Even though the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) finished as the single largest Tamil political party and won the second highest number of local councils nationally, the recent Local Authorities Elections marked a decisive low point in the party’s history.

Considering absolute figures – i.e. discounting the increase in total votes – the TNA polled a shattering 34 percent fewer votes across the north-east than it did in the General Election of 2015. Moreover, the party secured the outright majority in only 4 of the 41 councils it won.

It must be stated at the outset that a side-by-side comparison between the General Election of 2015 and the Local Authorities Elections of 2018 hides as much as it does reveal. The reasons for this are trivial. To begin with, the people in the northern and eastern provinces voted in a total of 27 members to Parliament in the General Election, whereas, this time they elected over 1,500 councilors to 80 different local authorities.

Moreover, this year’s local authorities elections was a fundamentally different game down to the changes made to the electoral system: in the north-east, as opposed to simply one electoral division for each of the local authorities there were 925 electoral wards. As such, a degree of vote scattering was always inevitable. Add the vastly varying voting motivations between the two elections, and a reasonable assessment becomes all the more elusive.

But certain post-election Tamil political narratives – purportedly based on the Local Authorities Elections 2018 results – need countering. Most of them concern the emergence of the Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF) led by Gajendrakumar Ponnambalam.

The TNPF, no doubt, performed significantly better this time than its previous electoral misadventures. In the Jaffna District, in particular, the party saw a four-fold vote increase against its general election performance and won the Point Pedro and Chavakacheri Town Councils.

A week after the election, Ponnambalam staked his claim for Tamil political leadership.

In an interview with Tamil language newspaper, Thinakkural, he interpreted the Tamil vote as reflecting an urgent need for changes in the upper echelons of Tamil political power. Ponnamblam argued that the Tamils have endorsed the TNPF as the clear alternative to the TNA.

But this is at best a puerile inference. The TNPF polled merely a quarter of the TNA’s votes. And the party was largely decimated in Tamil-majority areas outside of Jaffna, recording lower returns than even the Mahinda Rajapaksa-backed Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) in some cases.

Moreover, Douglas Devananda’s Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP) and V. Anandasangaree’s Tamil United Liberation (TULF) polled only 10,000 and 12,000 fewer votes respectively than the TNPF.

Deep discontent

Further, influential elements in the Tamil diaspora and sections of the local Tamil press, interpreted the TNA’s electoral fallout as the Tamils’ rejection of the party’s politics of ‘appeasement’. In other words, Tamils want a more radical, purer version of Tamil nationalism – supposedly projected by the likes of the TNPF.

There is, without doubt, a deep discontent against the TNA and its leadership. But the consequent political fragmentation suggests that the causes of such discontent lie outside of ideology. Tamil political parties across the ideological spectrum – from the TNPF to former Rajapaksa associates such as, the EPDP in Jaffna and the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (TMVP) in Batticaloa all shared the TNA’s cumulative loss. Further, independent groups foregrounding their campaign in anti-caste politics, social progress, and local development recorded impressive victories in pockets of the North. National parties, such as, the SLFP and the UNP also performed creditably well across the board – particularly, in previously war affected regions.

How then must we understand the TNA’s electoral decline?

First, the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi (ITAK) – the major constituent party in the TNA – is riddled with institutional deficiencies. The older generation of party loyalists who control decision-making have failed to empower the younger generation of leaders. Party discipline is non-existent and it singularly fails to speak in one unified voice. For the voter – particularly, the younger ones – the ITAK leadership appears immobile, indecisive, and worst of all, unreachable. This is a gap that the TNPF successfully filled in Jaffna.

Second, having fought and lost decisively against the TNA on ideological grounds in more than one election, Ponnambalam and his associates focused their campaigning elsewhere this time. An orchestrated media campaign targeted the TNA with false allegations of large-scale corruption. The charge was that TNA parliamentarians traded their support for Budget 2018 for a political bribe of 2 million rupees apiece from Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. This was virtually front page and prime time news across multiple Tamil language newspapers and television channels leading up to the election. A parallel social media campaign – channeled by a collection of Facebook profiles located locally and abroad (most of them with fake identification and profile pictures) – spewed hate and incited murder against senior TNA leaders.

Third, for established political parties so used to the Proportional Representation (PR) the Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP) would invariably take time adapting to. Newly delimited wards, for instance, threw up fresh challenges. A common feature in single member wards combining two or more villages was residents of each village simply voting for the party which appointed a popular candidate from their own community, often disregarding all other considerations. There are also credible suggestions that certain TNA leaders – past local councilors, present provincial councilors, and parliamentarians – muddled up their critical responsibility of candidate selection, going for personal favourites over the ward residents’ preferences.

