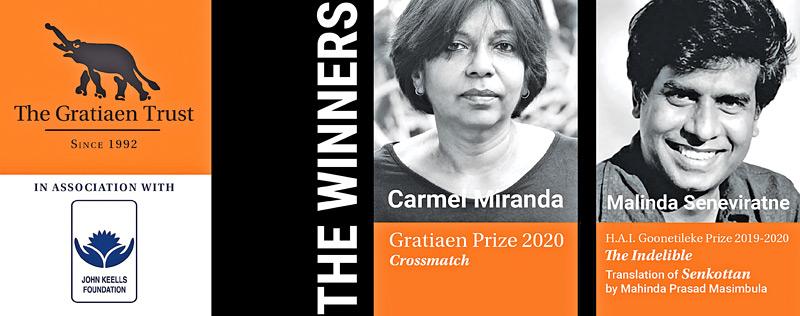

Announced over the weekend, the Gratiaen Prize for 2020 ended up being the night of Carmel Miranda and Malinda Seneviratne. Miranda’s “Crossmatch”, a thriller set in the dark corridors and nooks of Colombo’s medical world, was adjudged the best work by a residential Sri Lankan writer by a panel headed by Dr. Mahendran Thiruvarangan, the literary scholar from the University of Jaffna, of which Ashok Ferrey and Victoria Walker were members.

Since its launch a few months ago – and since being longlisted for the Gratiaen Prize in March 2021 – “Crossmatch” has courted increasing reader interest. The book has now joined an Elite bandwagon of celebrated books of which Carl Muller’s “The Jam Fruit Tree” and Lalitha Withanachchi’s “The Wind Blows over the Hills” were the original laureates and, over the past three decades, includes the work of many game-changers in Sri Lankan writing.

Since its launch a few months ago – and since being longlisted for the Gratiaen Prize in March 2021 – “Crossmatch” has courted increasing reader interest. The book has now joined an Elite bandwagon of celebrated books of which Carl Muller’s “The Jam Fruit Tree” and Lalitha Withanachchi’s “The Wind Blows over the Hills” were the original laureates and, over the past three decades, includes the work of many game-changers in Sri Lankan writing.

Malinda Seneviratne’s translation of Mahinda Prasad Masimbula’s “Senkottan” as “The Indelible”, which was awarded the HAI Goonetileke award for the best translated work, did not receive the same media attention the works shortlisted for the Gratiaen prize did, until the last leg of the extravaganza.

While the Gratiaen Prize proper evolved over four months and – like a butterfly – came through three phases that included a longlist of seven, a shortlist of five, and a finale, the “translation prize” came to public notice more as an abrupt late arrival to the party. However, having taken up the translation of “Senkottan” – a powerful novel if not for its rather hurried ending –Seneviratne has offered literary enthusiasts with a delectable promise.

Under-rated presence

Like most good literary translators around, Malinda Seneviratne has remained an under-rated presence in the literary metropolis. The reason for this under-recognition cannot solely be his not being a sworn translator. The volume of Seneviratne’s original composition and his translated work – in both their intensity and the newness – is staggering, to say the least.

At a time, I readily used excerpts of Seneviratne’s translations of Mahagama Sekara to teach the difference between sworn translators translating literary work and translation as the transfer of culture and idiom. Not soon after his days translating Sekara’s “Prabuddha”, Seneviratne won the HAI Goonetileke prize in 2012 for a translation of Simon Nawagattegama’s “Sansaranyaye Dadayakkaraya” (as “The Hunter in the Wilderness of Sansara”).

The following year, having previously been featured in four finals, he won the Gratiaen Prize with the collection “Edges”. If history, at all, teaches us a lesson, all eyes should be on next year’s Gratiaen Prize and how Malinda Seneviratne features in it. If at all, it will be a shame if Seneviratne is invited next year to judge the prize.

The Gratiaen Prize is now almost 30 years old. As the prize has grown in stature, reach and its dominance over the prize tables in Sri Lankan creative writing, it has also firmly held on to the motto “One Shot”. This single shot has been rigorously implemented as a comprehensive in-house policy in the selection of judging panels. In 29 years, any given appointed judge (1993-2021) has not presided over the prize to exceed a covetous single occasion.

The contribution of the prize to Sri Lanka’s creative world in mind, I feel that it is high time that this policy is revised. To clarify further, I find it an irreparable loss that some brilliant minds and leaders of Sri Lanka’s English literary world– men and women who have already judged the prize in the 1990s and 2000s as first choice selections – are not made use of in an age where the prize is more established, recognised, and – in certain years – have had as adjudicators foreigners whose literary brilliance doesn’t exactly match up to whom we have lost to the “One Shot” rule.

Intriguing outcome

As the Gratiaen Prize evolves into its fourth decade, an intriguing outcome to look forward is as to who would succeed in scoring a second Gratiaen plum. This year’s final featured Lal Medawattegedara (shortlisted for “Restless Rust”) who, in 2012, had won the prize for his bestseller “Playing Pillow Politics in MGK”. Recent finals have featured Shehan Karunatilaka (the winner of 2008, among the finalists of 2015, 2016 and 2018) and Vivimarie Vander Poorten (winner of 2007 in 2016). Along with the writer of this article, Neil Fernandopulle and Sumathy Sivamohan are the others in this category of returnees demanding a second shot.

Shehan Karunatilaka (arguably the most prolific writer of the past decade) making three finals in four years between 2015 and 2018 and yet falling short of the historical target serves as a measurement as to how uphill a task a second Gratiaen win appears.

This should only make writers rise to the challenge. Among other things, JM Coetzee is not a bad role model to have. In fact, Malinda Seneviratne’s triumph with “The Indelible” is probably the first instance where the same writer (in Seneviratne’s case, in 2012 and 2021) has scored twice in one of the two categories the Gratiaen Prize offers.

Having met her at the New Ink Literary Forum in June, I had the opportunity to interact with Carmel Miranda. With the unaffected air of a Shakespearean character with whom she shares a name, she shared opinion on the writing game: frank opinions about literature in Colombo in an air which, in its not buying into false idols, serves writers good. Miranda read and spoke at a New Ink panel she shared with Yasmin Azad and Neshantha Harischandra and commented on the dearth of good detective fiction and mystery thrillers in Sri Lanka and how “Cross-match” was born out of her desire to address this vacuum.

As Sri Lankan English writing becomes increasingly globalised by the day, the role the Gratiaen Trust as an institute and writers who contribute to its platforms (such as the Gratiaen Prize) will be assigned by the coming decade will have a far-reaching impact on how resident Sri Lankan writing is measured, valued, and set in circulation.

As I have commented elsewhere, globalisation through the 1990s and 2000s has transferred the visibility of being a Sri Lankan writer as the work-right of our expatriate cousins. My energies are invested in reversing this process. The Malindas and the Mirandas as well as those who were shortlisted or were exempted from lists – as well as lit-friendly organisations including the Gratiaen Trust – have a common stake in this overarching programme.

The writer of this article, Vihanga Perera is a writer of fiction and poetry, a researcher in literature and formerly an academic at a public university in Sri Lanka.