Last month the Sunday Observer initiated a column to promote diverse forms of indigenous knowledge and traditions of Sri Lanka. As part of that endeavour, we feature this week an interview with Dr. B. D.Nandadeva, Chairman of the Panel for Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) of the Sri Lanka Arts Council (SLAC), from 2016 to 2018 and appointed by the National Heritage Division of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs early this year to write the nomination on Dumbara Rata Mats for UNESCO’s 2021 Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity that was adopted in 2018.

He was previously appointed in 2017 by the National Heritage Division of the Ministry of Education to write the nomination to inscribe Traditional String Puppet Drama of Sri Lanka on the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Dr.Nandadeva has served as Prof and head of the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Kelaniya.

Excerpts of the interview conducted by Frances Bulathsinghala

Q: Could you begin by listing out the current categories of ICH of Sri Lanka, as well as those which had died out with time due to modernity?

A. Let’s begin with the definition, description, and categorisation of ICH as spelt out in the UNESCO (2003) Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accordingly, ICH means “… the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognise as part of their cultural heritage”. The definition further describes that ICH is “… transmitted from generation to generation” and “is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity”.

The UNESCO categorises ICH as being manifested in five domains namely; “(a) oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage; (b) performing arts; (c) social practices, rituals and festive events; (d) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; and (e) traditional craftsmanship.”

This shows that the scope of ICH is much similar to those of the two inter-related related disciplines, Cultural Anthropology and Folklore that we are already familiar with.

Practices of ICH are not static. As the UNESCO description states, ICH elements are constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment as human societies evolve. It is also possible that certain ICH practices that fail to adopt to social change, or that are rejected by it will just disappear, while new ICH practices that are necessitated by such social change come into existence.

There are several examples of Sri Lankan ICH practices that have died out within the times of our own generation. To name a few: dozens of beliefs and rituals associated with all stages of rice cultivation, certain forms of healing rituals, traditional knowledge of chena cultivation, certain forms of home remedies for simple ailments such as ‘kem-krama’ and ‘ath-beheth’, occult sciences such as ‘yantara-mantara-gurukam’, and rituals associated with pregnancy and child birth.

Q: You have been the head of the Department of Fine Arts, University of Kelaniya for several years. Could you comment on the insight, understanding and commitment to the use, preservation and protection of the intangible indigenous heritage knowledge of Sri Lanka by Fine Arts students?

A. Yes, those young undergraduates are indeed very keen in the preservation and protection of the ICH of the country.

They learn folk arts of Sri Lanka; Kandyan, Low-country and Sabaragmuwa dance traditions; and folk music; and some selected ritual forms. With youthfulness and energy, they learn those subjects with much enthusiasm.

They show a great deal of commitment in the preservation of these art forms. As the majority of them end up as school teachers, I am sure they take these messages to schoolchildren, the future generation of caretakers of the intangible heritage of the country.

Q: Could you comment on our lost heritage of the Gurukula education system?

A.Gurukula system was a system of education and training in which the knowledge and skills of arts, crafts, or other trades such as the performance of rituals, or the practice of medicine were passed down from parents to children, thus producing the next generation of practitioners of that art, craft or the trade. The system, which was also an essential part of the Sinhala caste system, collapsed with the fall of the Kandyan kingdom, and was replaced by Western-style schools and higher educational institutions as we know them today. There are both good and bad aspects of the Gurukula system.

The bad aspect is that children will have to learn and practice their parents’ vocation, not by choice, but as dictated by the social system. As all vocations are linked to a caste system, and the caste followed a hierarchy, social rank was determined by birth and people had no choice of selecting a desired educational or career path depending on the skills they were born with. This I think is unacceptable as it deprives people of a fundamental human right of choosing one’s educational path and vocation.

