In the works for three years, the proposed Counter Terrorism Act will come up before a Parliamentary Sectoral Oversight Committee (SOC) for the second time on Wednesday (6), where lawmakers could suggest further changes to the draft before the legislation can be approved for debate in the House.

The Bill will be taken up at the 20 member SOC on International Relations chaired by UNP MP Mayantha Dissanayake.

Committee Chairman Dissanayake has called for written submission from his members on the proposed Counter Terrorism legislation ahead of Wednesday’s meeting.

In April 2016, a committee was set up by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe to draft a legal framework for counter terrorism legislation that would repeal and replace the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). For nearly three years, the proposed legislation has been the subject of exhaustive deliberations, sweeping changes to the draft Bill to make it more human rights compliant and a spate of challenges in the Supreme Court when the proposed legislation was gazetted.

Late last year, the Supreme Court determined that portions of the Bill were inconsistent with the Constitution, ruling that unless those provisions were amended the Bill would require a two-thirds majority to be enacted into law.

Among the provisions the Supreme Court took issue with, was the decision of drafters of the proposed Counter Terrorism Act to do away with the death penalty as punishment for engaging in acts of terror. The apex court ruled that this exclusion was inconsistent with the country’s criminal laws, which still stipulates the death penalty as punishment for murder.

This exclusion was part of the effort to make the Counter Terrorism Bill more human rights compliant, officials with knowledge of the drafting process told the Sunday Observer.

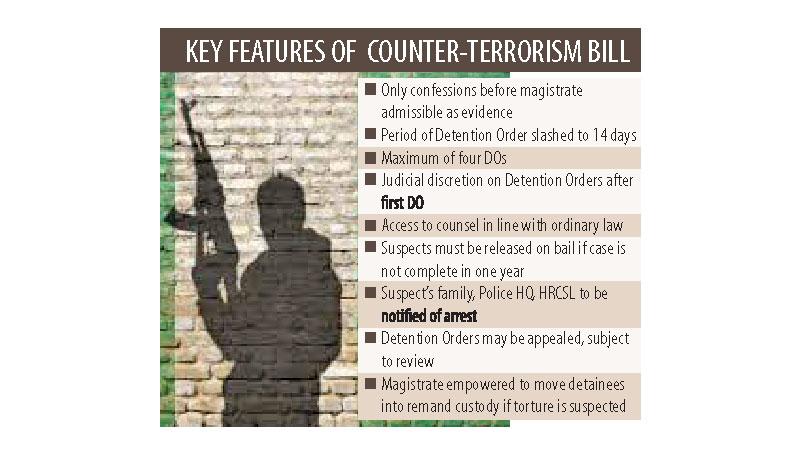

The draft counter terrorism legislation marks a sharp departure from the Prevention of Terrorism Act that has drawn the ire of human rights activists and lawyers for decades, because of its potential for overreach and abuse by the state. Key provisions of the PTA that infringe on civil liberties were not subject to judicial review for extended periods of time.

Over 40 years, the PTA often proved its detractors right, with successive governments using the legislation to crack down on journalists and dissidents and to intimidate and oppress the Tamil community living in the North and the East in particular. In the past decade alone, the PTA has been used to convict and sentence journalist J.S. Tissanayagam to 20 years in rigorous imprisonment, detain disappearances campaigners and human rights activists like Ruki Fernando.

Serious concern

But for many rights activists, the legislation proposed to repeal the PTA, has continued to cause serious concern.

A briefing note circulated by several civil society activists and organisations on the proposed counter-terror laws, raised objection to the definition of terrorism as contained in the Bill, claiming that citizens protesting against state involvement in water pollution (such as Rathupaswela), a state decision to dump garbage in their neighbourhood (such as post Meetotamulla), impact of development projects such as Hambantota development zones and Port City and citizens demanding the release of lands occupied by the military could be treated as ‘offences of terrorism’.

But some experts highlighted that the definition of terrorist intention by and large corresponds to that currently under negotiation internationally. Section 3(2) of the draft Counter Terrorism Act which lists acts which are criminalised, specifies that they must be carried out with the intention of committing an act of terrorism as defined in Section 3(1). Section 3(3) also specifies an exception for acts that may fall within the citizens’ fundamental rights – such as the freedom of assembly. etc.

The country’s chequered history with the PTA has also driven drafters of the new law to include a specific provision into the Counter Terrorism Bill, which stipulates that however serious the crime or its complexity, procedures permitted under the CTA cannot be used to investigate offences that fall within the ambit of the country’s other laws

Central Data Base

Civil society representatives also raised objections to the Central Data Base for arrests and detention provided for in the proposed Counter Terrorism Act. The draft legislation provides the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) access from the outset and ensures every arrest and detention carried out under the law is logged at every stage.

