The following are excerpts from a keynote speech made by Women and Media Collective Executive Director Dr. Sepali Kottegoda, on International Women’s Day in 2017, at a discussion titled “Bringing Unpaid Care Work from the Private to Public Arena –Through the ‘Empowerment’ Looking Glass”:

The notion of women as mothers, carers and the primary person responsible for the well-being of the family runs through all spheres which effectively is the factor that holds women back.

Does ‘caring’ work?

The concept of ‘care’ is not necessarily associated with ‘work’. ‘Care’ is often conflated with notions of altruism or unselfishness and self sacrifice rooted in the family and related to a system of a gender division of labour where women are seen to play the key role as care givers.

In mainstream economics as well as in social perceptions of persons, ‘work’ is understood as activity that brings in monetary income; ‘having a job’, ‘looking for or engaged in employment’.

The need to recognize unpaid care work for the economic value it contributes to a country first came into focus in 1980.

Kate Young and others looked at women’s labour in its different aspects and the ways in which the global capitalist market honed in on the critical importance of women’s labour to the production of goods but without recognition of the value of women’s reproductive roles . Marilyn Waring questioned why women’s work in the home is not counted as contributing to the national economies.

Unpaid, care work

‘Unpaid’ means that the person doing the activity does not receive a wage and that the work, because it falls outside the production boundary in the System of National Accounts, is not counted in GDP calculations.

The total working age population in Sri Lanka 15 years and above: 15.2 million; the sex disaggregated population 15 years and above comprises 8.2 million women and 7.0 million men. The working age population is further enumerated as Economically Active and Economically Inactive to estimate the proportion of those who form the labour force and those outside the labour force.

Economically Active Population: All persons who are/were defined as ‘employed’ or ‘unemployed’ during the reference period of the survey.

Economically Inactive Population: All persons who neither worked nor were available/looking for work during the reference period.

The Labour Force Participation Rate (LFR) is defined as the percentage of the current ‘economically active’ population (the labour force) to the total working age population.

The population recorded as ‘not looking for work’ during the reference period are categorised as ‘not in the labour force’ or Economically Inactive.

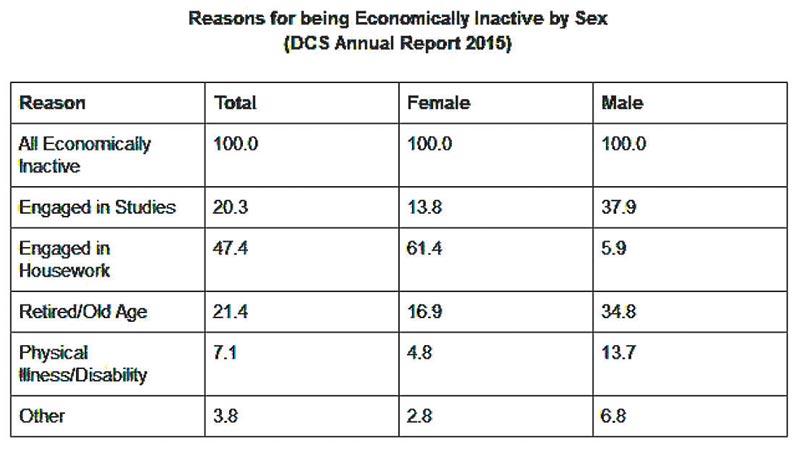

The DCS (2015) estimates that out of a total of 7.0 million persons categorised as being ‘outside the labour force’, i.e. economically inactive, 5.2 million or 74.8% are women and 1.7 million or 25.2% are men.

Engaged in housework

This phrase often includes what are termed ‘reproductive activities’ i.e. preparing food, washing, cleaning, caring for the young, and the old members of the household.

These are activities that, if carried out by someone hired for the purpose, would be valued in terms of a wage.

The person who is paid wages for household care work is: counted as being ‘in the labour force’, categorised as being engaged in ‘productive’ work.

Enumerating unpaid care work

This is critical to understand the role that women play in contributing not only to the ‘social and economic’ well-being of the family but also to the national economy.

Economic value and public policy

For households and families to be sustained on a daily basis, women provide their labour and time working on average 15-18 hours per day. The challenge to economists as well as to gender equality advocates and policy makers is the fact that Care activities are explicitly excluded from estimates of a country’s Gross Domestic Product .

In recent conversations with women community organisers on understanding unpaid care work, they observed that :

If a woman has a job/is employed, there are times when men or other household members would share some elements of housework because they understood that she was ‘tired after working’.

But, if the woman is a full time housewife, she is not seen to bring money into the household, and such consideration or support was markedly absent.

A recent study in Bangladesh has brought this issue into focus and holds the promise of the adoption of similar methodologies in Sri Lanka. Bangladesh carried out a comprehensive survey on unpaid care work to, ‘estimate the cost of unaccounted work performed by women and connect the findings with mainstream national accounting’.

The basic methodology aim was to: estimate time spent by both men and women for daily activities, estimate the economic value of women’s unaccounted activities, make recommendations for capturing women’s contribution to the economy with a view to improving women’s status in family and society.

The study found that ‘Based on replacement cost method, the estimated value of women’s unpaid work was equivalent to 76.8% of GDP.

The Bangladesh study shows that using, developing and focusing methodology is essential for better data collection on women’s and men’s socio-economic roles for more focused economic policy.

Reproductive is productive

Assessing the economic contribution of women must necessarily include work that is done for monetary remuneration as well as work done in the ‘reproductive’ sphere without which no household functions, and no workers would be able to engage in ‘productive’ work.

It calls for government and other social and economic actors to put into effect comprehensive measures, regulations and policies that would provide national level data on the value of unpaid care work, invest in safe childcare facilities accessible to women and provide incentives for employers to encourage men to share in household care work with women.

A century ago, Engels argued that women’s liberation was only possible if they move out of the oppression of the home into the labour force.

Ongoing research and analysis of unpaid care work, however, brings into focus the underlying principles of patriarchy which bind together social norms, unequal power and the labour market that continues to oppress women through the burden of housework.

Courtesy: Women and Media Collective