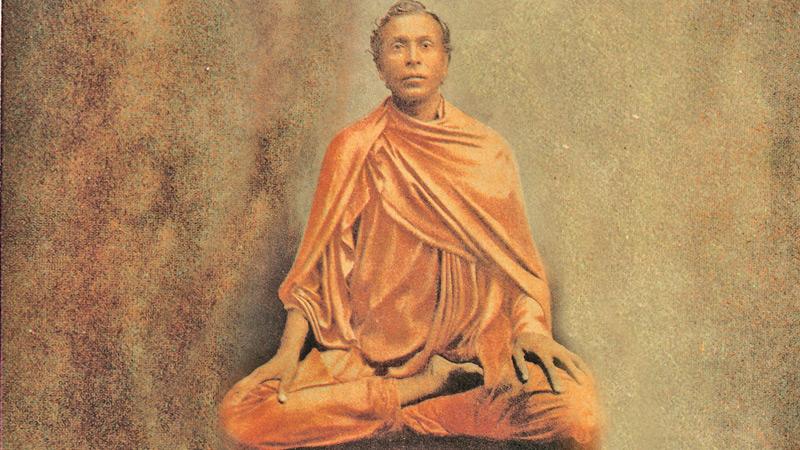

Anagarika Dharmapala’s 157th birth anniversary fell on September 17, 2021. Perhaps it is the right time to revisit his idea of the ‘united Buddhist world.’ The ‘united Buddhist world’ is a geographic and historically-linked spiritual, emotional and cultural landscape touched by Buddhism emerged in the late 19th century through the writings and work of the American Theosophist Henry Olcott, Indian thinker, Rahul Sankrityayan and Anagarika Dharmapala himself. I want to briefly look at how this was articulated in practice by Dharmapala.

What these 19th and 20th Century thinkers had in mind for Buddhism as a faith, as a cultural force and as an extended geophysical space far exceeded the limitations of localisations which had become inherent aspects of Buddhism in its historical evolution in terms of both cultural practices and its institutional locations in specific countries. Effectively, what they had in mind were ‘universalising’ features.

What these 19th and 20th Century thinkers had in mind for Buddhism as a faith, as a cultural force and as an extended geophysical space far exceeded the limitations of localisations which had become inherent aspects of Buddhism in its historical evolution in terms of both cultural practices and its institutional locations in specific countries. Effectively, what they had in mind were ‘universalising’ features.

Global religions, which spread across large areas of the world such as Islam, Christianity and Buddhism necessarily incorporates these universalising features. As I see it, ‘the united Buddhist world’ envisaged at this time was universal in its general embrace while equally as comfortable with the local. After all, Buddhism was a classic example of a universalising cultural force with very clear trends in localisation. However, seen from today, the 19th century idea of the ‘united Buddhist world’ is an unfinished history of what seems to be the initial imagination of a ‘Super State.’

Efforts to unite Asia

In certain ways, this specific spatio-spiritual imagination of ‘the united Buddhist world’ encompassed much of what we consider as South Asia today. It also spread as far as Japan and China in the east linking two kinds of broadly defined Buddhisms, known at the time as ‘northern’ Buddhism, centered in Japan and ‘southern’ Buddhism focused on Sri Lanka. It was only in 1907 that the reference to southern Buddhism acquired its new nomenclature as Theravada Buddhism by reworking an ancient term.

The issue is not that Buddhism, at the height of its power had not transgressed geographic borders from present day South Asia to places as far east as China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and so on, Afghanistan in the west and as far south as the Maldives. But by the 19th century and certainly by the time of the advent of colonialism in Asia, much of this power and influence was clearly lost.

So, by late 19th century, the notion of ‘the united Buddhist world’ was not a world as it once existed, but a world in contemporary times taking into account contemporary realities and needs but tracing the ancient terrain of Buddhism’s social and political influence as a reference to articulate its would-be contemporary borders.

Part of this reimagination depended on creating new networks and institutions. 19th and early 20th century cultural revival of Buddhism was at least partly influenced, supported and at times funded by colonial characters or benefactors in the West. For instance, most major South Asian or religious leaders of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who had created their own networks beyond South Asia, had such benefactors.

So, Anagaarika Dharmapala had Upasika Mary Foster Robinson as his main benefactor while Swami Vivekananda had American benefactors such as Henrietta Muller and Ole Bull. Sarath Amunugama notes in his book, ‘The Lion's Roar: Anagarika Dharmapala and the Making of Modern Buddhism’, the relationships these leaders had with their Western benefactors helped them find “a wider audience and saved them from the privations which were characteristic of earlier religious activists.”

With this kind of financial support, these leaders were able to “set up institutions and muster large groups of followers unlike their predecessors” writes Amunugama. Hon Dharmapala’s own diaries show very clearly how his ability to command American funding through his benefactors as well as his own considerable personal wealth ensured the institution-building enterprise of the wider Buddhist world that he imagined.

