cases of drinks to Holland. The relationship between the IOC and Coca-Cola continues until this day. Athletics events were held on the first standardized track of 400m built on reclaimed land.

These Games were the first to bear the name “Summer Olympic Games,” to distinguish them from the Winter Olympic Games. These Games were the first to feature a fixed schedule of sixteen days, which is followed since then. In previous Olympics, competition had been stretched out over several months.

Besides, for the first time, women competed in gymnastics and athletics. The number of female competitors more than doubled as women were finally allowed to compete and Asian athletes won gold medals for the first time. The 800m for women was marred when most of the competitors finished in a state of exhaustion and women were not allowed to run again until 1960.

Many cars were expected for the Games, but Amsterdam had no more than 2,000 single car parking spaces. Consequently, a few new parking sites were provided, and a special parking symbol was launched to show foreign visitors where they could park. The white P on a blue background was to become the international traffic sign for parking, which is still used today.

Athlete and Sports Highlights

During the 1928 Summer Olympic Games, there were 14 sports, 20 disciplines and 109 events. Women’s athletics and team gymnastics debuted. Five women’s athletics events were added: 100m, 800m, high jump, discus throw and 400m hurdles.

Paavo Nurmi of Finland won his ninth, and final, gold medal in 10,000 m. Canadian Percy Williams exceeded expectations by winning the sprint double of 100m and 200m. Boughera El Ouafi of France won the gold in Marathon. Mikio Oda of Japan won triple jump with 15.21 becoming the first gold medalist from an Asian country. Pat O’Callaghan of Ireland, took the gold in Hammer Throw.

Halina Konopacka of Poland became the first female Olympic track and field champion. Reports that women’s 800m run ended with several of the competitors being completely exhausted were extensively and inaccurately circulated. As a result, the IOC decided that women were too frail for long-distance running, and women’s Olympic running events were limited to 200m until the 1960s.

Crown Prince Olav, who would later become King of Norway won a gold in 6 meter sailing event. Uruguay retained its title by defeating Argentina in football. Kaatsen, Korfball and Lacrosse were demonstration sports. These Games also included art competitions in five categories: architecture, painting, sculpture, literature and poetry.

Farewell Games of Nurmi and Ritola

In the 1920s success in the long-distance events was the sole preserve of the Finns. At the forefront of that success was the inimitable Paavo Nurmi, whose record of 9 golds stood for 80 years until American swimmer Michael Phelps finally broke it in 2008.

Legendary Paavo Johannes Nurmi (June 13, 1897 – October 2, 1973), called the “Flying Finn” or the “Phantom Finn”, won 9 gold and 3 silver medals in the Summer Olympic Games. Vilho “Ville” Eino Ritola (January 18, 1896 – April 24, 1982) also known as one of the “Flying Finns,” won 5 gold and 3 silver medals. It says everything about the balance power in the distance running at Amsterdam.

Four of the nine finalists in 3,000m steeplechase were from Finland. Led by Nurmi, Finnish runners were the dominant force and he was expected to add to his bulging haul of gold.

Nurmi had won 5 gold medals at Paris 1924 but was absent from 10,000m after Finnish officials said he was competing in too many events. However, in Amsterdam he opened his campaign by winning 10,000m in an Olympic record.

Ritola had to long live in the shadow of his legendary countryman. He unfortunately played second fiddle during one of the greatest dynasties Olympic track and field has ever witnessed. Ritola also had a commanding Olympic record; at Paris 1924, he won 4 gold and 2 silver medals, and his tally would have been better but for the ever-present Nurmi.

Four years later and again the medals were expected to be shared between the two teammates. Nurmi won his ninth and last gold medal in a scintillating 10,000m with Ritola clinging on until a burst down the home straight sent Nurmi past the tape about two metres clear.

Four years later and again the medals were expected to be shared between the two teammates. Nurmi won his ninth and last gold medal in a scintillating 10,000m with Ritola clinging on until a burst down the home straight sent Nurmi past the tape about two metres clear.

Then in 5000m, Ritola was eager for revenge and it proved to be a highly tactical race in front of a packed, expectant crowd at the Olympic Stadium. Nurmi upped the pace at halfway and most of the field were lagging badly. Ritola and Swede Edvin Wide kept up with the Finn and as the event entered the final 400m.

With Ritola at the front, his head ducking inside to catch a glimpse of Nurmi on his shoulder, the decisive break came with 150m to go. Ritola burst clear and Nurmi immediately glanced back to ensure his silver was safe knowing his countryman’s burst of speed had put the gold beyond him.

Loukola’s Gold in Steeplechase

When the heats of the steeplechase came around, Nurmi was again expected to prevail but a spectacular fall nearly put paid to his chances. He was helped up from his fall by Lucien Duquesne and in return Nurmi paced the remainder of the race to help the Frenchman qualify.

Team-mate Toivo Loukola, who had once been declared unfit for military service by the Finnish Army because of breathing problems, qualified some 20 sec faster than Nurmi and lined up with a cavalry charge of Finnish teammates.

He controlled the race from the very beginning and although Nurmi kept in touch for much of the race he applied the pressure in the closing 800m – often taking off and landing on the same foot. His time of 9:21.8 was a new world record, finishing some 10 sec clear of Nurmi and Over Andersen who completed a Finnish clean sweep in third.

