On August 29, 1943, the 43 Group was formed in Lionel Wendt’s house at Guildford Crescent, Cinnamon Gardens. There are conflicting accounts of who took part in the first meeting and who did not.

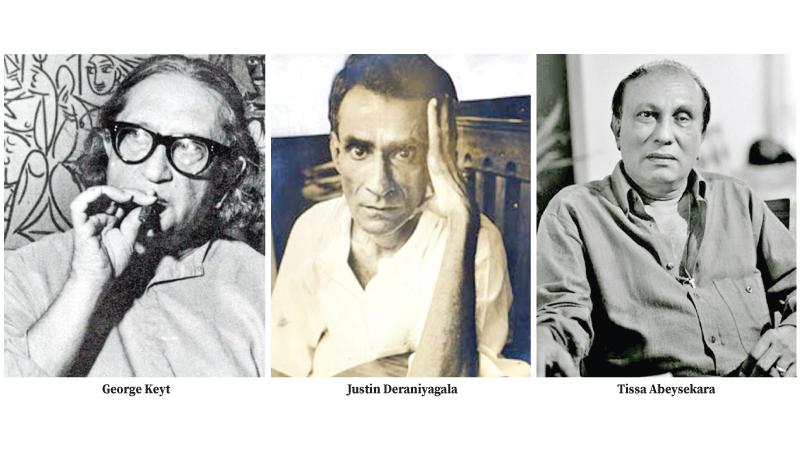

Lester James Peries remembered seeing George Keyt, Justin Deraniyagala, Geoffrey Beling, and Manjusri, while Richard Gabriel remembered coming across Deraniyagala, Beling, Lester Peries, Harry Pieris, and Ivan Peries. The minutes of the meeting, however, do not mention Keyt, Deraniyagala, Beling, and Manjusri, while Gabriel pointedly denied seeing Manjusri there.

Citing official records, Neville Weeraratne records that seven people attended the meeting: Ivan and Lester Peries, Aubrey Collette, George Claessen, Richard Gabriel, Harry Pieris, and Lionel Wendt.

The meeting formed a committee, consisting of Wendt, Ivan Peries, Collette, and Gabriel, while it “co-opted W. J. G. Beling, Ralph Claessen, Justin Daraniyagala, S. R. Kanakasabai, George Keyt, and Manjusri Thera.” Harry Pieries was appointed as Secretary, and George Claessen became Treasurer. The committee decreed that membership would be open to “all artists”, at a subscription of Rs. 5 a year “or part of a year.”

The 43 Group |

The meeting was an event of enormous importance, for the country and for the founders themselves. It proved to be the sequel to a struggle they had waged against the cultural establishment of the day. The latter revolved around the Ceylon Society of Arts, which had been founded by the government in 1887.

Established along the lines of the British Royal Academy, the Ceylon Society of Arts pandered to colonial middle-class tastes, and promoted a decidedly Academic approach to art. It not only decreed the artistic codes of the day, but also defined the dominant, prevalent artistic tastes. Naturally it came into conflict with those whose ideas of painting, and art in general, differed from theirs.

The founders of the 43 Group sought an artistic idiom far removed from the confines of the colonial middle-classes. Since most of them hailed from the latter group, their defiance stung the establishment. The leader and shaper of the Group, Lionel Wendt, took particular offence at what he saw as the imitativeness of the Society of Arts: “the Society,” he once observed, “exclusively follows the English School of water colour painters. It does not even attempt to profit by a study of the art of the modern European Schools.” One of the leaders of the Society, Mudliyar A. C. G. S. Amarasekara, shot back at Wendt, describing him, in jest, as “a modern Moses leading the elect out of the land of the Philistines.”

In their personal lives, too, the 43 Group reflected and reiterated their defiance. Though most of them hailed from a colonial middle-class and some, like Wendt and Deraniyagala, came from the upper echelons of this milieu, at school and elsewhere they hardly fitted in with the rest of their peers. While some achieved brilliant results at school, others became iconoclasts, preferring to spend time at libraries, learning on their own.

In certain cases, the institutions they found themselves in encouraged this habit; in other cases, they did not. George Keyt stood in the middle: at Trinity College, he had regularly flaunted his teachers’ orders, earning their ire and being punished, but he also benefited from the guidance and direction of Trinity’s greatest headmaster, A. G. Fraser, who encouraged his iconoclasm and allowed him to return to the library even after he had left school.

It could be argued that their family wealth and inheritance paradoxically liberated them from the conformist culture in which their peers and colleagues had ensconced themselves. It could also be argued that their wealth was their ultimate source of creativity, that when combined with their defiance of the views, tastes, and decrees of the establishment, they were able to gain the kind of agency to do what they wanted, as they willed, which others could not do.

Deraniyagala, for instance, who stood alongside Wendt and Harry Pieris as the wealthiest of the founders of the 43 Group, did not paint for profit: many of his works are unsigned. Far from exhibiting them abroad or even at home, he retreated to a world of his own, preferring to paint what he felt, thought, and perceived.

Yet if that defiance, and that refusal to conform, became their source of creativity, did the Group really realise their potential? In later years, the Group would be critiqued for not being in touch with the culture the society they sought to depict: for basically being too Anglicised, too Westernised, to be able to depict anything other than a superficial view of that culture.

Among the critics of the Group here were H. A. I. Goonetileke and Tissa Abeysekera. “The verve and enthusiasm of the forties,” Goonetileke observed, “petered out, perhaps because they were insufficiently grounded in the bedrock of the cultural patterns of Sri Lanka”, while the Group’s “choice of a medium which transcended language,” Abeysekera noted, remained “a handicap imposed upon them by socio-political circumstances.”

These lead one to all sorts of observations and conclusions, which may not necessarily align with each other. For instance, one can explain the 43 Group’s later failures in terms of the nature of the colonial elite. Despite their open and sincere defiance of that elite, it could plausibly be argued that, as Goonetileke pointed out, the enthusiasm that marked out their initial years could not survive the pressures of the postcolonial order: for all their rejection of the colonial elite, by birth and inheritance they remained moored to it.

The task of conveying that order and committing it to art would fall on a different generation of auteurs, hailing from a more bilingual milieu. This generation did not necessarily reject the 43 Group, at least not to the same extent that the Group rejected the Ceylon Society of Arts. But regardless of their sincerity in breaching the colonial order, it is possible that they were constrained by their backgrounds to fully break up that order. Yet it cannot be denied that, in openly defying the codes of their day, they paved the way for a revival of a more indigenised art. While recognising their limits, it is hence imperative that we also recognise this achievement, perhaps, the most seminal that the 43 Group made.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at [email protected].