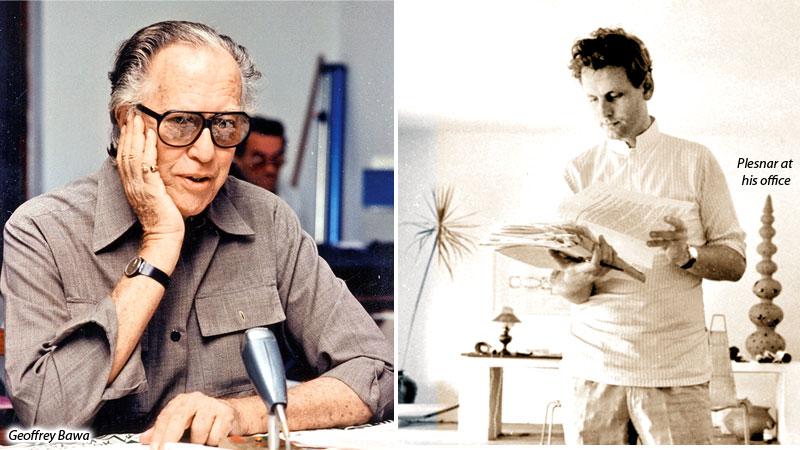

It is said that a prophet is seldom revered in his own country. This seems often to be true in Sri Lanka where those who aspire to greatness are often dragged down by their fellows. And so it is with Geoffrey Bawa, arguably the most significant architect of post-independence Sri Lanka, who is revered outside of Sri Lanka as one of the great Asian architects of the 20th C. And yet, a recent issue of the journal Domus has given a platform to those who seek to diminish his stature and attribute much of his achievement to Ulrik Plesner, a Danish architect who worked with Bawa from 1959 to 1966. To these people it is apparently unthinkable that a Sri Lankan could succeed on his own without a European puppeteer to pull his strings.

|

| Pic courtesy: nybooks.com |

What are the facts? Bawa returned to Colombo in 1957 having completed his architectural studies at the Architectural Association in London and became a partner in Edwards Reid and Begg (E.R. & B) alongside Jimmy Nilgiria and Valentine Gunasekara. He was already 38 years old and a qualified lawyer, but lacked experience of architectural practice. Plesner came to Ceylon at the beginning of 1958 and worked for a year in Kandy with Minnette de Silva. In 1959, at the age of 26, he moved to Colombo at Bawa’s invitation and joined E.R. & B., first as a freelancer, and then as an employee. Although he became a close associate and friend of Bawa he was never, in spite of his own claims to the contrary, a partner in the practice.

Youthful energy

Plesner was a talented architect and effective teacher, a charismatic figure bristling with ideas and full of youthful energy. Between 1960 and 1965 he and Bawa worked closely together in E.R. & B. and spent much of their free time in each-other’s company.

There were some projects that Plesner designed under his own aegis: for example, the annexe for Barbara Sansoni and the houses for Maurice Perera and Richard Pieris. There were others, few in number, which were tackled exclusively by him within E.R. & B.: for example, the warehouse for Lever Brothers and the offices for Bauer A.G. in Grandpass. But, the vast majority of work that passed through the office during this period involved both Bawa and Plesner, as well as, a talented team of assistants, though it is no longer possible to identify who did what, within any degree of certitude.

Thus, Plesner may well have taken a leading role in the design of projects such as the Ekala Industrial Estate, but, if the client is to be believed, had much less direct involvement with the Ena de Silva House. And, according to Thilo Hoffmann, client for the Polontalawa estate bungalow, its startlingly original concept, later claimed exclusively by Plesner, came from Bawa, while Plesner was responsible for the detailed design and supervision. Hoffmann wrote in 1998: “Both Geoffrey and Ulrik were involved. The first tying of strings and laying out of the different parts was done in my presence by Geoffery. Geoffrey provided the ideas, the inspiration, the basic concept and Ulrik later transformed them into reality.”

Too close

Bawa was by instinct a solitary individual, and, not the first or last time, he ended a relationship that was becoming too close for comfort. The two men parted acrimoniously in 1966 and Plesner returned to Europe. He was upset because Bawa had denied him the recognition that he believed to be his due, while Bawa thought that Plesner “had got too big for his boots”.