In certain ways, these institutions and practices in different locations in South and Southeast Asia as well as North America and Western Europe marked the cartography of the hoped-for ‘united Buddhist world.’ It is in this context that Hon Dahramapala set up the ‘Maha Bodhi Society of India’ in Bodh Gaya with its branches all over India and in other parts of the world. It was part of his spiritual world-building strategy. Affectively, Bodh Gaya was the veritable capital of this world. Hence, its political significance.

It is also as a part of this scheme that the group known as the Colombo Committee invented the Buddhist flag in 1885, which was soon afterwards modified to its present form by Henry Olcott to ensure that it was the same size and form like ‘national’ flags. In effect, the re-Buddhisised Bodh Gaya and the Buddhist flag came into being as corporeal political symbols of the ‘united Buddhist world’ Hon Dharmapala and other thinkers were attempting to formulate.

Spending his own wealth

My contention is that Dharmapala’s extensive international travels at the time projected the extent of ‘the united Buddhist world’ as he imagined as well as its extensions to the ‘West’, which he modeled on the Christian missionary expansion in the colonial world, which he constantly fought against in Sri Lanka.

Dharmapala spent most of his adult life away from Sri Lanka and much of this was spent in Calcutta and London. In 1889, 1896, 1902, 1913 and between 1925 and 1926 he travelled around the world looking for supporters and funds and establishing networks. He visited Japan four specific occasions and travelled to Akyab (1892), Shanghai (1894), Siam (1894), north India (1899 and 1923), London (1904), Hawaii (1913) and China, Korea and Boro Budhur (1913).

In 1925 and 1926, he toured Europe and the United States before he settled in London for a significant period of time in the context of which he established the first Buddhist temple in Europe. All this is well described in Stephen Kemper’s book, ‘Rescued from the Nation

Anagarika Dharmapala and the Buddhist World’. In addition to the stamina of the person, these travels also indicated the power of private capital in the religio-political enterprise he had embarked upon. His efforts were not funded by States or Governments, but by individuals including himself.

His institution-building activities were also geared towards the larger project of creating and popularising his idea of ‘the united Buddhist world.’ These activities come under two basic categories, which are intellectual as well as physical. That is, the building of intellectual infrastructure to promote his ideas by setting up journals, discussion forums etc. for the propagation of ideas on one hand, and the physical building of institutions on the other.

In the case of the former, the historical moment in which he operated played a crucial role. That is, the relatively easy availability of the printing press and the evolution of an international postal system allowed for his ideas to travel great distances in a relatively short period of time, just as much as the technological advances which allowed for the spread of train and steamship services also allowed for him to take the kind of relentless travel he undertook, in order to personally build his network.

In this scheme of things, he established and published weekly the Sinhala Bauddhaya in the Sinhala language for distribution in Sri Lanka. More importantly, he also published the ‘Journal of the Maha Bodhi Society and the United Buddhist World’, the English language newspaper, which he established in 1911 in Calcutta.

As Stephen Kemper notes, the title of his English language publication captures his hopes “for drawing Buddhists into a pan-Asian community linked to supporters in Europe and America.” Maha Bodhi Society of India itself, which he established in 1891 and survives up to now, was very much his society. He was “its only fulltime worker and the person who made ends meet” writes Kemper.

Dharmapala built Buddhist temples in his own lifetime in different places in India that were centrally implicated in the life of the Buddha as well as in the history of Buddhism, which included sites in Bodh Gaya, Kushinara, Saranath, Sancthci etc. He also established a major temple and the society’s head office in Calcutta, not because of that city’s association with the Buddha or Buddhist history, but due to its political importance in the empire given its status as the capital of British India until 1911.

Unfinished business for Buddhists

Despite his efforts, the project of ‘the united Buddhist world’ was never realised. It could not transcend many obstacles which were both political and personal. For one thing, local nationalisms in different places complicated Dharmapala’s universalising project. That is, prevailing strong local nationalisms from India to Japan and China simply did not allow for a serious discussion of ‘the united Buddhist world’, which would necessitate at least partial dismantling of some of these nationalist sentiments. This simply could not be overcome.

Beyond localised forms of nationalisms, he also had to face the challenges posed by other universalising projects, which ranged from British imperialism, Theosophy, Christianity and Western civilisation, all of which were countering his ideas of ‘the united Buddhist world.’ Besides, Hon Dharmapala’s relations with his adversaries and his supporters were often aggressive and confrontational, necessitated partly by the conditions of the times as well as his own personality. This also did not offer much hope for the kind of grand project he had in mind beyond a point.

Finally, the idea of ‘the united Buddhist World’ could not be achieved as it was greater than himself and its political and cultural implications were ahead of its time. In this sense, that failure is not too dissimilar to our collective inability to achieve South Asia itself as a collective and cooperative social and cultural space despite the rhetoric of SAARC.

In his time as well as today, the ideals of the nation and the power of local identities are far too strong to construct anything grander, which needs to self-consciously move away from some aspects of localisations and nationalisms and moved towards universalism.