Long time ago, when I visited Shekhawati in India’s Rajasthan State, I was horrified to see the elegant paintings on the walls of many havelis or the houses of rich people peeling away. They were mostly abandoned by their owners who had migrated to Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and other major cities. Some were occupied by poor homeless people.

The frescoes around them were the last thing on their minds. They simply wanted to survive. The paintings were exposed to the elements and smoke from open stoves. Besides, these were private properties. Who could decide which of these should be saved for posterity and which were to be abandoned?

When there are so many such houses in the same situation, taking a decision like this is not something that the state can easily do – if their owners also lacked interest. Years later, in a completely different context, I was confronted by the same dilemma yet again when I was reading the 1999 publication, Mortality-Immortality: The Legacy of 20th Century Art edited by Miguel Angel Corzo. In it, he noted, “for the first time in history, it is possible for us to decide what we want to save for posterity.

Selection

Do we have an obligation to the future to provide a comprehensive record of 20th century art? If we do, how do we choose what will be saved? Who makes the choices? And how do we save what we have chosen?” Indeed, this set of considerations also pertains to art and other forms of tangible culture from centuries before the 20th century when decisions must be made on what should be saved for the future.

Art is not merely a matter of aesthetics and decoration. It is also a matter of memory, history and a reference to the society’s reflections in the process of civilisation. The way the havel is in Shekhawati were losing large segments of their frescoes over time, I assumed there will be significant gaps in the future in our understandings of secular art executed in private space in the region.

It is in a similar context that Corzo has further stated, “if we accept the notion that art reflects history, then contemporary art is, in some way, a monument to contemporary civilisation. It is the cultural heritage of our time”. He was talking of 20th century art. I am thinking of art beyond the 20th century in the same sense. They too are monuments to the times gone by.

These thoughts and memories came back to me when I visited the Sri Subodharama Raja Maha Vihara in Dehiwala in January this year. Unlike the havelis in Shekhawati, Subodharamaya is a public space open to regular worship. Given its historical importance and cultural significance, a Government Gazette notification in February 2007 declared it an archaeological and protected monument, which it surely is.

Numerous frescoes

There are many stories on the history of the temple and its misfortunes in colonial times. Its histories as well as descriptions of the murals for which it is well-known, have been written about. The issue for me is not about its history and the nature of the documentation that exists, but what the present means in terms of what has survived from the past.

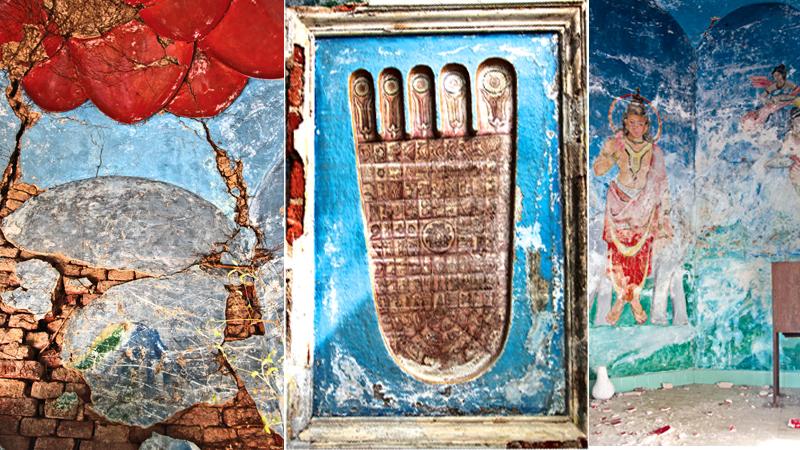

The main reason for the temple’s status as a protected monument is the existence of numerous frescoes in four different buildings. Even a superficial glance would suggest that the frescoes are from different times and are of different styles. But what survives today are from the early to the late 19th centuries though some may date from slightly earlier.

The paintings in the main shrine room and the old sermon hall are reasonably well protected – despite obvious damage – and have benefited from recent refurbishment of these buildings.

But these paintings, executed as horizontal storylines without perspective, are not merely pictorial narratives of Buddhist ethics, core religious tenets or sequences from jataka stories.

Beyond this, they also indicate how colonial experiences and imaginaries have been pictorially embedded into these paintings. There are colonial characters in uniform in Buddhist ceremonies; alcohol-drinking and gun-carrying characters depicting Buddhist notions of what is ‘bad’; demons carrying guns; gas-lit chandeliers, clocks with roman numerals and steam ships in the midst crucial story lines, and just above the main doorway into the inner chamber of the main shrine room, a decidedly ‘local-looking’ rendition of Queen Victoria.

Socio-cultural and political changes

All this presents an interesting sense of how unknown local artists had appropriated colonial and European signs, making them their own in narrating Buddhist stories. These images are not only about Buddhism, but also about socio-cultural and political changes of the time emerging as secondary narratives.

But in the other two buildings, Sath-Sathi Geya and the Sri Pada chamber, the general maintenance and the status of frescoes are in a terrible state. The buildings are dilapidated and the roofs leak. They need urgent repairs while many segments of the frescoes are badly damaged.

The Sath-Sathi Geya is effectively a gallery of frescoes and sculptures depicting the fabled seven weeks the Buddha spent immediately after his Enlightenment. The Sri Pada chamber is a relatively smaller, dome-like structure in which a sculpted footprint and statue of the Buddha are located along with paintings on the walls. The damage to these paintings and the danger they are in, is clear. Given that the temple is now a ‘protected’ monument, this obvious decline can only be arrested and restored by the state. Even if funds and expertise may be found elsewhere, the temple itself cannot undertake repairs or restorations on its own. It is simply illegal, and not sensible in the absence of a fool-proof and professional alternate system of restoration that one can bank on. But this is not a temple located in a faraway place or amidst a remote jungle. It is merely five kilometres south of Colombo 4.

How can we explain this situation? First, a decision must have been made – where such decisions can be made – that the paintings in Sath-Sathi Geya and the Sri Pada chamber are somehow ‘less’ important given that they are from the late 19th century as opposed to the better-preserved frescos in the main shrine room and sermon hall, which are possibly from the early 19th century or late 18th century.

Academic realism

The frescoes are stylistically different presenting the images with a sense of perspective and a different set of colours that indicate the influence of colonial academic realism.

They constitute an important moment in the evolution of this genre of painting in the country. This variation in style is an important consideration in the art history of the country.

Second, irrespective of the artistic and cultural merits of individual examples of frescoes, temples also have their own hierarchy when it comes to their relative cultural worth as popularly understood. For instance, it is unlikely a similar situation would befall frescoes in either the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic or Kelaniya Raja Maha Vihara.

They will be attended to quickly. In this hierarchy, Subodharamaya does not occupy the same status. In other words, in the rhetoric of cultural politics and dynamics of restoration discourses, there is no sense of equality in decision-making on what merits preservation. I find this situation truly unfortunate.

As argued by Corzo, if art reflects history and if art is a monument to the civilisation that created them, then, when the hitherto unimagined future finally arrives and most of us are no longer alive, the stories these frescoes might narrate to our decedents about our collective past would clearly be incomplete - because we have allowed some of them to disappear into oblivion.