Alfred ‘Al’ Adolph Oerter Jr. was an Olympic legend. He was the first track and field athlete to win four successive Olympic titles. He secured gold medals in discus throw in 1956, 1960, 1964 and 1968 Summer Olympic Games, setting new Olympic records on each occasion, although he was never the favourite to win the event.

His third victory in 1964 was remarkable for the fact that he overcame the handicap of neck and rib injuries, but still managed to set a career best. He also set four world records, the first of which in 1962 gave him the distinction of being the first man to record a legal throw of over 200 feet (60.96 metres).

Birth and Growth

Al Oerter was born on August 19, 1936, in Astoria, Queens, New York City to parents of German and Czech extraction. Growing up in New Hyde Park, Oerter showed that he was a special athlete by throwing the lighter discus used in high school 184 feet, 2 inches, a national prep record at the time. He attended Sewanhaka High School in Floral Park and began his athletic career at the age of 15 when a discus landed at his feet and he threw it back past the crowd of throwers.

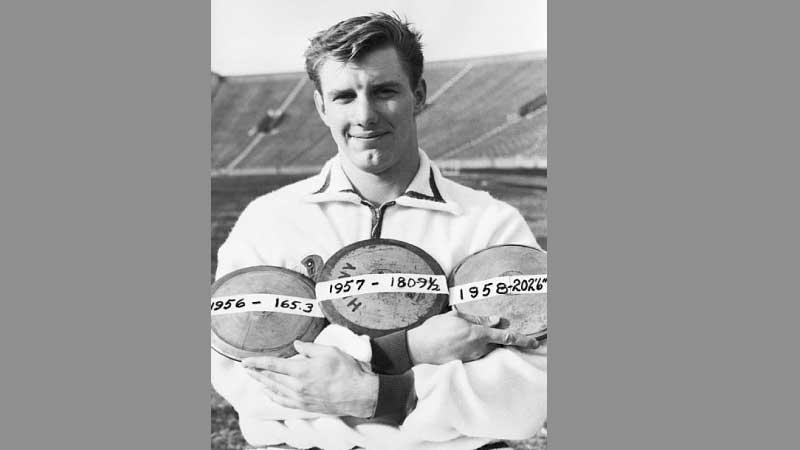

Oerter continued throwing and eventually earned a scholarship to the University of Kansas in 1954 where he became a member of Delta Tau Delta fraternity. A large man of almost 6’ 4” (193 cm) and 280 pounds (127 kg), Oerter was a natural thrower. Competing for Kansas, he became the NCAA discus champion in 1957 and 1958.

Melbourne 1956

Al Oerter began his Olympic career at the Melbourne 1956 Summer Olympics. He was not considered the favorite but he felt a rush during the competition and unleashed a throw of 184 feet 22 inches (56.64 m), which at the time was a career best. The throw was good enough to win the competition by more than 5 inches (130 mm). In 1957, it seemed that Oerter’s career would be over at the age of 20 when he was nearly killed in an automobile accident.

Rome 1960

He recovered in time to compete at the Rome 1960 Summer Olympics, where he was the slight favorite over teammate Rink Babka, who was the world record holder. Babka was in the lead for the first four of the six rounds. He gave Oerter advice before his fifth throw; Oerter threw his discus 194 feet 2 inches (59.18 m), setting an Olympic record.

Babka settled for the silver medal when he was not able to beat Oerter’s throw. During the early 1960s, Oerter continued to have success and set his first world record in 1962. In the process, he was the first to break 200 feet in the discus.

Tokyo 1964

He was considered a heavy favorite to win a third gold medal at Tokyo in 1964. Oerter was hampered by injuries before the Games began. He was bothered by a neck injury that required him to wear a neck brace, and a week before the start of the competition he tore cartilage in his ribs.

Oerter was competing in great pain, but he set a new Olympic standard and won a third Olympic gold medal despite not being able to take his last throw due to the pain from his ribs. He’d told the doctors, “These are the Olympics. You die for them.”

Mexico City 1968

Oerter returned to the Olympics in 1968 at Mexico City, however teammate Jay Silvester was cast as the favorite. Many felt Oerter, who was then 32, could not win the event because he had never thrown as far as Silvester did on his average throws.

