You know Frida Kahlo – of course, you do. She is the most famous female artist of all time and her image is instantly recognisable and unavoidable. Kahlo can be found everywhere, on T-shirts and notebooks and mugs. While writing this piece, I spotted a selection of cutesy cartoon Kahlo merchandise in the window of a shop, maybe three minutes' walk from my home. I bet many readers are similarly in striking distance of some representation of her, with her monobrow and traditional Mexican clothing, her flowery headbands and red lipstick.

Partly, this is because her own image was a major subject for Kahlo – around a third of her works were self-portraits. Although she died in 1954, her work still reads as bracingly fresh: her self-portraits speak volumes about identity, of the need to craft your own image and tell your own story. She paints herself looking out at the viewer: direct, fierce, challenging.

Partly, this is because her own image was a major subject for Kahlo – around a third of her works were self-portraits. Although she died in 1954, her work still reads as bracingly fresh: her self-portraits speak volumes about identity, of the need to craft your own image and tell your own story. She paints herself looking out at the viewer: direct, fierce, challenging.

All of which means Kahlo can fit snugly into certain contemporary, feminist narratives – the strong independent woman, using herself as her subject and unflinchingly exploring the complicated, messy, painful aspects of being female. Her paintings intensely represent dramatic elements of a dramatic life: a miscarriage, and being unable to have children; bodily pain (she was in a horrific crash at 18, and suffered physically all her life); great love (she had a tempestuous relationship with the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, as well as many other lovers, male and female, including Leon Trotsky), and great jealousy (Rivera cheated on her repeatedly, including with her own sister).

But that’s not all they show – her art is not always just about her life, although you could be forgiven for assuming it was. Books are written about her trauma, her love life; she's been the subject of a Hollywood movie starring Salma Hayek. Kahlo has become a bankable blockbuster topic, guaranteed to get visitors through the door of galleries, even if what they see is often more about the woman than her art.

Her work

But what about her work? For some art historians, the relentless focus on the person rather than the output has become tiresome, which is why a new, monumental book – Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings – has just been published by Taschen, offering for the first time a survey of her entire oeuvre. Mexican art historian Luis-Martín Lozano, working with Andrea Kettenmann and Marina Vázquez Ramos, provides notes on every single Kahlo work we have images of – 152, including many lost works we only know from photographs.

But what about her work? For some art historians, the relentless focus on the person rather than the output has become tiresome, which is why a new, monumental book – Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings – has just been published by Taschen, offering for the first time a survey of her entire oeuvre. Mexican art historian Luis-Martín Lozano, working with Andrea Kettenmann and Marina Vázquez Ramos, provides notes on every single Kahlo work we have images of – 152, including many lost works we only know from photographs.

Speaking to Lozano on a video call from Mexico City, I ask if a comprehensive survey of her work is overdue, despite there being so many shows about her all over the world.

"As an art historian, my main interest in Kahlo has been in her work as an artist. If this had been the main concern of most projects in recent decades, maybe I would say this book has no reason to be. But the truth is, it hasn't," he said. "Most people at exhibitions, they're interested in her personality – who she is, how she dressed, who does she go to bed with, her lovers, her story."

Because of this, exhibitions and their catalogues have often focused on that story and tend to "repeat the same paintings and the same ideas about the same paintings. They leave aside a whole bunch of works," said Lozano. Books also re-tread the same ground: "You repeat the same things. It will sell – because everything about Kahlo sells. It's unfortunate to say, but she's become a merchandise. But this explains why [exhibitions and books] don't go beyond this – because they don't need to."

The result is that certain mistakes get made – paintings mis-titled, mis-dated, or the same poor-quality, off-colour photographs reproduced. But it also means that ideas about what her works mean get repeated ad infinitum. "The interpretation level becomes contaminated," suggested Lozano. "All they say about the paintings, over and over, is 'oh it's because she loved Rivera', 'because she couldn't have a child', 'because she's in the hospital'. In some cases, it is true – but there's so much more to it than that."