The good aspect of the Gurukula system was that it allowed to produce highly skilled practitioners as they pass through a lengthy home-based apprenticeship under the supervision of their parents, learning all aspects of the vocation. Ananda Coomaraswamy praises the system as it provided a wholesome training to the novice and contributed to sustain high quality arts and crafts and other cultural products (Medieval Sinhalese Art- introduction). That kind of education and skills development cannot be achieved by packaging them into a four-year diploma or degree program in a higher educational institution.

We have witnessed the disastrous results in the production of Ayurveda practitioners and traditional dancers by providing them with training packaged into a university degree program reduced to four-years, whereas the Gurukula system would have taken approximately 10-15 years or even longer. Although the degree-oriented training is perhaps an easy way to standardize the vocations from an administrative point of view, it has severely affected the producing of ‘wholesome’ practitioners in the traditional fields mentioned above. However, as the degree granting practice for such vocations has come a long way now and is well established within the higher education system, reverting to the Gurukula system may not be easy to accomplish.

Q: Could you comment on the modern education system practised in Sri Lanka?

A. As for providing formal education and training in other disciplines at school and university levels, I think what the British introduced was the best. We know that it served the country as the system produced disciplined and good citizens through the learning of languages, classical literature with critical thinking and emotional skills, history, civics, hygiene, mathematics, creative subjects, and environmental and other sciences.

The truth is, we do not have that British-introduced educational system in this country any longer. We maintained it until the end of the 1960s, and our schools produced good citizens and our universities produced excellent scholars. Unfortunately, may be in response to the youth uprising of 1971, or may be due to other reason, we changed both the school and the university teaching system that the British gave in the name of changing to a ‘vocation-oriented education’ hoping to produce employable school-leavers and university graduates. Both school and university curricula were truncated removing most of the subjects that contributed to the production of ‘good citizens’. For every failure, we came-up with patch-work solutions perpetuating a failing system. So, education revisions aimed at moving away from the British-introduced system and created instead a Sri Lanka-specific system which did not deliver the intended results. Therefore, I think blaming the British for our own failure to understand the fundamental aim of education and the right way of delivering such education is not fair.

Q: What do you think should be done to rectify this situation?

A. Rectifying the situation can be a Herculean task as we have marched in the wrong direction for many decades. We need to undergo a huge mindset change in the first place. We need to understand that the purpose of education is to produce good human beings capable of engaging in a righteous vocation who can serve humanity. Remember the purpose of education in ancient Greece was ‘to produce good citizens who can become future leaders of society’, and those classical ideals still hold the same currency as what it was two millennia ago.

I am a great admirer of the school curricula we had in the 1950s and the ‘60s. Our Sinhala class, through the study of both classical and folk literature trained us in critical thinking and provided us with analytical skills, socio-emotional skills, creative and innovative skills, values and morality, and skills in the use of grammatically correct Sinhala. The History of the country was taught within the framework of ‘our heritage’ using a textbook titled ‘Ape Urumaya’. The basic laws of the country and rules for good behaviour, and responsibilities of good citizens were taught in the class namely, Civics (Prajacharaya). We learnt about the environment in the class called SwabhavaAdyayanaya. The subject Mathematics taught us logical and systematic thinking to solve problems. We also had to learn crafts skills, engage in practical agriculture (called wathuweda), and about health and general hygiene. We had a fleet of well-trained teachers from the Guru-vidyalas who taught those subjects keeping all students spell-bound to the subjects they taught and produced more disciplined citizens who were capable of engaging in socially useful vocations.

However, we would not be able to achieve any of those intended goals mentioned above as long as education remains exam-oriented,with private tuition class taking over the role of the school. The private tuition system has to be eradicated immediately and school system, state or privately owned, has to be empowered as the sole deliverer of education.

Q: In your recent online ICOMOS talk mid May, you focused on some of the intangible cultural heritage categories impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, such as the Rukada Natya, Dumbara Rata Mat weaving, Bodi Puja, and Thoran making. Could you comment in detail?

