If Martin Wickramasinghe is considered to be ‘father of Sinhala fiction’, Piyadasa Sirisena should be considered the ‘grandfather of Sinhala fiction’, because without him Wickramasinghe may not have been able to create the first realistic Sinhala novel, Gamperaliya, so early. Piyadasa Sirisena was the first writer who developed vast readership around the Sinhala novel - his first novel Vasanavantha Vivahaya Hewath Jayatissa Saha Roslin (Lucky marriage or Jayatissa and Roslin) sold 25,000 copies within 10 years. However, until very recently the academia in Sri Lanka took him for granted as a writer. One reason for it that Professor

Ediriweera Sarachchandra demerited his fiction. But he is a writer who deserves to be close study. Piyadasa Sirisena’s 146 birth anniversary fell on last August 31 and we think it is an ideal time to discuss his literary life.

Ediriweera Sarachchandra demerited his fiction. But he is a writer who deserves to be close study. Piyadasa Sirisena’s 146 birth anniversary fell on last August 31 and we think it is an ideal time to discuss his literary life.

Early life

Starting from the beginning, Piyadasa Sirisena was born on August 31, 1875 in the village of Athuruwella, Induruwa in Galle district. His name at birth was Pedrick de Silva, and he was the last child of five in his family. There are three schools that he took his early education which were Warahena school, Induruwa, Bentara school of Bentota and Brohier’s school at Aluthgama, a missionary school where he learned English.

From childhood he developed an interest towards literature and started to write to newspapers. Meanwhile, he had a great admiration for the nationalistic movement of Anagarika Dharmapala which resulted in changing his name from Pedrick de Silva to Piyadasa Sirisena. At the age of 18 he wrote his first book, a volume of poetry, titled Ovadan Mutuvela. Two years later, when he finished his school education, he came to Colombo in search of employment, there he published the book. Then, he joined in ‘Sarasavi Sandaresa’ as a journalist and started to write his first novel, Vasanavantha Vivahaya Hewath Jayatissa Saha Roslin which was published in installments in the ‘Sarasavi Sandaresa’ newspaper.

In 1905, ‘Sinhala Jathiya’, a daily newspaper was inaugurated and he became its editor. As he was an ardent follower of Anagarika Dharmapala he made use of ‘Sinhala Jathiya’ as a medium for spreading his nationalistic, anti-colonial thoughts. In fact, he became the literary voice of Anagarika Dharmapala. The following passage from one of his editorials at ‘Sinhala Jathiya’ attests to this fact:

In 1905, ‘Sinhala Jathiya’, a daily newspaper was inaugurated and he became its editor. As he was an ardent follower of Anagarika Dharmapala he made use of ‘Sinhala Jathiya’ as a medium for spreading his nationalistic, anti-colonial thoughts. In fact, he became the literary voice of Anagarika Dharmapala. The following passage from one of his editorials at ‘Sinhala Jathiya’ attests to this fact:

“As long as the Sinhalese are feeble and splintered into diverse castes, they will not gain modern knowledge. As long as they do not gain modern knowledge, they will be unable to eliminate groundless fears and a feeling of inferiority. As long as this sense of inferiority prevails, the Sinhala people will not be wealthy and strong.” (Sinhala Novel and the Public Sphere, Wimal Dissanayake, pp 119)

Is this the kind of sentiment that Anagarika Dharmapala preached?

Literary life

Piyadasa Sirisena wrote his debut novel Vasanavantha Vivahaya Hewath Jayatissa Saha Roslin as an answer to the earlier novel Vasanavantha Pavula Saha Kalakanni Pavula (Lucky family and unlucky family) by Reverend Issac de Silva which promoted the Christian concept of family and Christian values. This novel was serialised in the journal ‘Ruwan Mal Dama’ in 1866.

Generally, a story is conceived in a writer’s imagination, and anybody who embarks on to write a novel as an answer to another novel naturally becomes unsuccessful. This was what happened to Piyadasa Sirisena’s first novel. According to Martin Wickramasinghe, if Sirisena had tried to inspire exclusively from folk poetry, folklore and Buddhist texts, he would have been the best folklorist and folk poet in the 20th century like Venerable Vetteve.