The number of paintings – 152 – is not an enormous body of work for a major artist. And yet, astonishingly, some of these have never been written about before: "never, not a single sentence!" laughed Lozano. "It's kind of a mess, in terms of art history."

Offering a comprehensive survey of her work means bringing together lost or little-known works, including those that have come to light in auctions in the past decade or so and others that are rarely loaned by private collectors and so have remained obscure. Lozano hopes to open up our understanding of Kahlo. "First of all – who was she as an artist? What did she think of her own work? What did she want to achieve as an artist? And what do these paintings mean by themselves?"

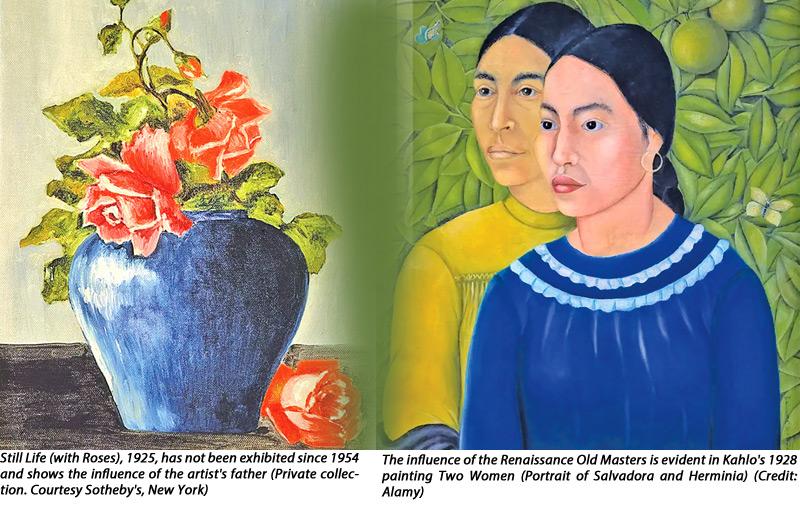

This means looking again at early works, which might not be the sort of thing we associate with Kahlo – but reveal how much she was inspired by her father, Guillermo, a professional photographer and an amateur painter of floral still lives. Pieces such as the little-known Still Life (with Roses) from 1925, which has not been exhibited since 1953, are notably similar in style to his.

Kahlo continued to paint astonishing, vibrant still lives her whole career – although they are less well-known to the general public than her self-portraits, less collectable and less studied. An understanding of their importance to her has been strengthened since Lozano and co discovered documents revealing Kahlo's life-long interest in the symbolic meaning of plants. She learnt this from her father and discussed it in letters with her half-sister Margarita (her father's child from an earlier marriage), who became a nun.

The missing links

Kahlo and Margarita's letters "talk about the symbolic meaning of flowers and fruits and the garden of Eden, that our body is like a flower we have to take care of because it was ripped off from paradise," said Lozano. "This is amazing and proves why this topic of still lives and flowers had such meaning to her."

He offers a new interpretation of a painting from 1938, called Tunas, which depicts three prickly pears in different stages of ripening – from green and unripe to a vibrant, juicy, blood-red – as representing Kahlo's own understanding of her maturation as an artist and person, but as also potentially having religious symbolism (the bloody flesh evoking sacrifice).

The Complete Paintings book also takes pains to reveal the depths of Kahlo's intellectual engagement with art-world developments – countering the notion that she was merely influenced by meeting Rivera in 1928, or that her work is some self-taught, instinctive howl of womanly pain. Her paintings reveal Kahlo's research into and experiments in art movements, from the youthful Mexican take on Modernism, Stridentism, to Cubism and later Surrealism.

"Frida Kahlo's paintings were not only the result of her personal issues, but she looked around at who was painting, what were the trends, the discussions," said Lozano. He points to her first attempts at avant-garde paintings – 1927's Pancho Villa and Adelita, and the lost work If Adelita, both of which use sharp, Modernist lines and angles – as proof that "she was looking at trends in Mexican art even before she met Rivera".