A. Yes, some of the ICH elements that I mentioned are the sole livelihoods of those practitioners. Some of the professional practitioners of Rukada Natya do not have any other vocation. Sinhala and Tamil New Year festivals, Vesak and Poson celebrations are good times for them to do Rukada performances and earn some income, but the pandemic situation deprived them of that opportunity. I understand that some of the practitioners are faced with many difficulties, and I believe they deserve state support to sustain during these difficult times.

We must remember they have brought much fame to the country, being able to inscribe their art on the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2018 as Sri Lanka’s very first, and so far the only such ICH element on that prestigious list.

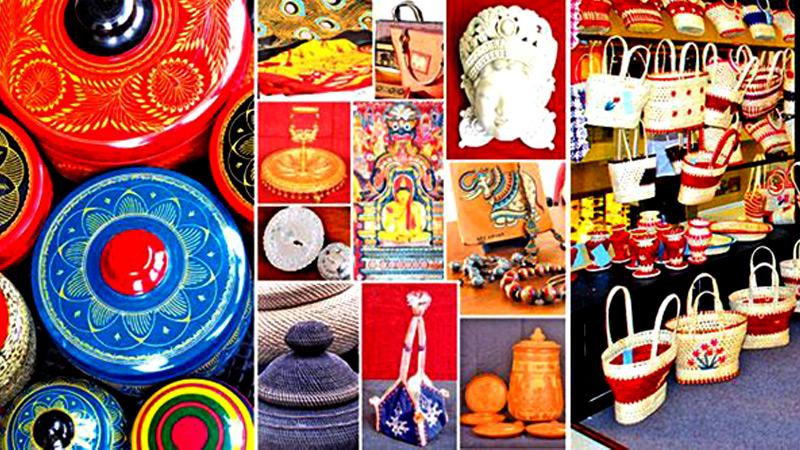

Most of the traditional crafts people including the famous Dumbara Rata mat weavers too are in trouble due to the pandemic situation. Restriction of movement has made collection and transportation of raw materials needed for the production of craft items impossible. They have also lost whatever available marketing opportunities of domestic and foreign buyers due to the prevailing situation. The country needs a well-founded mechanism to look after communities producing traditional crafts during difficult times created by pandemics or other disasters. We must not underestimate their service to the country in introducing the cultural identity and local values to the global community, and their contribution to the national economy in terms of foreign exchange earnings

Q: Today we see the near extinction of much of our intangible heritage – and just to name a few, our sokari/kolam/nadagam folk drama tradition, our general knowledge of wedakama (Athbeheth tradition passed on within the family), our respect or use of Desheeya Chikitsa (Hela Wedakama), our martial arts- Angampora, the knowledge and philosophy of cultivation using ancient cosmic knowledge based sciences of our ancestors, and many arts and crafts that were part of the Gurukula tradition. Isn’t one main reason for this is because the British changed our entire structure of existence and introduced a whole lifestyle that was totally alien to us, making us feel ashamed of some of these knowledge and practices and preventing some of our traditions by law?

A. Well, it is true the British made certain structural system changes such as governance, judiciary, education, defence services, health services, economy, trade and commerce and several others. Surely, people had to make certain lifestyle changes too in the process of adopting to those structural system changes, whether people liked it or not. However, there were many other lifestyle changes that people willingly accepted and diligently followed.

Western colonisation had taken place in many parts of the world with similar changes in the presence of varying degrees of resistance. For instance, Indians accepted many of the structural changes, but have retained much of their own lifestyles. Due to certain socio-political and cultural reasons, Sri Lankans chose to accept much of the introduced lifestyle systems, and I have no objections or regrets to it, and accept them as an essential part of social change. At the same time I respect the right of any fellow Sri Lankan to reject such socio-cultural changes or to be critical of them.

Now that the British have gone, we are free to make lifestyle choices, if we wish to do so. We have been self-ruling for over seventy years, which is almost two generations’ time. So, we need to ask why the public still practices the ‘introduced’ lifestyles, without rejecting them and going back to the traditional lifestyles such as the ones that you have mentioned.

