Exactly a week from today, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) is set to hold a huge rally in the central city of Kandy, where expectations are that former President Mahinda Rajapaksa will formally take over the reins of the fledgling political party that swept the February 2018 local authorities election. August 11 is also when the SLPP rank and file strongly believe the former President will finally anoint the party’s presidential hopeful. Most of the party believes this candidate should be the man who functioned as Secretary to the Ministry of Defence throughout his brother’s decade-long presidency, Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Since his brother’s fall from power in 2015, the former Defence Secretary has been under investigation in a slew of cases, ranging from money laundering and misappropriation to his alleged role in the abduction and attacks on journalists. In September 2018, he was served indictments as the first accused in a massive corruption scandal known as the D.A. Rajapaksa museum case. Rajapaksa is accused of having misappropriated monies from the Land Reclamation and Development Board to the tune of Rs 33 million to build a memorial for his deceased parents in Medamulana in 2013. In 2015, Rajapaksa successfully petitioned the Supreme Court for a stay order against his arrest in the investigation into the 2006 MiG-27 procurement by the Sri Lanka Air Force. He remains a suspect in the Avant Garde floating armoury case and a person of interest in the abduction and torture of journalist Keith Noyahr and the disappearance of cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda.

In March 2017, the Criminal Investigation Department told the Mount Lavinia Magistrate’s Court that they had uncovered evidence that the former Defence Secretary had controlled a death squad allegedly involved in the murder of former Sunday Leader Editor Lasantha Wickrematunge. Gotabaya Rajapaksa has denied the allegation. CID investigations have found that the military intelligence unit known as the Tripoli Platoon (because it operated out of the Tripoli army camp in Maradana) has been implicated in the attacks against several journalists including Wickrematunge, Noyhar, Upali Tennakoon and Namal Perera.

If Gotabaya Rajapaksa contests the presidency later this year, he will become Sri Lanka’s first presidential candidate to stand for election to the highest office of the land while being on trial for corruption in the Permanent High Court in Colombo. With Lasantha Wickrematunge’s 28 year old daughter Ahimsa filing a civil action in California, accusing Rajapaksa of instigating and ordering the extra-judicial killing of her father, he will also go down in Sri Lankan election history as the first candidate to contest the presidency while being on trial for murder in a foreign jurisdiction.