It may also be that he was jealous of Plesner’s popularity, of his wide circle of friends, of his many interests and his numerous extra-mural projects. Afterwards, they agreed to a strange division of the spoils which bore little resemblance to reality and which enabled Plesner to publish Polontalawa as his own, while Bawa could claim sole authorship of the Ena de Silva House.

The Bawa monograph that was published by Concept Media in Singapore in 1986 and came to be known as the “White Book” avoided all mention of Plesner and omitted buildings that had been ascribed to him under the ‘gentleman’s agreement’ such as, Polontalawa and the Bandarawela Chapel.

The latter was a particularly unfortunate omission because it was without doubt the product of genuine teamwork, involving the sculpture of Barbara Sansoni, the artistry of Laki Senanayake, the detailed design of Plesner and the conceptual thinking of Bawa.

In writing my book, “Bawa the Complete Works”, that appeared in 2002, I attempted to redress the balance and presented Bawa as the hub of a brilliant group of people that included, as well as Plesner, Bawa’s eventual partner Poologasundram, his team of talented assistants and his friends, Barbara Sansoni and Ena de Silva.

During 1998 I had consulted with Plesner at some length and prepared a draft text which he approved during a visit to my home in September 2001. I described how the two had worked closely together and how each had contributed in his different way to the projects that were built between 1959 and 1965. I also acknowledged that Bawa, who had very little hands-on experience before joining E.R. & B. in 1957, had benefited enormously from Plesner’s professionalism. At Plesner’s insistence I avoided trying to define their exact inputs to each project.

Alleged seduction

But Plesner wanted more and in 2012 he published his own memoir of his years in Ceylon under the title “In Situ”. In this strange book he boasted of his sexual exploits, including his alleged seduction of Minnette de Silva and his purchase of a concubine from a village headman, as well as, his role as a go-between in the sale of Israeli arms to Ceylon.

He also went to great lengths to deny that he had had any physical relationship with Bawa. A reviewer in the Architectural Review described him as “the playboy of the Eastern World” and recommended the book for light holiday reading.

But, without justification, Plesner also used the book to claim sole authorship of sixteen projects that he had worked on with Bawa, using drawings that, for the most part, had been drawn in the E.R. & B. office long after he had left Sri Lanka. He also boasted, hubristically, that “the only school of architecture that Geoffrey had was the one that I put him through” and that he had taught him all that he knew. These calumnies have now been broadcast in the December 2015 issue of the Domus journal which carried a whole supplement devoted to Plesner. A main essay adds to the Plesner mythology while offering little in the way of concrete evidence and is peppered with inaccuracies. In another essay, Bawa is referred to as “Plesner’s partner” in a bizarre inversion of their relative status!

Sadly, these calumnies have been further amplified at some length in a Japanese book by Iwamoto Hiromitsu that appeared in 2016. The book, although entitled “Bawa”, devotes an inordinate amount of space to Plesner and repeats many of the false claims of “In Situ”. Hiromitsu went to Jerusalem to interview Plesner shortly before he died.

Bawa, however, had been dead for more than 10 years and could no longer tell his side of the story, though Hiromitsu did not try to interview any of those close to Bawa who might have put him straight. His book borrows heavily from my own, though he never sought my permission and gives me scant acknowledgement.

Truth misrepresentations

These misrepresentations of the truth are now circulating freely on the information highways; for the sake of accurate historiography they should not be allowed to go unchallenged.

When Plesner left Ceylon there were those who predicted that Bawa would not survive without him. Paradoxically, the reverse was true. Bawa’s career ran on for another thirty years during which he produced a succession of masterpieces, while Plesner sank into the relative obscurity of a commercial practice in Israel.

His book reveals the extent to which he regarded his seven-year association with Bawa as having been the high point of his career, whereas, for Bawa it represented merely a short interlude in a long unfolding drama.

Bawa was by instinct a solitary individual, and, not the first or last time, he ended a relationship that was becoming too close for comfort. The two men parted acrimoniously in 1966 and Plesner returned to Europe. He was upset because Bawa had denied him the recognition that he believed to be his due, while Bawa thought that Plesner “had got too big for his boots”.

It may also be that he was jealous of Plesner’s popularity, of his wide circle of friends, of his many interests and his numerous extra-mural projects. Afterwards, they agreed to a strange division of the spoils which bore little resemblance to reality and which enabled Plesner to publish Polontalawa as his own, while Bawa could claim sole authorship of the Ena de Silva House.