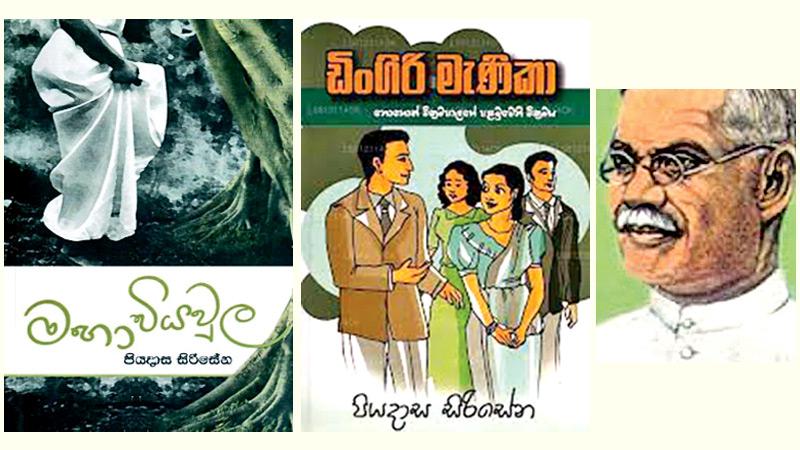

Piyadasa Sirisena was an enthusiastic writer. That’s why he wrote 19 novels and hundreds of poetry which indicates his genuine literary talent. Amongst his 19 novels, more prominent are; Apata Vechcha De (1909 – What happened to us),

Maha Viyavula (1909 - The great confusion), Tharuniyakage Premaya (1910 – The love of a young woman), Ashta Loka Dharma Chakraya (1916 – The wheel of eightfold universal laws), Adbhutha Aganthukaya (1928 – Weird stranger), Chintha Mankiya Rathnaya (1930 – The gem), Yantham Gelavuna (1931 – Barely survived) and series under the general title of Adventures of Kongoda Wickramapala.

Among these novels, Ashta Loka Dharma Chakraya (1916) was written during the 58 days of his imprisonment as a result of Sinhalese – Muslims riots in 1915. He was put behind bars for his fierce anti-colonial writings in the newspaper and the speeches he made at public gatherings. He was imprisoned along with other patriots such as F.R. and D.S. Senanayake, Walisinghe Harischandra, Henri Pedris and the rest, and Henri was later shot dead by British rulers’ orders for “arousing public sentiment”. In that sense, it was sheer luck that Piyadasa Sirisena was able to survive and write books.

Political commentator and detective

When considering Sirisena’s fiction, we can identify three kinds of novels. First are novels of socio – political theme, second are romantic novels and third are detective novels. But all these three kinds are characterised by full of nationalistic and anti-colonial thoughts.

The novels with socio – political themes include Apata Vechcha De (1909), Maha Viyavula (1909), Ashta Loka Dharma Chakraya (1916) and Sri Lanka Matha (1922), and needless to say they are highly consisted of nationalistic and patriotic thoughts.

How about his romantic novels? We all know the reason why he wrote his first novel, Jayatissa Saha Roslin. It was written as a rejoinder to the novel of Rev. Issac de Silva. So, it is not surprising that it includes elements of Sinhala Buddhists’ and nationalistic values - the book ends with Jayatissa, the protagonist, like the author, a persuasive public speaker arguing vehemently against Christianity, Western values, its ways of life and drinking, converting Roslin and her parents into Buddhism. His fourth novel Tharuniyakage Premaya (The love of a young woman) sounds a romantic love, but it is also embodied traditional cultural values and anti-colonial elements. In his Preface, he states that the novel was written with the aim of demonstrating the importance fostering morality and nationalism.

In his list of books, there consist six direct detective novels which are; Dingiri Menika Hevath Wickramapalage Palamuveni Vikramaya (1918), Vimalatissa Hamuduruwange Mudal Pettiy Hevath Wickramapalage Deveni Vikramaya (1919), Valavvaka Palahilavva Hevath Wickramapalage Tunveni Vikramaya (1921), Ishta Deviya Hevath Wickramapalage Hatharaveni Vikramaya (1925), Maheshvari Hevath Wickramapalage Pasveni Vikramaya (1937) and Debara Kella Hevath Wickramapalage Hayaveni Vikramaya (1944). But the typical feature of these books are while they present us detective narrative, they also bring forth a discussion of nationalism and moralism.

Piyadasa Sirisena never tried to conceal his aim of writing fiction which was didactic, to focus on what he perceived to be the moral decline visible in the country. But why was he so much obsessed by the socio-political theme? It is none other than he was grown up by traditional Sinhala – Buddhist cultural values, and on the other hand, he could see a severe moralisti decline in the contemporary society. So, he naturally sought to call attention to the imperative need for national cultural revival, in his preface to the novel Maha Viyavula, he makes the point that in writing his novels his intention is to promote nationalistic thought and patriotism.