You can also see her interest in Renaissance Old Masters, which she discovered prints of in her father's library, in early work: it's suggested her 1928 painting, Two Women (Portrait of Salvadora and Herminia), depicting two maids against a lush, leafy background, was inspired by Renaissance portraiture traditions, as seen in the works of Leonardo da Vinci. Bought in the year it was painted, the location of this work remained unknown until it was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2015.

Lost work

Given she only made around 152 paintings, a surprising number are lost. But then, Kahlo wasn't so successful in her lifetime – she didn't have so many shows, or sell that many works through galleries and dealers. Instead, many of her paintings were sold or given away directly to artists, friends and families, as well as movie stars and other glittering admirers, often living abroad. That means less of a paper trail, making it harder to track down works.

In honesty, looking at black-and-white pictures of lost portraits probably isn't going to prove revelatory to anyone beyond the most hard-core scholars – although there are some astonishing paintings still missing. One lost 1938 image, Girl with Death Mask II, depicts a little girl in a skull mask in an empty landscape; it chills, and we know Kahlo discussed this painting in relation to her sorrow at being unable to conceive. Check your attics, too, for Kahlo's painting of a horrific plane crash – which we only have a photograph of now – which she's known to have made in a period of great personal turmoil in the years after discovering her sister's affair with Rivera in 1935.

Like another of her very well-known paintings, Passionately in Love or A Few Small Nips, depicting a woman murdered by her husband, The Airplane Crash was based very closely on a real-life news report; Lozano's team have unearthed both original articles in their research. While Kahlo may have been drawn to these traumatic events because she was suffering pain in her own life, her degree of almost documentary precision in external news stories here should not be overlooked.

Kahlo was an avowed Communist and politically engaged all her life, but it is in less well-known works from the final years of her life where you see this most explicitly emerge. At this time, she suffered a great deal of pain and underwent many operations, eventually including amputation below the knee. But Kahlo continued painting till 1953, with difficulty but also with renewed purpose. Her biographer Raquel Tibol documented her saying: "I am very concerned about my painting.

More than anything, to change it, to make it into something useful, because up until now all I have painted is faithful portraits of my own self, but that's so far removed from what my painting could be doing to serve the [Communist] Party. I must fight with all my strength so that the small amount of good I am able to do with my health in the way it is will be directed toward helping the Revolution. That's the only real reason for living."

This resulted in works such as 1952's Congress of the Peoples for Peace (which has not been exhibited since 1953), showing a dove in broad fruit tree – and two mushroom clouds, representing Kahlo's nightmares about nuclear warfare. She became an active member of many peace groups – collecting signatures from Mexican artists in support of a World Peace Council, helping form the Mexican Committee of Partisans for Peace, and making this painting for Rivera to take to the Congress of the Peoples for Peace in Vienna in 1952.

Doves feature in several of her late still lives – as do an increasing number of Mexican flags or colour schemes (using watermelons to reflect the green, white and red of the flag), suggesting Kahlo's intention was that her work should show her nationalism and Communism. More uncomfortably, her final paintings include loving depictions of Stalin, as her politics became more militant.

Perhaps her most moving late painting, however, is a self-portrait: Frida in Flames (Self-portrait Inside a Sunflower). It's harrowing, painted in thick, colourful impasto; shortly before her death, Kahlo slashed at it with a knife, scraping away the paint, frustrated at her inability to make work or perhaps in an acknowledgment that her end was nearing. Tibol, who was witness to this decisive, destructive act, called it "a ritual of self-sacrifice". "It's a tremendous image," said Lozano.

"It's very interesting in terms of aesthetics – when your body is not working anymore, when your brain is not enough to portray what you want to paint, the only source she's left with is to deconstruct the image. This is a very contemporary, conceptual position about art: that the painting exists not only in its craft, but also what I think the painting stands for."

We are left with a painting that is imperfect, certainly a world away from the fine, smooth surfaces and attention to detail of Kahlo's more famous self-portraits – but it, nonetheless, is an astonishingly powerful work that deserves to be known. There is something tremendously poignant in an artist so well-known for crafting their own image using their final creative act to deliberately destroy that image. Even in obliterating herself, Kahlo made her work speak loudly to us.

Courtesy: BBC.com