Author – Chinua Achebe

Publisher – Anchor Books:

A Division of Random House, Inc.

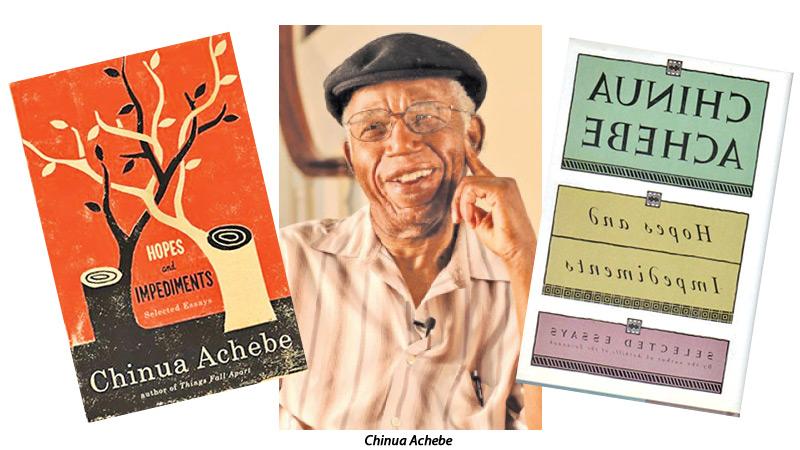

Author, Coauthor and Editor Chinua Achebe who died a decade ago, is considered the father of modern African literature. Apart from his fictions, he is the author of many non-fictions. ‘Hopes and Impediments’ is a collection of essays by him through which he discusses the place of literature and art in society.

The collection contains his writings and lectures over the course of his career, from his groundbreaking and provocative essay on Joseph Conrad and ‘Heart of Darkness’ to his assessments of the novelist’s role as a teacher and of the truths of fiction. As the back-cover of the book suggests, “Achebe reveals the impediments that still stand in the way of open, equal dialogue between Africans and Europeans, between blacks and whites, but also instills us with hope that they will soon be overcome.”

‘Heart of Darkness’

The book consists of 14 chapters, and the first chapter is his most provocative essay titled ‘An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness’. In the essay, he throws light to Conrad’s attempt in delineating Africa. Achebe accuses Conrad for bringing up prejudices against the Africans through his novella:

“Heart of Darkness’ projects the image of Africa as ‘the other world’, the antithesis of Europe and therefore, of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality. The book opens on the River Thames, tranquil, resting peacefully ‘at the decline of day after ages of good service done to the race that peopled its banks.’ But the actual story takes place on the River Congo, the very antithesis of Thames. The River Congo is quite decidedly not a River Emeritus. It has rendered no service and enjoys no old-age pension. We are told ‘going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginning of the world.’” (Pages 3-4)

Achebe elaborates white racism against Africans in the novel. He observes that “Joseph Conrad was a thoroughgoing racist.” (Page 11)

He highlights the importance of glorifying humanity in a novel analysing Conrad’s book which considers as a great art of work:

“The real question is the dehumanisation of Africa and Africans which this age-long attitude has fostered and continues to foster in the world. And the question is whether a novel which celebrates this dehumanisation, which depersonalises a portion of the human race, can be called a great work of art. My answer is: No, it cannot. I do not doubt Conrad’s great talents. Even ‘Heart of Darkness’ has its memorably good passages and moments:

“The reaches opened before us and closed behind, as if the forest had stepped leisurely across the water to bar the way for our return.”

“Its exploration of the minds of the European characters is often penetrating and full of insight. But all that has been more than fully discussed in the last fifty years. His obvious racism has, however, not been addressed. And it is high time it was!” (Pages 12-13)

Impediments to dialogue

In the second chapter, ‘Impediments to Dialogue Between North and South’, Achebe starts a discussion on the importance of maintaining good relations between the continents. He says, “The relationship between Europe and Africa is very old and also very special.