The First Lady of Olympic Track

American sprinter Betty Robinson was the first women’s 100m champion. She remains to this day the youngest and her story is one of the most remarkable in the annals of the Games. When she ran in the final of 100m, it was only her fourth competitive race and she was just 16. She had been spotted running after a train by her schoolteacher and was encouraged to take up sprinting.

She arrived in Amsterdam about as inexperienced as you can be but sometimes that level of naivety can work in your favour, and Robinson was far from over-awed by the occasion. The six-woman final was whittled down to four sprinters after a series of false starts saw two competitors disqualified. When the start finally came, Robinson surged steadily clear before winning in a world record of 12.2.

Three years later, Robinson was to experience even greater drama. Travelling in a biplane piloted by her cousin, it crashed, and Robinson was given up for dead when rescuers found the body among the wreckage. She and her cousin were placed in the trunk of a car and taken to an undertaker but on arrival they were found to be alive and Robinson remained in a coma for seven months.

She had suffered a broken leg, a crushed arm and severe concussion but her determination saw her recover and by 1936 she was back at the Olympics in Berlin. So severe was her leg injury that she was unable to kneel and could not compete in 100m. However, she was still able to run in the relay and help the US quartet to win 4x100m gold in an astonishing performance.

Kings Supremacy in High Jump

The now universal ‘Fosbury Flop,’ perfected to great success at Mexico City 1968, was many decades away and the jumpers in Holland used a variety of spectacular techniques to clear the bar. Many used an elaborate scissor-kick style, which required a remarkable piece of athleticism and agility to clear the formidable heights.

American Bob King had a technique all his own. He had had a glittering collegiate career and led a strong American field event contingent in Amsterdam. Expectation was high with all but one of the previously contested high jump gold medals going to American athletes. 35 athletes vied at the qualifying round.

In the finals, when the bar reached 1.91 and only five athletes made successful clearances. King and two American team-mates succeeded. While his rivals persisted with the traditional scissor kick, King’s technique gave him the edge. He ran in at an angle, raising his right leg level with the bar before tucking his left underneath. With the bar raised to 1.94m, King recorded the only successful clearance but not until the bar performed a nerve-jangling wobble after the American clipped it with his trailing leg.

Dominance of Americans in Pole Vault

The men’s Pole Vault at Amsterdam 1928 was less of a guessing game about which nation would provide the winner, more a matter of which American would claim the ultimate glory. They completely dominated the competition. Sabin Carr and Lee Barnes, the winner of Paris 1924 gold had spent the previous 12 months exchanging the world record.

It was on a rainy afternoon in Holland that they both comfortably cleared the qualifying mark of 12 feet. The elements did not favour them. A strong, gusting wind and heavy rain made the run-up and landing equally treacherous. However, Carr known for his feats under trying conditions won the gold. He set a new Olympic record of 13ft 7 inches to continue the Americans’ dominance in the field events after the poor showing of their athletes on the track.

Kuck’s Record Breaking Shot at Glory

Throughout his school life, John Kuck was the most prodigious of field athletes, breaking a multitude of records in all throwing disciplines. Blessed with an agile frame and lightning bursts of speed, Kuck was among the favourites, yet a broken ankle threatened to derail his chances before the competition even started. As a student, he broke the world record in shot put and javelin and after a distinguished athletics career which saw him break more than 100 records and the Amsterdam Games were very much seen as a swansong.

He and the German thrower Emile Hirschfeld, who claimed a new world record of his own just a couple of months before the Games commenced, were the warm favourites for gold when the competition started. In the qualifying round at the Olympic Stadium his ankle injury was clear for all to see and he carefully threw the bare minimum to ensure his place in the six-man final. His US colleague, Herman Brix who would later become a prolific film actor, broke the Olympic record in qualifying.

In the finals, all the competitors were at the peak of their form. Using a more side-on throwing style to their modern-day equivalents, the standard was high. It was clear a throw near or better than Hirschfeld’s best mark of 15.79 would be required to take the gold. The pain from his ankle injury set to one side, Kuck sent the shot out to a new world record mark of 15.87.

Winning Streaks and Notable Events

The team India swept to victory in field hockey. Between 1928 and 1956, India’s men would win six straight gold medals in this event. Another winning streak also began in 1928, when Hungary earned the first of seven consecutive gold medals in team sabre fencing.

The actions of Australian rower Henry Pearce at Amsterdam have since become legend. He stopped midway through his quarter final to let a family of ducks’ pass, but still went on to win the race and eventually the gold medal.

The United States emerged victorious with 22 gold, 18 silver, 16 bronze - total of 56 medals; Germany came second with 10G, 7S, 14B, totaling 31; Finland won 8G, 8S, 9B - a total of 25; Sweden, Italy and Switzerland won 7 gold medals each whilst France and the host Netherlands secured 6 gold medals each.

It was the third consecutive Summer Olympics Games that the United States won the highest medals, fulfilling the target set by the President, United States Olympic Committee, General Douglas MacArthur. Then, the youngest 2-star General of the United States Army, he claimed in Amsterdam, “We are here to represent the greatest country on earth. We did not come here to lose gracefully. We came here to win decisively.”

(The author highlights spectrum of sports extravaganza. He is the winner of Presidential Academic Award for Sports in 2017 and 2018 and recipient of National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc)