The prize of prizes, the Nobel Prize for literature 2021 was awarded to Abdulrazak Gurnah, a Tanzanian-born novelist and academic, based in the United Kingdom. As always, the winner was not among the immediate favourites for the honour this year though he deserved it according to critics.

British bookmakers calculated five authors favoured for this year’s Prize: Kenya’s Ngugi wa Thiong’o, French writer Annie Ernaux, Japanese author Haruki Murakami, Canada’s Margaret Atwood and Antiguan-American writer Jamaica Kincaid. But eventually, it went to someone whom nobody guessed.

Behind the scene

Abdulrazak Gurnah |

Abdulrazak Gurnah was born on December 20, 1948 in Sultanate of Zanzibar, an Indian Ocean archipelago, which would unite with the mainland territory Tanganyika to form Tanzania. In 1963, Zanzibar became independent, and its ruler, Sultan Jamshid, was overthrown the following year by a revolution which started to end the political dominance of the minority Arab population over the African majority.

The next months and years were dominated by deep division, tensions and vengeance. Gurnah wrote in 2001, owing to the revolution, “thousands were slaughtered, whole communities were expelled and many hundreds imprisoned. In the shambles and persecutions that followed, a vindictive terror ruled our lives.”

In the midst of this turmoil, he and his brother escaped to Britain as refugees. It was in 1967, and at the time, he was 18 years old. But before this, he took a one-month tourist visa that allowed him to travel to Britain where he enrolled for A-level studies at a technical college named Christ Church College in Canterbury, southeast England whose degrees were at the time awarded by the University of London.

Gurnah’s first language is Swahili, but at the college he studied in English. As a refugee himself, he saw the tragic plight of his fellow refugees, and couldn’t come back his own country to see his parents as well. This created homesickness and loneliness which affected him very much. In the end, when he was 21, he automatically started to writing down thoughts in his diary – it is in English as he was used to it. This initial scribbling gradually turned into longer reflections about home; and eventually grew into writing fictional stories about other people.

The writing, then, became his habit. Gurnah used it as a tool to understand and record his experience of being a refugee, living in another land, and the feeling of being displaced. These first stories also became Gurnah’s first novel, ‘Memory of Departure’ published in 1987. This debut book set the stage for his ongoing exploration of the themes of “the lingering trauma of colonialism, war and displacement” throughout his subsequent novels, short stories and critical essays.

But how did he become a writer suddenly? Was it his childhood dream? Following is how he answered that question:

“It (idea of becoming a writer) never occurred to me. It wasn’t something you could say as you were growing up, ‘I want to be a writer.’”

He assumed he would become “something useful, like an engineer.” But later Gurnah attributed whole thing to his displacement in a foreign country:

“The thing that motivated the whole experience of writing for me was this idea of losing your place in the world,” he said in an interview.

After the general degree from the Christ Church College, Canterbury, Gurnah moved to the University of Kent, where he earned his PhD, with a thesis titled ‘Criteria in the Criticism of West African Fiction’ in 1982. At the time he was working on his debut novel as well.

From 1980 to 1983, Gurnah had a chance to become a visiting lecturer at Bayero University Kano in Nigeria. He went on to become a professor of English and postcolonial literature at the University of Kent, where he taught until his retirement in 2019. Anyway, because of his success in university education he was able to return to his motherland in 1984 and also seeing his father shortly before his death.

Literary canon

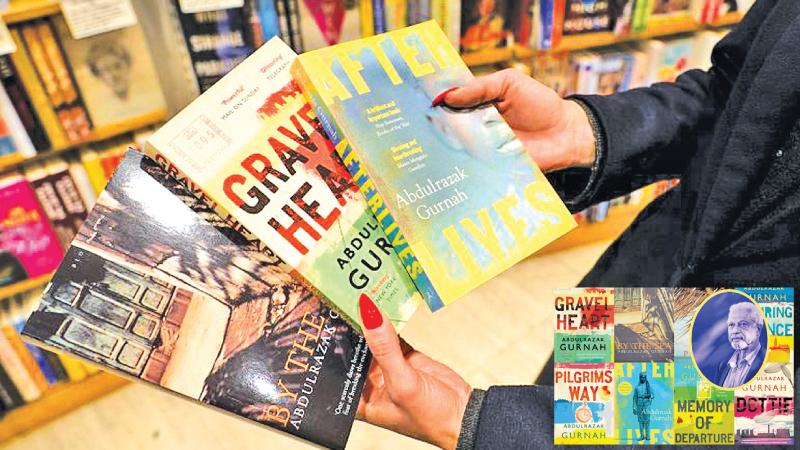

Gurnah’s body of work includes 10 novels which are ‘Memory of Departure’ (1987), ‘Pilgrims Way’ (1988), ‘Dottie’ (1990), ‘Paradise’ (1984), ‘Admiring Silence’ (1996), ‘By the Sea’ (2001), ‘Desertion’ (2005), ‘The Last Gift’ (2011), ‘Gravel Heart’ (2017), and ‘Afterlives’ (2020). Among them, ‘Paradise’ was shortlisted for the Booker, the Whitbread and the Writers’ Guild Prizes while ‘By the Sea’ was longlisted for the Booker and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. The novel ‘Desertion’ was shortlisted for the 2006 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize while ‘Afterlives’ was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Fiction 2021 and longlisted for the Walter Scott Prize.