The coasts of North Africa and Southern Europe interacted intimately to produce the beginnings of modern European civilization. Later, and much less happily, Europe engaged Africa in the tragic misalliance of the slave trade and colonialism to lay the foundations of modern European and American industrialism and wealth.” (Page 22)

The coasts of North Africa and Southern Europe interacted intimately to produce the beginnings of modern European civilization. Later, and much less happily, Europe engaged Africa in the tragic misalliance of the slave trade and colonialism to lay the foundations of modern European and American industrialism and wealth.” (Page 22)

Achebe reveals some of the major impediments to the dialogue between the whites and the blacks: “Because of the myths created by the white man to dehumanise the Negro in the course of the last four hundred years – myths which have yielded perhaps psychological, certainly economic, comfort to Europe – the white man has been talking and talking and never listening because he imagines he has been talking to a dumb beast.” (Pages 23-24)

However, Achebe hopes one day, the dialogue would be started: “The hope is that if the white man is so curious about the black man, one day he may actually stop and listen to him. The fear is that the white man has found and used so many evasions in the past to replace or stimulate dialogue to his own satisfaction that he may go on doing it indefinitely.” (Page 25)

Criticising Naipaul

In the same chapter, Achebe criticises Nobel Prize winning author V.S. Naipaul as well. He says that Naipaul has done injustice to Africa, India and South America by segregating them in his novel ‘A Bend in the River’. Once the New York Times Book Review carried a laudatory review of Naipaul’s novel ‘A Bend in the River’ and also a long interview with him. The interview was conducted by the distinguished American writer and critic, Elizabeth Hardwick. Achebe criticises the interview:

“Hardwick’s last question to Naipaul was: ‘What is the future in Africa?’ His reply, smart and predictable: ‘Africa has no future.’ This modern Conrad, who is partly native himself, does not beat about the bush!” (Page 28)

Achebe ends the chapter as follows:

“We are the white man’s rubbish,’ says an Athol Fugard character, ‘His rubbish is people.’ When that changes, dialogue may have a chance to begin. If the heap of rubbish doesn’t catch fire meanwhile and set the world ablaze.” (Pages 28-29)

Literary world

The third chapter, ‘Named for Victoria, Queen of England’, is a short biographical note of Achebe where he recounts his father, mother, religion and his reading habit.

In the fourth chapter, ‘The Novelist as Teacher’, he discusses the role of a novelist. Achebe believes that art has social and moral dimension. This is how he describes his writing with regard to the media of education:

“I would be quite satisfied if my novels (especially, the ones I set in the past) did no more than teach my readers that their past – with all its imperfections – was not one long night of slavery from which the first Europeans acting on God’s behalf delivered them. Perhaps what I write is applied art as distinct from pure. But who cares? Art is important, but so is education of the kind I have in mind. And I don’t see that the two need be mutually exclusive.” (Page 45)

In the next chapter, ‘The Writer and His Community’, Achebe talks of the artistic forms and literary outputs of the Africans. He shares his own thoughts on writing: “Part of my artistic and intellectual inheritance is derived from a cultural tradition in which it was possible for artistes to create objects of art which were solid enough and yet make no attempt to claim, and sometimes even go to great lengths to deny, personal ownership of what they have created. I am referring to the tradition of ‘mbari’ art in some parts of Igboland.” (Page 48)

The sixth chapter of the book, ‘The Igbo World and Its Art’, deals with Achebe’s homeland, Nigeria’s traditional art, especially its dance and masquerade. According to him, of all the art forms, dance and masquerade would appear to have satisfied the Igbo artistic appetite: “If the masquerade were not limited to the male sex alone, one might indeed call it the art form par excellence for it subsumes not only the dance but all other forms.” (Page 65)

Through the next eight chapters entitling ‘Colonial Criticism’, ‘Thoughts on the African Novel’, ‘Work and Play in Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard’, ‘Don’t Let Him Die: A Tribute to Christopher Okigbo’, ‘Kofi Awoonor as a Novelist’, ‘Language and the Destiny of Man’, ‘The Truth of Fiction’, ‘What has literature Got to Do with It’, readers can know Achebe’s literary thoughts and assessments and book reviews.

In the end, ‘Hopes and Impediments’ gives readers important insights into the novel, the African literature and European thinking of art which are brilliant and provocative.