We live in an age where technology devices are used for day-to-day life. Can you imagine spending a day without mingling with electrical and electronic equipment? We’re betting that the majority of your responses would be NO. Advancement of technologies gives to provide a great deal of convenience to human life, equally we do love to have it.

Each year, the use of electrical and electronic equipment increases by around 2.5 million metric tons (Mt). Simultaneously, the prevalence of obsolete, malfunctioning or irreparable electronic equipment grows daily. Such electronic devices that can no longer be used for their intended purpose are termed e-waste. E-waste is one of the most paramount and pressing issues of our time, however, it is frequently overlooked.

In 2019, the globe generated 53.6 Mt of e-waste, an average of 7.3 kg per capita. Asia becomes the top by producing 24.9 Mt of e-waste, followed by the Americas (13.1 Mt), Europe (12 Mt), Africa (2.9 Mt), and Oceania (0.7 Mt). Since 2014, worldwide e-waste generation has increased by 9.2 Mt, with a forecast increase to 74.7 Mt by 2030. Today, it has become the world’s fastest-growing waste stream, rising at nearly three times the rate of other municipal solid waste streams.

Accounting for those factors, United Nations has stated that e-waste will be the next Tsunami for many countries. Recycling is the best solution to address the issue because the valuable materials are reused to make new equipment and minimise environmental contamination.

However, such practices are not at a satisfactory level where the most of generated e-waste in the world are not directed to proper recycling. According to the latest findings of the Global E-waste Statistics Partnership-2021, just 9.3 Mt of e-waste is adequately recycled in 2019, and the fate of the remaining 44.3 Mt is uncertain.

e-waste scenario

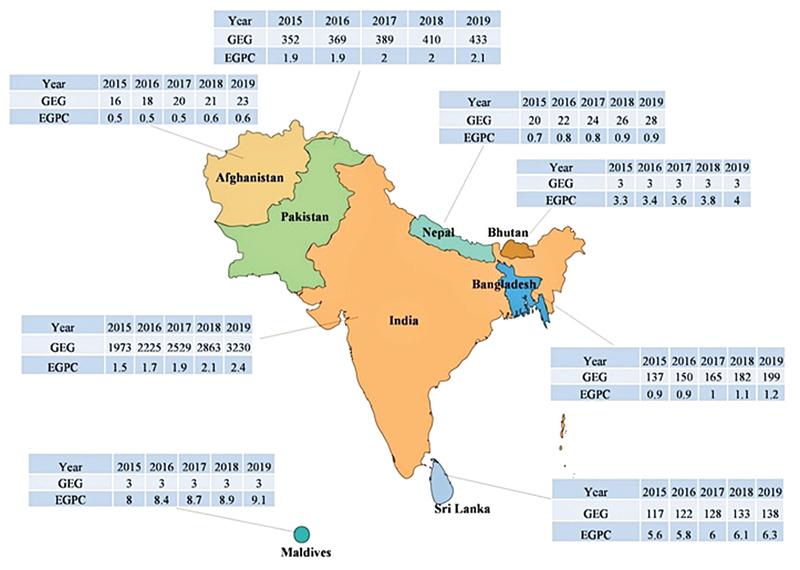

To be precise, the Global E-waste Statistics Partnership-2021 estimates that 4,057-kilotons (kt) of e-waste were produced by South-Asia in 2019. About one percent increase in e-waste has been observed in recent years. The trend is projected to continue in the coming years too.

India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are the top three nations in South Asia that produced 3230 kt, 433 kt and 199 kt of e-waste in 2019. However, these figures appear to be underestimated, and real values could be far higher. Figure 1 depicts the amount of e-waste generated in the recent past in South Asia.

The e-waste scenario in Sri Lanka is also getting worse by producing more waste each year and generating 138 kt of e-waste in 2019, also holds the fourth place in South Asia. This value could be doubled in the next ten years, if no adequate measurements are taken. CFL bulbs, mobile phones, television sets, batteries, computers and toners are by far the major contributors to the amount of e-waste in Sri Lanka.

The short lifespan of those electronic products is the main contributor to the growing e-waste crisis. In contrast, comparatively, air-conditioners, freezers, refrigerators and electrical cook-stoves like products have a greater life span and to become e-waste takes generally over ten years. Some electrical and electronic equipment and their expected average lifespan indicate in table 1.

How we aim to repair the broken electrical and electronic equipment is another consideration. Unlike earlier, today most electrical and electronic equipment cannot be used for long and are more prone to get damaged or malfunction. Therefore, it helps to slow down the rate of e-waste generation by repairing and reusing the products. Nonetheless, rather than repairing, the majority of people in developed countries try to buy a new one. The next concern is whether or not all of the broken electrical and electronic equipment can be repaired.

In Sri Lanka, we’ve recognised that on average, around 5-15 percent of items sent to repair shops are returned without being repaired. This occurs owing to the irreparable nature and the high price to repair. LED TVs are becoming increasingly popular around the world, including in Sri Lanka, and if broken (common panel issues), they are costly to fix. As a result, consumers eventually make the choice to get a new, up-to-date television set. It is obvious that the continuous expansion of high-tech electrical and electronic equipment has led to an exponential increase in the volume of e-waste.

Catastrophic nature

Most electrical and electronic equipment contain toxic compounds. Once considered e-waste, it contains over a thousand different compounds and is extremely complex in nature. Some substances emitted by e-waste are said as non-hazardous, while many others are considered hazardous. Those hazardous substances include heavy metals such as; antimony, arsenic, bismuth, cadmium, cobalt, copper, indium, iron, lead, lithium, mercury, molybdenum, nickel, and palladium, silver, tin, titanium and vanadium, also many more organic chemicals.