Gurnah is an author of a few short stories as well. They are ‘Cages’ (1984), in ‘African Short Stories’, ‘Bossy’ (1994) in ‘African Rhapsody: Short Stories of the Contemporary African Experience’, ‘Escort’ (1996) in ‘Wasafiri’, ‘The Photograph of the Prince’ (2012) in ‘Road Stories: New Writing Inspired by Exhibition Road’, ‘My Mother Lived on a Farm in Africa’ (2006) in ‘NW 14: The Anthology of New Writing’, ‘The Arriver’s Tale’ in ‘Refugee Tales’ (2016), ‘The Stateless Person’s Tale’ in ‘Refugee Tales III’ (2019).

He also produced a few nonfiction works.

Because of all these literary endeavours, in 2006, Gurnah was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and in 2007 won the RFI Témoin du Monde (“Witness of the world”) award in France for the novel ‘By the Sea’.

A Tanzanian writer?

Many Tanzanians acknowledge recognition of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s work among the handful of African novelists to have won the prestigious prize, but others question whether Tanzanians can truly claim the England-based writer as their own. Most of his books haven’t been published in Tanzania, and his works never have become text books in the schools in Zanzibar.

Gurnah is not a household name in Tanzania. Gurnah’s award, back home, sparked long and passionate online discussions about belonging and identity, invoking – rather unexpectedly – politically charged debates about the union between Zanzibar and the mainland, “whose relationship has not always been rosy,” according to critics – “Even though Zanzibar is semi-autonomous, with its President and Parliament, there continues to be aspirations for more independence from the Union Government,” social media recorded.

However, the Presidents of Tanzania and semi-autonomous Zanzibar hailed Gurnah’s achievement:

“The prize is an honour to you, our Tanzanian nation and Africa in general,” Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan tweeted. For his part, Zanzibar leader Hussein Ali Mwinyi said, “We fondly recognise your writings that are centred on discourses related to colonialism. Such landmarks bring honour not only to us, but to all humankind.”

Though some Zanzibar people do not accept Gurnah as their own, Gurnah himself stressed his close ties to Tanzania in an interview with AFP news agency:

“Yes, my family is still alive, my family still lives there. I go there when I can. I’m still connected there. I am from there. In my mind I live there.”

He told a news agency, “Such a complete surprise that I really had to wait until I heard it announced before I could believe it,” he tweeted, dedicating the prize to his native people: “I dedicate this Nobel Prize to Africa and Africans and to all my readers. Thanks!”

Inspiration

In terms of inspiration, Gurnah draws on the imagery and stories from the Quran, as well as from Arabic and Persian poetry, particularly ‘The Arabian Nights’. The country he grew up (Zanzibar) also inspires Gurnah throughout his literary life. Though, he hasn’t lived in Tanzania since he was a teenager, it continues to inspire him. He said that his homeland always asserts himself in his imagination, even when he deliberately tries to set his stories elsewhere. “You don’t have to be there to write about a place,” he said. “It’s all in the fibre of everything you are.”

Slow writer

Abdulrazark Gurnah himself is not seeking readers. He only focuses on his work, not the readers. He has never been vigilant on the sales of his books. He never hastens to publish books in a quick time. He takes time to write. According to Alexandra Pringle, his editor-in-chief of Bloomsbury Publishing for 20 years and now Executive Publisher, “The five novels I’ve published came in five-year gaps: ‘Desertion’, ‘The Last Gift’, ‘Gravel Heart’ and, last year, ‘Afterlives’.” (The Hindu, October 16, 2021)

Gurnah, like so many other authors who choose to write in English despite it’s not being their first language, has thought deeply about questions of tradition, influence, and canon. He is a culture-conscious writer which is a basic necessity for a writer.

Price of the prize

Abdulrazark Gurnah is 73 years old. For the prize, he will be awarded a gold medal along with 10 million Swedish kronor ($1.14 million). The money comes from a bequest left by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1895. Gurnah said on the prize money: “It’s just great – it’s just a big prize, and such a huge list of wonderful writers - I am still taking it in.”

Gurnah is the first black African author to have won the award since Wole Soyinka in 1986. He is the fourth black person to win the prize in its 120-year history – other three are Wole Soyinka, a Nigerian writer (1986), Derek Alton Walcott, a Saint Lucian poet and playwright (1992), Toni Morrison, a Black American writer (1993). Based in Britain and writing in English, Gurnah, joins Soyinka as the only two non-white writers from sub-Saharan Africa to win the world’s most prestigious literary award.

Since 1986, it has been won by Egypt’s Naguib Mahfouz and three white African writers - South Africans Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee, and Doris Lessing, who was raised in British-ruled Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. Out of 117 times of awardees, only 16 women have won the prize.

Refugee crisis and colonialism

Gurnah, a refugee-turned writer came from a colonised country. With this prize, he hopes that issues such as the refugee crisis and colonialism, which he has experienced, will be “discussed” profoundly.

“These are things that are with us every day. People are dying, people are being hurt around the world - we must deal with these issues in the most kind way,” he said. He added, “I came to England when these words, such as asylum-seeker, were not quite the same - more people are struggling and running from terror states.

“The world is much more violent than it was in the 1960s, so there is now greater pressure on the countries that are safe, they inevitably draw more people.”

When considering all these facts, the selection of Abdulrazak Gurnah for the Nobel literary Prize 2021 is reasonable, because it, not only opens a window to a new literary pathway, but also direct us to see a nowadays’ profound humanitarian crisis resulting from a tug of war between world leaders.