Activists said that the database could result in information being shared between state institutions and international agencies, with the potential for those merely detained or charged being adversely affected in terms of reputation and freedom of movement.

But within civil society itself, there has been praise for the CTA proposal to set up this database. “This provision is an improvement from the PTA. Maintaining a Data Base Register of this nature under the proposed CTA ensures accurate information concerning a person’s arrest, detention etc. is communicated to HRCSL,” the Centre for Policy Alternatives notes on its report on the proposed Counter Terrorism Act released late last year.

In fact everything is documented from the moment of detention to prevent people from disappearing, an official familiar with the drafting process said. In the past, there were allegations of people disappearing, after being supposedly arrested under the PTA, these officials explained. With the central database in place, all arrests under the proposed CTA will be documented from the moment of detention and HRCSL will have full access to the information, resulting in safeguards for the suspects.

The CPA’s comprehensive review of the proposed Counter Terror legislation finds several improvements on the PTA in the draft, and in many cases has found provisions in the bill to be in line with international law and best practices.

The CPA report found that provisions that stipulate arrest with privacy, medical examination of suspects, notification of arrests, the board of review for detention orders, the entitlement of the magistrate to visit any place of detention and the dramatic reduction of the maximum period of detention to eight weeks were significant improvements on the PTA.

The power of the magistrate to order a forensic medical examination when there is reason to believe a suspect may have been subject to torture, is a welcome provision, the CPA report on the Counter Terrorism Bill said. The provision is in line with Article 11 of the Sri Lankan constitution and Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the CPA said in its report.

The report also contends that some provisions of the Bill lists “vague and wide” offences that allow potential for abuse, and critiques the draft legislation for giving far-reaching powers to the police, armed forces and coast guards to make arrests,

One provision in the Counter Terrorism Bill that causes consternation, and is also dealt with at length in the CPA report is Clause 81 of the Counter Terrorism Bill which deals with proscription orders (PO) on organisations.

POs

POs can be issued against organisations engaging in any activities which are offences under the proposed CTA or on the grounds of national security. According to the CPA report, the PO regime goes further than the Counter Terrorism Bill’s specified offences and could have an impact of impairing fundamental rights of persons and other liberties.

“The wording of sub clause (1) which states “acting in a manner prejudicial to the national security of Sri Lanka” is over broad and can be abused.

This provision can be misused in a manner to curtail dissent and proscribe organisations that advocate for legitimate human rights concerns,” the CPA said in its report.

The CPA report suggests a remedy to this clause to address the concerns, by inserting the word “wrongful”before the word “manner” in the provision. Civil society activists are concerned that there was no avenue to challenge the move before an order is issues, and an appeal to the Court of Appeal is possible only after the order is made and the detrimental impact has been caused.

However, legal experts familiar with the drafting of the Bill said steps taken under Clause 81 is also subject to judicial review, and moves to proscribe may be challenged in the Supreme Court through a fundamental rights petition citing imminent infringement or through the application for a writ in the Court of Appeal.

While it might even be a case of stating the obvious, because of the monumental abuse of the PTA over four decades, the drafters also included Section 96 in the proposed Counter Terrorism Act, reiterating that were actions taken by virtue of powers granted by the law were subject to judicial review, by means of fundamental rights or writ application against any regulation or directive contained in the Act.

While civil society organisations are crying foul about the Bill being draconian, ironically, a second set of detractors have diametrically opposite reservations about the Counter Terrorism Bill – that it does not grant law enforcement agencies enough sweeping powers to crackdown on terrorism and terrorism related offences.

The pro-Mahinda Rajapaksa faction of the UPFA and more hawkish sections of the ruling UNF administration have opposed the Counter Terrorism Bill on the grounds that it will be ‘too soft’ on terror offenders.

Some members of the pre-October 26, 2018 Cabinet even vowed to move amendments to the Bill in Committee Stage before voting for the legislation. The threat has alarmed human rights lawyers, who explain that amendments at the Committee Stage in Parliament will not be subject to judicial review, and cannot be challenged in court before the Bill is voted and enacted into law.

While the Bill contains some valid reasons for concern on the part of activists, academics and lawyers worry that tearing down the draft legislation could pave the way for the retention of the PTA in Sri Lanka’s statute books, a horrifying prospect, given the inherent nature of the alternative Government waiting in the wings in an election year.

Lecturer in Public Law, Edinburgh Law School and Director, Edinburgh Centre for Constitutional Law, Dr Asanga Welikala believes the proposed Counter Terrorism Bill will work with a few “tweaks” to the current draft.

“The Counter Terrorism Bill, with some crucial tweaks, is a more than defensible replacement for the PTA. Opposing it on naively idealistic grounds is self-defeating, and will deprive human rights defenders of any influence over the legislation, and risk the opportunity to get the PTA repealed,” Dr Welikala tweeted last week.