Professor Wimal Dissanayake calls this attempt as cultural nationalism.

Cultural nationalism

Prof Dissanayake elaborates his concept – in fact, it’s a concept of sociologists – deeply in his book Sinhala Novel and the public sphere: “Piyadasa Sirisena can best be described as a novelist of advocacy; hence, his looming importance in the public sphere. His primary focus was on the promotion of cultural nationalism as a way of regaining self-esteem and re-possessing history. In order to achieve this goal, he dealt with a number of overlapping themes in his fiction. In the first novel that he published, Jayatissa Saha Roslin, the guiding theme is religion – the demonstration of the superiority of Buddhism over other religions. Apata Vechcha De constitutes a valorisation of indigenous cultural practices ranging from traditional customs, dress, indigenous forms of medicine, appropriateness of local garments.

In novels such as Tharuniyakage Premaya, Palamuveni Pasala Sirisena sought to explore the social role of women... His detective novel, Valavvaka Palahilavva, portrays the moral decadence of certain members of Kandyan nobility and in his novel, Vimalatissa Hamuduruwange Mudal Pettiya, the author has sought to pillory certain deficiencies discernible among Buddhist bhikkhus. Debara Kella directs the spotlight towards the perceived moral and spiritual decline among women. Adbhuta Aganthukaya has as its theme the harmfulness of liquor. What we see then, in Piyadasa Sirisena’s novels is a cluster of interesting themes that serve to underline his master theme of cultural nationalism.” (pp. 90 - 91)

In this way, Sirisena promoted cultural nationalism in order to regain the people’s self-esteem and re-possess the history which was vanished due to the advent of colonialists. Yet, Prof Dissanayake says the cultural nationalism has to be understood against the social consciousness in the country:

“His (Piyadasa Sirisena’s) espousal of cultural nationalism has to be understood against the increasing thickening of an urban consciousness in the country. This was particularly so in the Western and Southern provinces of Sri Lanka. The improvement in transport, railway lines and roads, connecting the capital and cities in the south, had the effect of bringing the villages into a complex network through which an urban consciousness circulated.

The establishment of English-language schools by missionaries, and English having been introduced to rural schools had the effect of opening doors for urban employment to village dwellers. The increase in the number of journals that were being published at the time, too, aided in this process of urbanisation of the consciousness. What is interesting to observe is that Piyadasa Sirisena was operating from within this changing social environment. He was working with and against the imperatives of the urbanisation of the consciousness of the people, and the rise of the national bourgeoisie, in order to achieve his declared aims in the public sphere.” (pp. 91)

What went wrong for Piyadasa Sirisena?

Was it correct that Sirisena made use of novel instead of newspaper to carry out his cultural discussion? Basically, novel is the medium for releasing one’s feelings or to express oneself, it is not a medium for releasing ideas. Yet, if the ideas come through a writer’s inner self – from his heart – he can disseminate his ideas through the novel without harming the artistic elements of it.

But with Piyadasa Sirisena, the ideas that he used in his novel, never came from his heart – they came through his mind – he saw things objectively. The result was that Sirisena’s fiction couldn’t touch the hearts of the reader. So, this is where he went wrong in the fiction.

The point that Sarachchandra pointed out in his critical analysis, Sinhalese Fiction, in 1943, with regard to Sirisena’s novels was also similar to this. He said that Sirisena has failed in his fiction as he tried to preach the reader rather than portray the things. Though some former members of Peradeni school including Wimal Dissanayake and Gunadasa Amarasekara, despised the efforts of Sarachchandra saying his criticism was wrong considering the time, the colonial period.

Sirisena was engaged in the fiction, he (Sarachchandra) was totally right, because he rightly focused on the text ignoring other things in the novel when criticising his books. However, we cannot neglect the talent and the novelistic elements in his fiction in the backdrop of colonialism.

And also, we never can bypass the discussion Sirisena put forward though he was unsuccessful in the media of novel.