At the Olympics, however, Oerter hurled another Olympic record throw of 64.78 metres (212.5 ft) on his third throw. His record held and he became the first track and field athlete to win gold medals in four consecutive Olympic Games. This accomplishment would be equaled many years later by fellow Americans Carl Lewis and swimmer Michael Phelps.

Although his original goal was to win five gold medals, Oerter retired from Olympic competition after the 1968 Games with four because of the sacrifices and pressures of being an Olympic champion.

Al Oerter believed that he and his sport, the discus throw, were one with the past and the future. He was awed by the antiquity of it all. He had studied how the technique had been handed down over thousands of years, from one athlete to another.

Al Oerter believed that he and his sport, the discus throw, were one with the past and the future. He was awed by the antiquity of it all. He had studied how the technique had been handed down over thousands of years, from one athlete to another.

After the medal ceremony at the Mexico City 1968, an exhausted Al Oerter was being interviewed by ABC sportscaster Howard Cosell, who pointed out Al’s two daughters in the crowd, ages 6 and 8 years old. Al waved to them and, in that instant, realized there would be no such thing as going for a fifth Olympic Games. It was time for him to focus on being with his family; to devote his time to raising his girls and not miss one day of their growth.

Retirement

In 1969, Al had been invited to a few track and field relays on the west coast. As a 4-time gold medal winner, he was told that he would be presented with plaque, cup or other memorabilia to celebrate his Olympic achievements. Even though he was in retirement, hadn’t trained in months, or even lifted weights to increase capability, he could still throw past 190 feet.

He accepted an invitation to go out to one meet in Los Angeles. At the competition, Al was throwing over 190 feet, which he thought was pretty good for not having really trained for it. Just before his sixth turn in the circle, he decided that “This is going to have to be the final throw of my life.” Retirement was real. His last throw was like the others, and put him in fifth or sixth place.

Al wrote, “After the competition was over, I went up to one of my fellow competitors and presented my discus to him. I think he thought I was crazy and received it with a quizzical look on his face.” It was a wooden Gill model, popular among throwers in the late 1960’s.

Al was not trying to give away a free discus. Rather, it was his own symbolic gesture, with special meaning to himself, of giving up the event and passing on the torch to the next generation of discus throwers. He was maintaining the discus continuum going back to the ancient Greeks.

Al said: “So, I gave him the discus and left. He thanked me, but looked at me and looked at the discus with a question of, ‘What is this guy doing?’”Al returned to his family, his Long Island home, and appeared in a couple of meets after that, when, as he said: “It was for a good cause. Anything to help out.”

The last Throw

While he narrowly failed to qualify for the U.S. Olympic team in 1980, which ultimately did not compete (there being a U.S. boycott), he made the longest throw of his career and the world’s longest that year, 69.46 metres (227 feet 11 inches).

“In 1997, that discus (from 1969) came back,” Al wrote. “I was at the United States Olympic Committee Training Center in Colorado Springs and one of the folks who works at the center asked me if I would sign a discus. I said, ‘Sure!’

“So, she brings out this discus, which was an old, worn, wooden Gill model. I recognized it as possibly the one I had thrown all of those years before. Someone had lacquered it to preserve it. It had the same markings that I remembered being put on it by the various officials who had weighed and measured it to make sure it was legal to throw in competition.

“Sure enough, it was the same discus. And now, after all of those years, it was in my hands again. It was a very nostalgic thing and I signed it and dated it with all the Olympic years. It was a bit of my past corning back, represented by the discus I had passed on to someone else. It was a unique moment.”

I now had many questions that needed answers. Where was this “Last Throw” discus, now? Who was the original recipient and how did it make its way to the USOC Training Center?

It was time to put on my Sherlock Holmes hat and quote Arthur Conan Doyle, “The game is afoot.”

Comeback effort

He later eyed a comeback and took anabolic steroids in 1976 under medical supervision in order to put on muscle mass. However, he stopped the course as this affected his blood pressure and failed to give much improvement on the field. After this he advised athletes to avoid such drugs and focus on training and technique instead. He was critical of the increase of drug use and the subsequent testing in track and field, stating that it had destroyed the culture of athlete camaraderie.

Oerter did make an attempt to qualify for the American team in 1980 but finished fourth. He nonetheless set his overall personal record of 69.46 metres (227.9 ft) that year at the age of 43. Dr. Gideon Ariel, a former Olympic shot putter himself for Israel, had developed a business of biomechanical services, and Oerter after working with Ariel at the age of 43, threw a discus 27 feet farther than his best gold medal performance.

