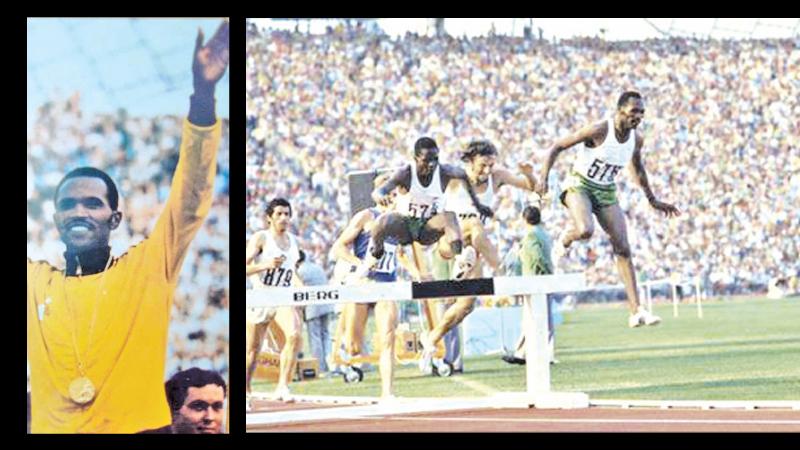

One of Kenya’s greatest Olympic athletes, Kipchoge Keino, universally known as ‘Kip’, is one of the world’s most admired sporting heroes. He was one of the early role models who inspired the great Kenyan tradition of distance running.

His courage and determination in winning a gold and silver medal in the Mexico City 1968 Summer Olympic Games, despite suffering from a gallbladder infection, endeared him to sports lovers around the world. That drive and single-minded determination to succeed against the odds has today made him one of the great benefactors to underprivileged children in Kenya.

In 2000, he became an honorary member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). In 2012, he was one of 24 athletes inducted as inaugural members of the IAAF Hall of Fame.He was the President of the Kenyan Olympic Committee until 2017. Kip is best known for his training at 1800m above sea level, which helped to introduce high-altitude training as a technique to improve running time at any altitude.

Birth and Early Career

Kip Keino byname of Hezekiah Kipchoge Keino was born on January 17, 1940 in Kipsamo in the Nandi Hills in the Western Kenya. In his local language, the name ‘Kipchoge’ means ‘born near the grain storage shed’. Keino’s father, a long-distance runner, encouraged his son in the sport.

When he was still very young, both his parents died and so he was brought up by his aunt.A member of the Nandi tribe, after finishing school, he joined the Kenya Police worked as a physical training instructor before becoming an athlete. Prior to that, he played rugby.

Like many children in rural Kenya, when he started primary school he had to run to get there. ‘I ran in my bare feet four miles to school in the morning,’ he once said. ‘Then I ran home for lunch, again for afternoon school and back at the end of the day. I did this every day until I left school.’

When he wasn’t running to school and back, Keino was often sent out to herd the family’s goats, which could involve trotting around after them for hours at a time. All of this physical activity, done in bare feet and at high altitude, laid the foundations for a career as a distance runner.

But in the early 1960s, athletics was still purely an amateur sport, so getting started for a poor Kenyan boy was challenging. Kip began his international career in 1962 when he set a Kenyan record in the Mile.

His first international exposure was when he made the Kenyan team for the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia, where he came 11th in the Three Miles. At the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, he represented Kenya in their first games as an independent nation, finishing fifth in the 5000m.

In both 1964 and 1965, at the first and second African Games, he was champion at 1500m and 5000m. At the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Kingston, Jamaica, he won gold medals in both the Mile and Three Miles.In the Edinburgh 1970 edition of the Commonwealth Games, Keino won the 1500m and was third in the 5000m.

On August 27, 1965, Keino lowered the 3000m world record clocking 7:39.6 in his first attempt at the distance. Later in that year, he broke the 5000m world record with a time of 13:24.2.

Mexico City 1968 Olympics

At the Mexico City 1968 Olympics, Keino suffered from severe abdominal pains. Yet, he competed in six distance races in eight days.

In his first final, the 10,000m, Kip had been leading, when with a few laps to go, he felt a tremendous pain in his side and collapsed on the infield. When the stretcher-bearers came to get him, he jumped back up and finished the race, but he was disqualified for leaving the track. His compatriot Naftali Temuwon Kenya’s first-ever Olympic gold medal.

Four days later, Keino was back on the track in the 5000m final and, despite a recurrence of his abdominal pain, he managed to stay the course and earn a silver, trailing Mohamed Gammoudi of Tunisia by barely a metre, with Temu running strongly again to claim the bronze.