There may, of course, be more to the story. But, to focus entirely on the TNA’s diminishing returns, however, would be to miss perhaps a far more significant reality.

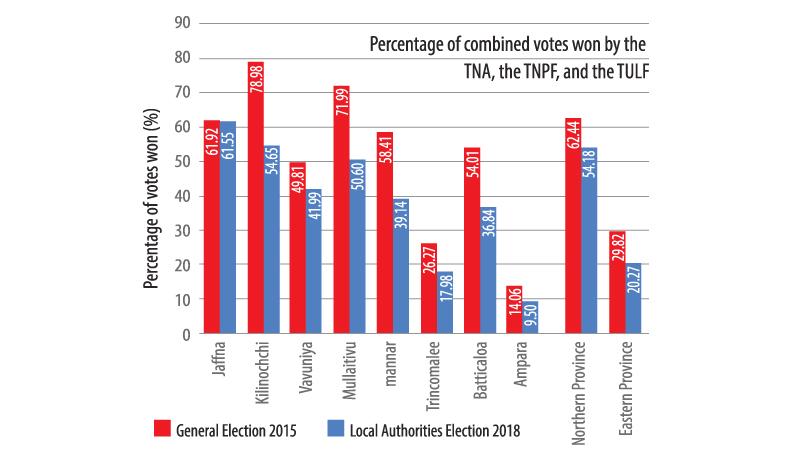

This message was not lost on the shrewdest Sri Lankan politician of his time: former President Mahinda Rajapaksa. In a press conference following his party’s resounding electoral victory, Rajapaksa pronounced that ‘Eelam has shrunk’. An analysis of the percentage drop in votes won by Tamil nationalist parties – the TNA, the TNPF, and the TULF – in the north-east between the General Election of 2015 and the Local Authorities Election of 2018 confirms Rajapaksa’s crude (and racist) quip. [See graph for details] In short, in each of Kilinochchi, Mannar, and Mullaitivu districts – or, in Vanni, to be concise – the share of votes won by Tamil nationalist parties fell by 20 percent or more. The figures for the Northern Province and the Eastern Province are 8 percent and 10 percent respectively.

The people that bore the brunt of the long war – trapped in mounting debt and severe economic depravity – are turning away from Tamil nationalist parties. National political parties with promises of employment and economic relief are waiting with their arms wide open. In the Mannar District, for instance, with an 80 percent Tamil population, the UNP won three out of the four Pradeshiya Sabhas. Only in Jaffna did the TNA’s losses, more or less, directly benefit the TNPF and the TULF. But even there, the EPDP saw a remarkable resurgence. In the final analysis, despite winning 5,000 fewer votes than the TNPF across the seventeen local authorities in Jaffna, the EPDP had secured more seats and won the two councils it did, much more convincingly. The EPDP’s gains in Jaffna are all the more noteworthy as it had neither state patronage as in the past, nor a strong supporting media campaign.

In Batticaloa, the TMVP led by Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan (alias Pillaiyan), who is also incidentally serving a prison term for involvement in murder, emerged as the second largest Tamil political party. A consensus emerged in the Tamil press that one of the primary factors behind its rise is Eastern Tamils’ resentment against the TNA offering the Eastern Province chief ministerial portfolio to the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, in the political reconfiguration that followed the defeat of Rajapaksa in January 2015. For the TNA leadership, at least, this was a goodwill gesture towards the Muslims in the hope of winning their support for the project of remerging the North-East.

The TMVP, on the other hand, centers its politics on the regional disparities between the north and the east, and opposes the North-East merger – a central Tamil nationalist demand – on those grounds.

The Local Authorities Elections results then, above all else, signify the diminishing power of Tamil nationalism as the great unifier and homogeniser of the Tamil people. Diverging regional concerns, religious differences, caste and class divisions, as well as economic disparities now animate Tamil politics more so than they have in the last 40 years.

But, for those in the South, to understand the foregoing analysis as a reassuring sign would be a grave mistake: further inaction on urgent Tamil political concerns – an acceptable political solution, demilitarisation, the release of political prisoners and land, and justice for war victims – would only intensify the fragmentation along the violent Tamil nationalist axis the TNPF represents. With access to diaspora funding and control of the Tamil media, the TNPF is more than capable of causing severe injury, to both, the Tamil youth in its ranks and the country at large. Preventing such decay rests on the TNA as much as it does on the Government.