Last week’s decision by the United States to pull out of the UN Human Rights Council created ripples in Sri Lanka where the parting words of America’s top diplomat that the Council was a “cesspool of political bias” resonated strongly with politicians and bureaucrats aligned with former President Mahinda Rajapaksa who waged pitched battles in Geneva from 2009-2014, claiming victimisation and similar partisan bias by member states.

For ruling party politicians, the US pull out seemed to indicate that the Government could be ‘off the hook’ with regard to further interventions on its human rights record in Geneva. Claims are being made that Sri Lanka should abandon the resolution it co-sponsored at the UNHRC in 2015 and 2017, since a main sponsor of the resolution and the protagonist of moves to hold Sri Lanka to account at the Council since 2012 had quit the proceedings.

For ruling party politicians, the US pull out seemed to indicate that the Government could be ‘off the hook’ with regard to further interventions on its human rights record in Geneva. Claims are being made that Sri Lanka should abandon the resolution it co-sponsored at the UNHRC in 2015 and 2017, since a main sponsor of the resolution and the protagonist of moves to hold Sri Lanka to account at the Council since 2012 had quit the proceedings.

Yet, celebration about being let off in Geneva may be premature, even though the dynamics at the UNHRC will be undeniably altered when Sri Lanka faces its next big reporting session on its rights record in 2019, and progress is measured on the country’s implementation of UNHRC Resolution 30/1 which was adopted by consensus in September 2015. The resolution calls on the Government of Sri Lanka to implement its transitional justice programs, including an Office of Missing Persons, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, an Office of Reparations and a special court to investigate and prosecute allegations of gross human rights violations occurring during the war.

The US pull out from the UNHRC makes little difference to Sri Lanka’s obligations under the 30/1 resolution, for a multiple reasons. Firstly, the resolutions of 2015 and 2017 were co-sponsored by Sri Lanka, meaning that the country accepted the spirit and content of the draft and agreed in principle to implementing its recommendations. Both resolutions were adopted by the entire Human Rights Council, approved unanimously. Since the Lankan Government did not enter into agreements on reconciliation and justice with the US Government in particular, the absence of the US from the Council makes no legal or institutional difference to the country’s obligations to implement provisions of the resolution, experts with knowledge of the workings of the Council opine.

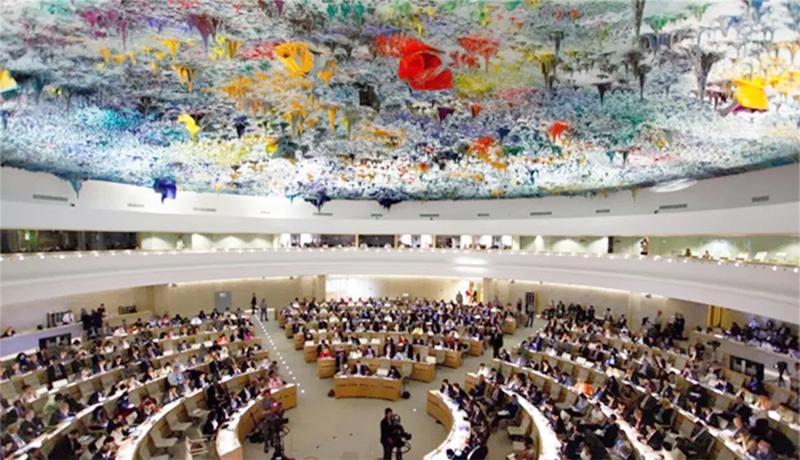

Secondly, the technical aspect of the US pull out is vital to understanding its impact on Sri Lanka and its continuing engagement with the UNHRC. Until last Tuesday, the US was one of 47 elected members of the UN Human Rights Council. The 47 members are elected for staggered three year terms, on a regional group basis. The UN General Assembly, comprising all 193 member states of the UN elect the member states who occupy the UNHRC’s 47 seats. Thirteen of these seats are reserved for African states, 13 for Asia, six for Eastern Europe, eight for Latin America and the Caribbean and seven for the Western European and others group. The 47 member states represented in the UN Human Rights Council have a vote each. Sri Lanka has never been a member of the UN Human Rights Council but has been an active participant in UNHRC sessions since 2009, lobbying countries to vote against US sponsored resolutions, making interventions and attending high level sessions. Several states that sponsored resolutions on Sri Lanka since 2012 at the UN Human Rights Council were not elected members. All this really means, is that these states, including Sri Lanka which is not an elected member, could not vote on the resolution.

Any one of the 193 member states of the UN General Assembly can sponsor, co-sponsor and support country specific resolutions or any other resolutions floated at the Human Rights Council in Geneva. In theory therefore, even though the US is no longer a member of the 47 member Council in Geneva, it can continue to act as a main sponsor of resolutions on Sri Lanka, together with the UK, Montenegro and Macedonia who form the ‘core group’ on resolutions drafted on the human rights situation in the island. Experts point out that Israel, whose alleged mistreatment by the Human Rights Council was one of the key causes of the US Government withdrawal from the body, regularly engages with the Council. Israel has even co-sponsored resolutions – including AHRC 30/1 on Sri Lanka and its 2017 follow up.

All this notwithstanding, international civil society actors say the US leaving the Council clearly has political significance, and badly weakens the ability of the US to engage with Sri Lanka and the rest of the Council in the coming months on the implementation of the 2015 and 2017 resolutions on promoting reconciliation and accountability in the island nation and any follow up actions in March 2019.

Many in the US Government hope to continue to influence the Government to fulfill its obligations to the Council and its own people, but experts warn that this will be harder from outside the Council.

“It is particularly damaging that the reasons the US Government gave for leaving the Human Rights Council – for being hypocritical and biased, echo so closely criticisms that the previous Sri Lankan Government and many Lankan politicians in opposition and in the current Government have made about the Council’s engagement with and resolutions on Sri Lanka,” said Alan Keenan, Sri Lanka Senior Analyst for the International Crisis Group.

“The US withdrawal will have lasting damage and will strengthen governments and politicians across the globe who prefer to be left to their own devices, even when this involves violating the fundamental rights of their own citizens,” Keenan said.

But the desire of politicians across party lines to pounce on the US pull out of the UNHRC as grounds to abandon the Resolution is both unfortunate and ultimately self-defeating. Realistically, the roll-out of reconciliation measures, including the release of private land held by the military, the efforts to repeal and replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act, the establishment of the OMP and the recent cabinet approval for an office of Reparations may all stem from the Government’s obligations under the UNHRC resolution. But there is no denying that the clamour for these measures began at home, in the war-devastated districts of the north and east, and in the south, where activists were hunted and intimidated for daring to call on the Government to uphold human rights. When the Government failed to hear domestic pleas for reform and reconciliation, the struggle to set Sri Lanka’s human rights record straight took an international turn.

The premise of the call for abandoning the UNHRC resolution in the wake of the US pull out from the Council itself is therefore flawed. After three decades of devastating civil conflict and 60 years of ethnic strife, the desire for reconciliation should not have to be internationally prescribed. Reconciliation ‘for our own sake’, was the promise of the Yahapalanaya Government in September 2015, when then Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera won accolades internationally for his humble and heartfelt intervention at the UNHRC in Geneva, where he unveiled a blueprint for reconciliation and justice that would help Sri Lanka reckon with its violent past.