Wickramasinghe’s thoughts on Sirisena

According to Martin Wickramasinghe, Piyadasa Sirisena is a humane, compassionate writer: “The responsibility of a compassionate writer is to fight for downtrodden people. Piyadasa Sirisena, in that sense, did his duty as a writer and a poet. A compassionate writer becomes a socialist because he relentlessly criticises the social oppressors which include Governors,

Officers and owners of massive wealth in defense of poor people. Sirisena hadn’t any knowledge about Socialism, but he was an innately socialist. Most of his novels reveal this fact.” (Ape Viyath Parapura haa Bhasha Samaja Parinamaya, pp. 22) Wickramasinghe further describes; “Piyadasa Sirisena unconditionally praised Sinhalese’ past – all the good things and bad things in the past. At the same time, despised all the things of foreigners. He did so not as a person with narrow vision, but as a person with patriotic feelings infuriated by seeing spiritual declining in the country resulted from the Western culture.” (pp. 22)

As mentioned earlier on, Sirisena would have been a best folk-narrator and folk poet if he ha tried to inspire from folk poetry, according to Wickramasinghe. He also speaks about the various elements in Sirisena’s novel: “Sirisena’s novels are filled with various items. There we can find novel, sermons, advices, insults, sarcasms, myths, poetry and folklore. Sirisena is a folk poet, basically. His great skills in folk poetry were mixed with some nonsense thoughts of learned people, both Sinhala and English. It was happened by associating uncultured Buddhists in the city and learning from them.

If Sirisena had tried to inspire exclusively from folk poetry, folklore and Buddhist texts, he would have been the best folk-narrator and folk poet in the 20th century like Venerable Vetteve in the past.” (Ape Viyath Parapura haa Bhasha Samaja Parinamaya, pp. 25 - 26)

Martin Wickramasinge does not comment on the novelist in Sirisena, instead admire the folk poet in him. Why, it was because he was unsuccessful as a novelist.

Legal text

Prof Wimal Dissanayake discusses about another aspect of Piyadasa Sirisena. He says his novel are constructed along the lines of a legal text. For instance, in his first novel, Jayatissa Saha Roslin, his ultimate objective is to convince the reading community through his narrative and argumentations the correctness and plausibility of his views and opinions.

“The author selects incidents, emphasises, episodes, presses into service rhetorical locutions deploys tropes, with the purpose of constructing a narrative of persuasion. We need to explore the concept of legal texts being narratives of persuasion against the background of mainstream thinking on law and literature. It is widely believed that law is objective, neutral, dispassionate, balanced and constitutes an impersonal way of arriving at the truth.

On the other hand, literature is subjective, partial and has a strong emotional content. It is contended that legal texts deal with determinate meanings and whereas literary texts are characterised by an indeterminacy of meaning. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that legal texts are no less subjective, partial, indeterminate than literary texts. Legal texts, whether these are narratives constructed by prosecutors or defense lawyers or the judge, are written in words. Hence, they are a form of writing, a textuality.” (Sinhala Novel and the Public Sphere, pp. 98)

Prof Wimal Dissanayake, here, tries to establish that Sirisena’s novels have a literary quality though there is a form of legal text in them. But this legal text element is a clear defect of his fiction. As stated above, it is a characteristic of Piyadasa Sirisena’s novel as we don’t see such defects in A. Simon de Silva’s fiction who wrote first Sinhala novel, Meena, in 1905.

Literary landmark

The novel of Piyadasa Sirisena is a landmark of the Sinhala novel more than a development of it.

He could develop the readership for Sinhala novel, albeit most of them were lay people.

However, he was a talented novelist. His talents are amply visible in the titles of his novels. For instance, the titles such as Adbhutha Aganthukaya (1928), Chintha Mankiya Rathnaya (1930), Pariwarthanaya (1934) and Adventures of Kongoda Wickramapala sound like nowadays’ titles of the novel and the young adult’s novel, while Apata Vechcha De (1909), Maha Viyavula (1909), Ashta Loka Dharma Chakraya (1916), Sri Lanka Matha (1922) and Yantham Gelavuna (1931) sound of a powerful political titles for nonfiction.

And there is another quality which we should admire in Piyadasa Sirisena. Speaking about his inspiration, he genuinely said that he was influenced by western novels to write his novels.

Though he was such an ardent admirer of old classical Sinhala texts, he admitted he started to write fiction by reading western fiction. Martin Wickramasinghe, on the other hand, said Sinhala fiction derived from Jataka stories and Sinhala folk-narratives.

Considering all this, Piyadasa Sirisena made a great landmark of Sinhala literature. Despite all the shortcomings, his novel is the base for Sinhala novel. Without him, Prof Sarachchandra also wouldn’t have embarked on to write his critical work, Sinhalese fiction, another benchmark of Sinhala literature. In a way, Sirisena was the one who merged the sophisticated reader with high taste and the general reader with low taste. Thus, he will continue to be an everlasting, most discussed and highly controversial writer in Sri Lanka like the heroes in his fiction until the Sinhala fiction is available for readers.