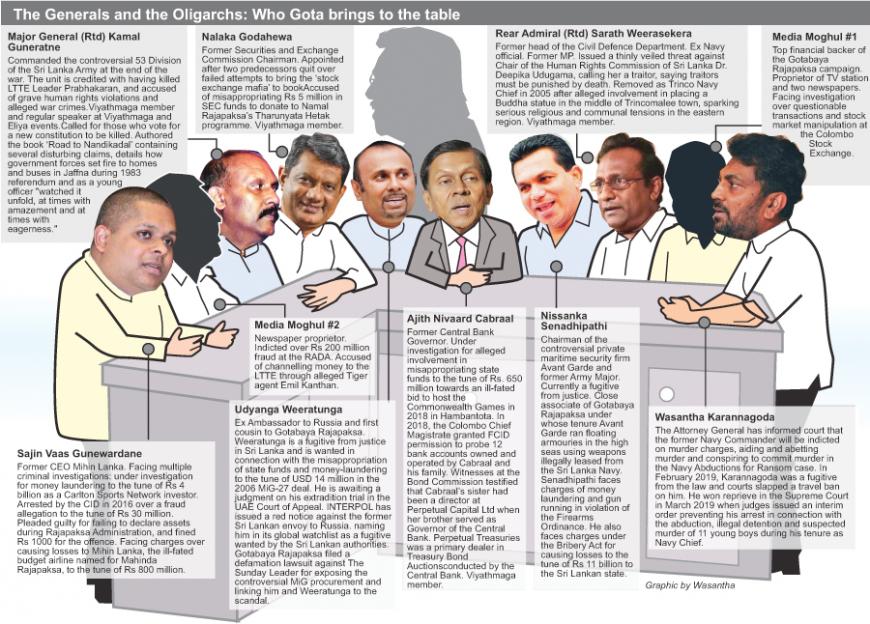

All this notwithstanding, or perhaps for those very reasons, since 2017, the Gotabaya 2020 campaign team has been mobilising in the wings. Rajapaksa chairs Viyathmaga, the self-styled grouping of ‘intellectual technocrats’ – high net worth businessmen, academics and young entrepreneurs with a strong belief in the ‘benevolent despot’ model of governance and economic prosperity. Rajapaksa has also given leadership to Eliya (light), a civil society movement that holds regular meetings at which the former Defence Secretary and ex-military personnel loyal to him are regular keynote speakers. Together, these are Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s team of generals and oligarchs, the men who are almost assured of seats at the table if their leader ascends the presidency.

Within the SLPP, Gotabaya Rajapaksa continues to attract the biggest donors and easily surpasses all other would-be presidential aspirants in terms of monetary resources and manpower. Team Gotabaya believes its grassroots electoral machinery – largely made up of ex-servicemen in small villages around the country – is in order. Propaganda remains the former Defence Secretary’s best play – the country’s most creative advertising agency is run by one of Rajapaksa’s biggest backers, media moghul Dilith Jayaweera.

All this hectic early preparation and campaign organisation has automatically propelled Gotabaya Rajapaksa to the front of the SLPP pack of presidential aspirants. But for his own reasons, Mahinda Rajapaksa has fought shy of confirming his younger sibling and ex defence secretary will be his party’s presidential candidate in 2019. Under the provisions of the 19th Amendment, persons under 35 years of age at the time of the election are barred from contesting the presidency. Hambantota District MP Namal Rajapaksa, the former President’s eldest son, is just shy of the constitutionally prescribed age limit this year. Any presidential aspirations on Namal Rajapaksa’s part will have to wait five years. As previously discussed in these columns, and speculated by multiple political analysts, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s ideal candidate for the 2019 election must be a place-holder for his son, the true heir to his political legacy. According to sources close to the former President, Mahinda Rajapaksa remains unconvinced that Gotabaya Rajapaksa will be an effective ‘regent’. Over the past four years, Gotabaya has charted his own political course and gathered his own band of acolytes and advisors – and none of them are career politicians. If Gotabaya Rajapaksa ascends the presidency, his immediate family takes over the mantle of first family and his coterie of businessmen and military commanders will become key influencers and decision makers within the SLPP. Gotabaya Rajapaksa himself is a former soldier. The ex-servicemen surrounding his campaign now stand accused of some of the worst war-time atrocities. Their statements and conduct as new entrants into the realm of civilian affairs have only given rise to fears that their political solutions will be no less brutal than the strategies adopted in the battlefields. Relations between these elements of the Gotabaya campaign and the Mahinda Rajapaksa faction of the SLPP remain tense. The Gota faction needs Mahinda Rajapaksa to endorse its candidate before campaigning begins officially, but they are clear-eyed about their preferred vision for the political future. In their calculation, Mahinda Rajapaksa – the authoritarian president who presided over one of the country’s bleakest eras for democracy and freedom – is too soft, too indisciplined, too much of a democrat.

For some reason, this phenomenon is giving Mahinda Rajapaksa pause.

In 2018, political scientist Jayadeva Uyangoda wrote that the entry of Gotabaya and his cabal into the sphere of politics and governance has the potential to reshape civil-military relations that Sri Lanka’s democracy has maintained since the post-independence period. Uyangoda calls this a ‘bi-partisan consensus’ between the country’s two largest political parties, an unwritten pact that the military will always remain within strong civilian control. This consensus, Uyangoda argues, allowed democracy to survive in Sri Lanka through a four decade period of two civil wars, starting with the youth insurgency in 1971.