Oerter did make an attempt to qualify for the American team in 1980 but finished fourth. He nonetheless set his overall personal record of 69.46 metres (227.9 ft) that year at the age of 43. Dr. Gideon Ariel, a former Olympic shot putter himself for Israel, had developed a business of biomechanical services, and Oerter after working with Ariel at the age of 43, threw a discus 27 feet farther than his best gold medal performance.

Though active at a world-class level into his 40s, he fell short again in bids for the U.S. Olympic team in 1984 and 1988. He was a world record holder in Masters track-and-field competition in the 1980s.

When filming for a TV segment, he unofficially threw about 245 feet (75 m), which would have set a still-standing world record. In later years, Oerter carried the Olympic flag for the 1984 Summer Olympics, then carried Olympic flame into the stadium for the 1996 Olympic Games.

Art of the Olympians

As a child, Oerter had frequently traveled to his grandparents’ home in Manhattan and admired their art collection. As a retired athlete, Oerter became an abstract painter. Oerter enjoyed the freedom of abstract art, and thus decided against formal schooling for his art, as he thought it might stifle his creativity.

Part of Oerter’s work was his “Impact” series of paintings. For these works, Oerter would lay a puddle of a paint on a tarp, and fling a discus into it to create splashing lines on a canvas positioned in front of the tarp. If the discus landed painted-face up, Oerter would sign it and give it to whoever purchased the painting.

In 2006, he founded the Art of the Olympians organization and held an Olympian Art exhibition in his home town of Fort Myers. This first show included artworks and sculptures from 14 Olympians, including Florence Griffith Joyner, Ronald Bradstock, Shane Gould, Cameron Myler, Rink Babka and Larry Young.

Later that year the exhibit traveled to New York City for shows at the United Nations, the New York Athletic Club and then at the National Arts Club. Art of the Olympians also had their work on display on the giant Panasonic Astro-Vision screen in Times Square for the entire month November 2006.

Oerter and other Olympian artists were also featured on the CBS Morning Show to discuss their New York Tour. In mid-2007, Art of the Olympians was given the rights to use the word Olympian by the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), an act protected by Congress.

Art of the Olympians continued to grow 10 years after their first exhibition. The organization now has 50 Olympian and Paralympian artists on its roster including two posthumous members: Al Oerter and Florence Griffith-Joyner. Over the past decade Art of the Olympians artists and their artwork have been seen on numerous TV networks including CBS, NBC, BBC, CNN, PBS, the USA Network and UK’s Channel Four and had Exhibitions at three Olympic and Paralympic Games: Beijing 2008, Vancouver 2010 and London 2012. And for three and half years, between 2010 and 2013, Art of the Olympians had dozens of group and solo exhibitions at their museum and gallery in Fort Myers, Florida.

Later life and death

Oerter had struggled with high blood pressure his entire life, and in the 2000s, he became terminally ill with cardiovascular disease. On March 13, 2003, Oerter was briefly clinically dead; a change of blood pressure medications caused a fluid build-up around his heart.

As Oerter’s heart condition progressed, he was advised by cardiologists he would require a heart transplant. Oerter dismissed the suggestion. “I’ve had an interesting life,” he said, “and I’m going out with what I have.” Oerter died on October 1, 2007 of heart failure in Fort Myers, Florida at the age of 71. He was survived by his wife and two daughters.

Upon learning of Oerter’s death, track and field historian and blogger Mike Young wrote that Oerter was arguably the greatest Olympian of all time. On March 7, 2009, the Al Oerter Recreation Center, operated by New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, opened in Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Flushing, Queens.

Legend

Oerter was in the first class to be inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in 1983. Oerter was inducted into the Suffolk Sports Hall of Fame on Long Island in the Track & Field Category with the Class of 1990. In 2005, Oerter was inducted into the Nassau County Sports Hall of Fame.

His wife Cathy Oerter said: “He was a gentle giant. He was bigger than life.” IAAF President Lamine Diack commented: “With the sad passing of Al Oerter, the sport of Athletics has lost one of its foremost heroes. He was a colossus of a man who towered over this event setting an impeccable example to the youth of his era and today. The global Athletics family mourns his loss.”

(The author is the winner of Presidential Awards for Sports and recipient of multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. He can be reached at [email protected])