For ten years without war, there should have been something better to show. Half of the decade saw rulers trying to undo the gains that others made in the other half.

The good news is that the light is seen at the end of the tunnel. The policy confusion and missteps of the last government has led to a transition that is tougher than most, however. Vision is called for, at this conjuncture when the nation has taken the correct path at the crossroads.

Crass anti nationalism was made a way of life by the former government, and Volkswagens were to replace paddy fields. The Volkswagens didn’t materialize either, as we know all too well.

Part of the anti national tendency was the trend to privatize, or sell off the family jewels to foreigners.

So de-nationalization became a concomitant or crass anti nationalism.

Run to seed

State enterprises were allowed to run to seed. In 2018, SOEs made record losses, a fact acknowledged by the then Finance Minister. But there were no correctives put in place.

Though it was never stated polity, the strategy was to let state enterprises decay, so that they could be sold by auction at a future date.

This brings us to the the clamour today for re nationalization of state enterprises, beginning with the Kantale sugar factory.

The newly appointed Governor of the Eastern Province, Anuradha Yahampath has reportedly said that the Kantale sugar factory will resume operations under her watch.

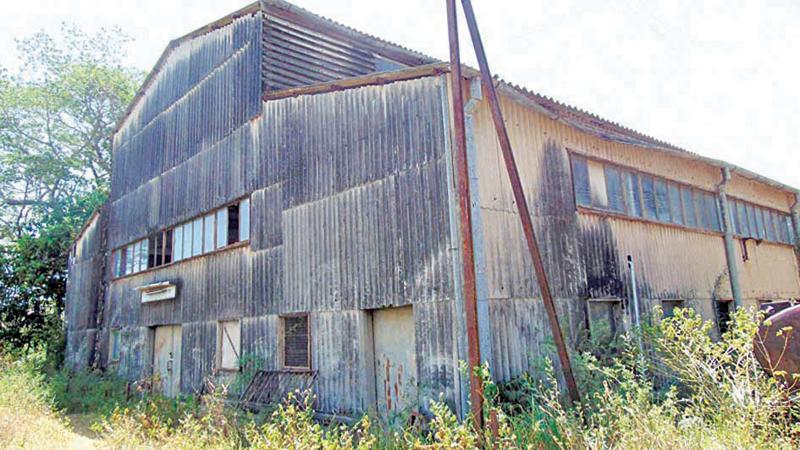

Meanwhile, there has been ferment in social media led campaigns to ‘nationalize’ the Kantale sugar factory, which already belongs to the State, and is now in disrepair.

The idea is for the State to step in and take over SOEs or state owned enterprises that went to seed or were deliberately run down, after the economy was liberalized.

The Kantale sugar factory was an outright gift by the Czechoslovakian government in the 1960s.It was privatized in 1994, but soon the move led to conflicts between the new owners and factory labour groups, leading to the closure of the factory soon after.

In the 1990s Thulhiriya and Pugoda textile mills were also privatized, along with a host of other state owned enterprises such as Lanka Loha.

Vijaya, Noorani and Shaw tile companies which were owned by the Government were handed over to private Management, apparently through private arrangements that saw no transparency whatsoever.

Privatization did not deliver desired results in most of the early instances of the so called peopolization policy in the early 1990s, which eventually led to entire industrial sectors which offered thousands of employment opportunities to Sri Lankans, going completely defunct.

Labour disputes

The state found that even though state enterprises were running at huge losses, a government that was bad at managing, was worse at transactions. A whole slew of privatizations were botched when there was no proper retrenchment of labour undertaken before the privatization process began.

Kantale Sugar, Ceylon Oxygen, etc were all examples of such bad policy. New private managers were not adept at dealing with labour disputes that arose after divestiture, and the privatized entities soon went to seed.

This was with the exception of some privatizations such as that of the Oils and Fats Corporation, which was sold to a subsidiary company of Prima.