Informal handling and management practices facilitate bringing those embedded toxic compounds to the surface, posing risks to humans and the environment. Once E-waste is dumped in a landfill, trace elements can break down, leach into the deeper soil and contaminate the groundwater. The groundwater could be the source many of freshwater resources. This poisonous water consumed by humans or animals leads to many diseases. Also, the plants/crops can take up this water. Consumption of such crops also creates similar threats. Labourers who are working in informal e-waste recycling warehouses are prone to significant risks due to direct contamination. In Bangladesh, over 50,000 children are involved with informal e-waste collecting and recycling practices.

Over 15 percent of child workers die each year as a result of unsafe working environments. Over 83 percent are exposed to harmful elements, becoming sick and suffering from a long-term illness. As reported in India, similarly, many workers are showing prolonged allergies and dermatitides such as rashes or itching, headache, burning of eyes, breathing difficulties and neurological symptoms such as hand-and-feet numbness.

Refrigerators like some temperature exchange equipment release greenhouse gases, which contribute to global warming. Some 98 Mt of CO2-equivalents were emitted into the atmosphere as a result of improperly managed discarded refrigerators and air conditioners, accounting for about 0.3 percent of global energy-related emissions in 2019.

E-waste handling and management

Consumer behaviour and collecting mechanisms for generated e-waste are important considerations in its effective management. In light of the problems associated with e-waste, in the recent past, several programs have been made independently by the Local Government and the private sector. Local Government bodies have launched a program to collect e-waste, mainly from households. Several private sector institutions organised an e-waste collection week to collect domestic waste. There are only 13 e-waste collectors (and exporters) in the island and formal waste collection seems to be limited.

On the other hand, many collections are restricted to the Western province, particularly to Colombo, while it is also limited to collecting certain types of e-waste. It mostly excludes the collection of CFL and fluorescent bulbs, due to the handling difficulties (hazardous due to the presence of heavy metals such as mercury). No formal recycling facilities are available in Sri Lanka. Nowadays, the trend is to use LED lamps, which is a good movement, however, short lived low-quality bulbs are getting abandoned. In future, this could be the top-ranked e-waste production in Sri Lanka.

Tourist hotels, large companies, factories and governmental departments typically channel their e-waste to formal collectors. Storing e-waste is a common ill-practice in Sri Lankan households as well as burying, burning and throwing into the open areas. People also dispose of e-waste to local government municipal collators, sometimes mixing it with other solid waste. The main reason for disposing of e-waste in an unfavourable manner is a lack of knowledge where the majority of the people treats e-waste as common solid waste. The lack of effective household collection mechanisms exacerbated the problem.

Rather than the business promotion, the buy-back offer given by the electronic showrooms is also a kind of e-waste collecting process, which ultimately leads to formal collectors and recyclers. The most informal collection was recorded in the island by involvement with plastic and metal collectors. They may value the e-waste for plastic and the metals and buy at the doorsteps. As informal collectors understood that electronic repair shops also produced a considerable amount of e-waste, so they purchase it for a good deal from them. The gathered waste by the plastic and metal collectors is handed over to the localised collecting shops, then could be directed to Colombo for informal processing.

The country’s formally collected e-waste is either adequately recycled or exported. As a good business, also as no facilities in Sri Lanka to recycle, some of the selected e-wastes such as printed circuits, laptop batteries (Telecommunication battery scrap) are exported to Japan, Korea and Europe. This has led to generating foreign exchange to the country.

Legal regime of e-waste

The responsibility for the management of e-waste is assigned to the Central Environmental Authority (CEA). As a part of the National Environmental Act, in 2008, Hazardous Waste (Scheduled Waste) Management Rules were promulgated. Accordingly, every e-waste generator, collector, storer, transporter, recover, recycler and disposer must get a licence from the CEA.

The CEA is responsible for granting approval to export e-waste in line with appropriate norms. The Department of Import and Export Control is in charge of regulating the import of electronic equipment and mobile phones. The Sri Lanka Standards Institution determines the standards applicable in the import and manufacture of electronic and electrical equipment in Sri Lanka and investigates whether such products comply with appropriate standards.

The Telecommunications Regulatory Commission of Sri Lanka contributes to the importation of mobile phones by allowing the importation of phones that meet the commission’s requirements, also co-ordinates in the handover of the used communication equipment, to the formal collectors. Although e-waste rules exist, proper e-waste management remains debatable in the island. Therefore, the country needs to take steps to offset the negative effects of e-waste, as well as reduce waste generation.

Mandatory actions

Sri Lanka needs to bring in legal provisions to solve this mounting issue. Filling the gaps of policies is mandatory. Hazardous Waste Management Rules (2008) didn’t include the condition that the manufacturer or the agents should carry out the disposal. Imposing stringent rules is a more forceful but difficult strategy to reduce awful handling. Therefore, much attention should be paid by bridging the other lapses.

Another concern that needs to be addressed is the lack of adequate formal e-waste collection. Formal collectors reach to collect the waste from many commercial and governmental institutions, though fail to collect waste from households and localised electronic repair centres. It is also needed to lift the formal sector to promote and increase recycling facilities and to establish island-wide e-waste bins at common places to facilitate the public to dispose of their waste.

An important way to control the generation of e-waste is to strengthen the barrier of importation of low quality electrical and electronic equipment and provide a mandatory considerable warranty period for each of this equipment in the local market. People should be educated at the grassroots level on the hazards of e-waste.

(The writers are lecturers of Eastern University of Sri Lanka.)