Three days later, on the morning of the 1500m final, for which he had also qualified, Keino was still suffering stomach pains. He was visited in bed by a doctor, who told him he had a serious problem with his gall bladder and strongly advised him not to run. Keino recalls telling the doctor, “I’m running the 1500m. It’s a very short event, so let me run.”

Keino was told to stay in bed and to sleep, but when the doctor left, he got dressed and went to catch a bus to the stadium. However, on the way there, the bus got stuck in traffic. “I realized I was late,” says Keino. “So, I jumped out of the bus and I ran all the way, something like two kilometres, to the stadium.”

Keino was told to stay in bed and to sleep, but when the doctor left, he got dressed and went to catch a bus to the stadium. However, on the way there, the bus got stuck in traffic. “I realized I was late,” says Keino. “So, I jumped out of the bus and I ran all the way, something like two kilometres, to the stadium.”

When he got inside the stadium, they were just calling the runners for the 1500m final. Despite his pain, Keino, with help from teammate Ben Jipcho, set a furious pace over the length of the race, negating Ryun’s powerful finishing kick.

Wary of the impact of the high altitude of Mexico City, where the heart and lungs have to work harder to deliver oxygen, Ryun calculated that a time of 3:39 should be enough to claim gold – well outside his own world record of 3:33. So when Ben Jipcho set off from the gun at a ferocious pace, Ryun let him go.

There’s little doubt that the altitude in Mexico played a part in Keino’s success in 1968. With most of Kenya’s athletes coming from the high-altitude Rift Valley region, they were already adapted to the conditions in a way the Americans and Europeans weren’t.

With two laps to go, Keino hit the front and pushed on, reaching the 800m mark in 1:55, making Coleman splutter into his microphone that the pace was ‘near suicidal’. Ryun, meanwhile, was sticking to his plan and sitting back off the leading group in about eighth place.

Everyone waited for Keino to wilt in the blazing afternoon sun, but his pace remained relentless, and by the time he got to the final 200m, he was still well clear. He romped home in a new Olympic record of 3:34.91, claiming 1500m gold by almost three seconds in what is still the biggest winning margin in the event’s history and the record stood till 1984.

In Mexico City Olympics, the Kenyan athletes won eight medals, including three golds, but none had more impact on the sport than the 1500m final.

Derek Thompson, who was then a 10-year African American living in the projects in Harlem, New York, recalls watching the race on a black and white television with a fuzzy reception, “You have to remember this was 1968, the civil rights movement was happening in America. It was incredible to see Kip Keino winning.”

“Kip had no formalized training, no sophisticated coaching. He just grew up running to school and back, while Ryun was the darling of the US team – he wasn’t supposed to get beaten by some guy from a village in Africa.”Thompson would take the memory of that day into adulthood and would eventually meet the man who inspired him so much.

Lasting Legacy

It may not have been the only or even the first Kenyan victory. Moorcroft remembers watching the race in awe as a 15-year. “Other African athletes won medals at that Olympics, but there was just something special about Kip, the way he controlled the race, that was so impressive. There was something wonderfully spontaneous about the way he ran. He didn’t have sophisticated training like Ryun, but he was smart. He out-thought Ryun. And he did it with a smile on his face.”

For Derek Thompson, it was Keino’s reaction to winning that impressed him as much as anything. “I remember how gracious he was in victory,” he says. “After he won, he went over and hugged Ryun. I was so inspired. Here was someone who looked like me, running distance races and winning.”

So inspired was Thompson, in fact, that he went on to become track coach for the Ivy League Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and years later he took his family on a trip to Kenya in search of his hero. He ended up in Kip’s sports shop in Eldoret. “When he met me, he didn’t know me, but he was so gracious, and he invited me and my family to stay with him.”

By then, Keino was long retired from running, and had set up a school, a training camp for upcoming athletes and an orphanage – all of which he still runs today. “What he was doing with the orphanage really resonated with my wife,” says Thompson. “We have to start a foundation,” she said. So, we started the “Kip Keino Foundation.”

“Kip’s philosophy of caring about people, and the young, in particular, inspired me, and one of my major goals in life has become to help young people in any way that I can,” says Thompson, who still dedicates much of his time to projects in Kenya.

But Keino’s biggest legacy was inspiring and instilling belief in a generation of runners closer to home. If you spend time in Kenya today and ask the runners who most inspired them to take up the sport, you will still hear the name ‘Kip Keino’ repeated again and again. “Kip Keino is the father of Kenyan running,” they will tell you.