The sentiments are being echoed by party seniors. Kumar Welgama, a SLFP stalwart for 38 years and a staunch loyalist of the former President, threw in the towel last month. He met SLPP frontliner and main organiser Basil Rajapaksa personally, to tell him that he would not back the Pohottuwa campaign if the party chose Gotabaya Rajapaksa as its presidential candidate. Other rumblings continue, although the Rajapaksa family is convinced that once Mahinda Rajapaksa makes his decision known, other constituent parties will fall in line. For months now, Wimal Weerawansa’s NFF and Udaya Gammanpila’s Pivithuru Hela Urumaya have strongly backed the Gotabaya faction within the SLPP. The party’s young backbench MPs largely support the former Defence Secretary’s candidacy. The resistance to Gota 2020 has emerged from within the traditional allies of the centre left party – particularly from the New Left Front and the MEP. Seasoned political campaigners are sniffing change in the air and remain fearful that Gotabaya’s ascent to elected political power, the era of the career politician, will give way to a new political epoch in which the generals and the oligarchs will hold sway. When the SLPP entered into 10 agreements with political parties not represented in Parliament last month, several senior politicians aligned to Mahinda Rajapaksa, including Dinesh Gunewardane, were absent from the ceremony.

The persistent resistance has given rise to fears that the August 11 rally will not materialise with the anointing of a SLPP candidate. When realisation began to dawn late last week, it caused serious panic in the Gotabaya campaign. Compounding questions about the multiple corruption investigations was the issue of the former Defence Secretary’s US citizenship, which barred him from contesting for public office in Sri Lanka. SLPP seniors worried that if his citizenship status remained unclear at the time of nominations, his candidacy could be compromised straight out of the gate, jeopardising the party’s chances at the election. With Mahinda Rajapaksa seemingly still skittish about announcing the nomination, the Gota 2020 campaign went into overdrive last week to prove that the citizenship question was no longer a concern for the former Defence Secretary.

A forged document surfaced first last Tuesday, purporting to show that the former Defence Secretary had obtained his loss of citizenship certificate from the US State Department. Widely debunked as a bad Photoshop job on a Wikipedia sample of the loss of citizenship certificate, questions were raised about who leaked the badly edited forgery. Several daily newspapers led with the report about the fake document being circulated, causing serious embarrassment to the Gotabaya campaign. On Thursday, media reports indicated another leak, this time purporting to show Rajapaksa’s authentic loss of citizenship certificate, allegedly authenticated by the Chief Consular Officer at the US Embassy in Colombo. The next day, newspapers aligned with the former defence secretary also published a photograph of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s purportedly cancelled US passport.

For the rank and file of the SLPP, last week’s revelations may have allayed fears about the citizenship question.

For rights activists, journalists and moderates, the Gotabaya political phenomenon raises the spectre of white-van abductions, brutal crackdowns on civilian dissent and vicious communal tensions. But what keeps party seniors up at night are very different fears. With his generals and oligarchs in charge, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency could transform post-independence politics in an unrecognisable way. In a kitchen cabinet where the Sarath Weerasekeras and Kamal Guneratnes call the shots, the future is bleak for the Old Guard, protected and carefully nurtured by SLFP leaders including Mahinda Rajapaksa over decades. Whispers abound in SLFP circles that the prospect of a Gota candidacy could drive party seniors to an alliance led by the UNP, which is likely, in the final analysis to field a common candidate.

With a week to go and his struggle to renounce US citizenship allegedly over, the former President is under crushing pressure to name Gotabaya Rajapaksa as his party’s presidential candidate for the 2019 poll.

Mahinda Rajapaksa remains in an unenviable position – torn between anointing his brother, the man he knows may have hastened his own political defeat in 2015, ensuring the path is primed for his son, and ensuring that his party does not implode, jeopardising a presidential campaign for the second time in five years.