Though I am not a specialist in the discipline of History, I would like to look at another dimension that I would call ‘people’ history’, which means the study of what the average people thought about being ruled by the British. I know that many villagers of my parents’ generation liked the British colonial rule. I still remember as a young village lad in the late 1950s and early 1960s that people of the older generation claiming “Sudda hitiyanam apita mehema venne ne”, or “Suddage kale mewaage kolam thibbe ne” or “Suddanam wedak kivvoth karanaw, aaye passé ne be kiyanne ne” and so on. The ordinary villagers often spoke appreciatively of the qualities of honesty, respect for law (neethiyataweda), and equality of the British. Such aspects of ‘people’s history’ of the colonial period has not been captured by mainstream historians who mostly looked at the official events and their records easily available at archival collections.

We know from history that the ordinary man in the late-Kandyan period lived under enormous oppression exercised by the aristocratic classes and their petty officers. Born into a strictly structured caste system, many people in the lower strata of the system enjoyed no privileges. The oppressed ordinary people loved the British rulers for ending the oppressive system, and opening avenues for social equality. The placing of Queen Victoria’s portrait at important locations in Buddhist temples in the southern coastal areas, the use of the British Coat of Arms, European decorative and pictorial elements in temple paintings, and the use of paint materials imported from Britain (eg. Aspinall’s Enamel) instead of Sinhala traditional paint materials are only a few examples to show the ordinary peoples’ acceptance and appreciation of British colonial rule.

I am not concerned about the popular thinking of dichotomies; ‘us and them’, ‘ours and theirs’ especially, when it comes to knowledge and culture. I think both are shared and inclusive entities, and should be used for the benefit of the entire humankind. We must learn to respect cultural diversity and the right of the individual to make his or her choice while accepting social change as a reality.

With the exception of the Gurukula system, I think most of the ICH elements you have mentioned are not extinct, but are forgotten or ignored due to social change. So, the ‘communities and groups’ who were or are the tradition bearers can revive or even re-generate those ICH elements if they desire to do so. However, the key word here is the revival or regeneration should be necessitated by the ‘communities and groups’ and not by extraneous agencies with vested interests.

Q: Can you speak of the extent to which heritage is taught at present in Sri Lanka as a subject at school / university level?

A. Yes, we do have a history of teaching some aspects of cultural heritage at Sri Lankan universities, not necessarily under departments with that name, but in departments of Anthropology, Archaeology, Architecture, Fine Arts, History or Sinhala. However, it was the Moratuwa University that introduced Sri Lanka’s first two-year M.Sc. program in Architectural Conservation of Monuments and Sites, and that is for the tangible heritage. Intangible heritage is taught in several universities with a more anthropological or folkloristic approach. The discipline remains open for further development in Sri Lankan universities. In the school curriculum too, some aspects of ICH are taught from Grade 8 to 11.

Q: Today, we see that the little public attention through regular discourse we get to our intangible and tangible heritage is mostly through organisations such as ICCMOS International Council on Monuments and Sites or UNESCO. Why do we not see many Sri Lankans organising discussions or workshops on their own volition?

A. We are not just represented in those organisations, but are a part of them. For instance, Sri Lanka is a member of the 24-member Intergovernmental Committee of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of the UNESCO for the four-year term from 2018-2022. In the past, Dr. Roland Silva held the Vice President position of the ICOMOS from 1987-89, and the International President position for three consecutive terms from 1990-1999 as the first non-European to hold that powerful position. So, we as a country do have the ‘power’ and ‘right’ to make decisions in those bodies if we need, provided that the government appoints the right person for the right position in the relevant local institutions such as the Department of Archaeology, the Central Cultural Fund, Department of Cultural Affairs, National Museums. If those institutions are lead by the right people, they can organise discussions or workshops locally.