“Kip Keino leaves behind not only a legacy in Kenyan running, but in Africa and the world of sports,” says the Irish Patrician Brother Colm O’Connell, one of the most successful coaches in Kenya’s history, who has been living and coaching in Iten, in the Rift Valley, since 1976. “He put down a marker in middle distance running, an area which may have been considered the prerogative of the western world at the time. He played a massive role in putting the newly established independent nation of Kenya on the map.”

“It was the start of the African dominance,” says Moorcroft. “Sure, the altitude helped, but it was waiting to happen. Kip is the daddy of the African revolution.” After Keino, things changed quickly. At the Munich 1972 Olympic Games, Kenyans won a further six medals, with Keino back again to cement his status as a legend by winning a silver in the 1500m and an unexpected gold in the 3000m steeplechase, an event he had barely ever run before.

At the Munich 1972, Keino entered the steeplechase even though he had very little experience as the 5000m final in the Summer Olympic program clashed with his main event, the 1500m. Still, he was able to out-kick teammate Ben Jipcho and secure the gold medal. Six days after this victory, he added a silver in the 1500m.

Personal Best Achievements

800m - 1:46.41 (Munich 1972);

1500m - 3:34.91 (Mexico City 1968); Mile - 3:53.1 (Kisumu 1967);

3000m - 7:39.6 (Helsingborg 1965); 5000m - 13:24.2 (Auckland 1965); 10,000m - 28:06.4 (Leningrad 1968); 3000m Steeplechase - 8:23.64 (Munich 1972).

Retirement and Services to Humanity

He retired from athletics in 1973, a Kenyan hero, but there was much still to come from this remarkable man. He and his wife Phyllis purchased a farm in Eldoret, which they converted into an orphanage, the Kip Keino Children’s Home. “We started with two children, then it went to six, then ten. Now it’s up to 90. We give them shelter and love. Many of these children who lived with us as orphans have gone to university, some are doctors, and when you see them with their own families living well in society, I feel very happy,” he says.

The Keino family realized a lifelong dream by establishing the Kip Keino Primary School in 1999, and the Kip Keino Secondary School in 2009, funded by various donations. Almost 300 children age 6 to 13 attend the school. In 2001, he won the Laureus Sport for Good Award for his charitable work and was elected to the Laureus World Sports Academy.

The Keino family realized a lifelong dream by establishing the Kip Keino Primary School in 1999, and the Kip Keino Secondary School in 2009, funded by various donations. Almost 300 children age 6 to 13 attend the school. In 2001, he won the Laureus Sport for Good Award for his charitable work and was elected to the Laureus World Sports Academy.

With his wife, Phyllis Keino, he has dedicated significant efforts to humanitarian work in Eldoret, Kenya. Their son Martin was a two-time NCAA champion and highly successful pace-setter.

Kip Keino is on the cover of the October 1968 issue of Track and Field News, the first issue following the Olympics. He also shared the cover of the September 1969 issue with Naftali Bon.

For his work with orphans, he shared Sports Illustrated magazine’s “Sportsmen and Sportswomen of the Year” award in 1987 with seven others, characterized as “Athletes Who Care.” In 1996, Kipchoge Keino Stadium in Eldoret was named after him.

In 2007, he was made an honorary Doctor of Law by the University of Bristol. Earlier, Egerton University in Nakuru had awarded him an honorary degree.

Later Keino served as President of the National Olympic Committee of Kenya.In July 2012, he received further recognition from the City of Bristol after the Kenyan Olympic Committee, under his presidency, made Bristol the training base for its athletes in preparation for the London 2012 Olympics.

The Bristol City Council awarded him freedom of the city, making him the first to receive this honour from Bristol since Sir Winston Churchill.

On August 5, 2016, at the Olympic opening ceremony in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Keino was awarded the first Olympic Laurel, for outstanding service to the Olympic movement. On May 14, 2021, Jovian asteroid 39285 Kipkeino, discovered by astronomers at Spacewatch in 1997, was named in his honor.

The sports shop he owns is located on a bustling street in central Eldoret, high up in Kenya’s Rift Valley region. It’s a simple shop, with trophies on a shelf on the back wall and one large cabinet that doubles up as the shop counter. Inside the cabinet, folded in piles, are non-branded school rugby tops and athletics vests.

Kip Keino talks so softly it’s hard to hear him over the noise of the street outside. But he smiles as he recounts the story behind one of the greatest moments in athletics history. “I was in serious pain,” he says. That’s why “I collapsed in the 10,000m at the Olympic stadium in the Mexico City in 1968.”

His tremendous success on the track and his commitment to the welfare of Kenya made him one of the nation’s most-beloved heroes.

(The author is the winner of Presidential Awards for Sports and recipient of multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. He can be reached at [email protected])