A state that doesn’t know how to manage, or to privatize, was doomed, and now we rely on imports for most essentials such as paper, milk food, etc and that’s ludicrous because local production would have not just met the needs of our people, but left room for exports too.

The privatization of the Ceylon Ceramics Corporation for instance, led to the closure of mines for raw materials such as feldspar, in the bargain.

Though privatization got loss making SEOs off the hands of the state, the entire privatization process in this country has largely been a colossal misadventure, as the above examples would indicate.

The result is that the country that had to endure losses by state enterprises, now having to face a situation of increased loss of employment as a result of privatizations, coupled with a drain on foreign exchange, as local production of commodities drastically declined.

Revived

The call now is for some of these State owned entities to be revived, beginning from the Kantale sugar factory. However, the systematic running to seed of state owned enterprises has seen to it that the state is already saddled with SOEs making massive losses, amounting to several billions of rupees. The losses reached a record high in 2018, for instance.

Adding a sugar factory and other neglected entities to this loss making portfolio, may be dreaded by economists who have an eye on fiscal discipline.

Therefore, it is obvious that there is a need to look at SOEs in an entirely different manner, if the crass anti national privatizations of the last three decades are to be reversed in any effective way that is gainful to the state. The old paradigm of state owned enterprises offering job security and welfare to a workforce while being loss making, is so much nonsense.

Sri Lanka cannot consider going back to that era of lotus eating abandon. But a new government was elected to device ways of kick starting a production economy, and the industrial and agricultural sectors should be rejuvenated either through profitable nationalization, or effective privatization.

The issue of the Kantale sugar factory should be looked at in this context. Let’s not sugar coat this. Can the state afford to resurrect Kantale sugar, and manage it as a profitable entity, or will the state be saddled with a white elephant entity that is a showpiece national industry that provides jobs, and just about nothing else?

It’s fine to think of Kantale sugar, as long as the entire SOE sector is re-envisioned.

It’s not a secret that a major portion of the losses to the State come from the CEB, Ceylon Petroleum, and Lanka Sathosa, etc, out of which some have been considered strategically important SOEs which have to be subsidized by the State as a matter of necessity.

Trusted delivery

But, the strategically important sector, so called, is causing a drain on the Exchequer that makes it impossible for the entire state owned enterprise apparatus to restructure as collective profit making entities.

So what’s the answer? It’s either to revive loss making state enterprises with proper Management and talent, or to forget the dream of nationalizing Kantale, etc altogether.

If any of that cannot be done, at least revive those industries and hand them over to proper private management under proper process, that can be trusted to deliver.

For this to happen, it seems essential that some state entities be completely reorganized first, so that any subsequent privatization is not a disaster such as the so called peopolisation of Kantale sugar in 1994.

It is of course the stated policy of the Government to desist from divestitures of state owned enterprises. Well and good, and that leaves no choice but to run efficient SOEs.

It can only be done by ensuring efficient Management carried out by a pool of chosen folk, who have the drive, energy and talent to deliver results.

Such a pool of talent has to be thoughtfully picked, without fear or favour, and without any political patronage in the equation.

But there are other factors too. Lee Kwan Yew, the wizard who envisioned modern Singapore, said that if you pay peanuts you get monkeys.

Real talent has to be attracted to state owned enterprises by simply being competitive in the area of remuneration. Pay them well, and hopefully they will deliver.

Of course, not necessarily, some may say. Sometimes, those who are paid well would rest on their remuneration package, because they cannot be sacked by any shareholders.

State owned enterprises therefore have to be given over to great talent, men and women who also have a sense of mission. The people at the helm of SEOs must share in the concept of development.

But these sentiments can be mere platitudes, because state enterprises are still prone to fail even if all of these lofty ideals are there in the first place. So take it step by step.

Have the talent in place first. If that does not deliver, there has to be course correction. Our decade of anti-national wanton mismanagement has to end, one way or the other, and that’s what is important.