Every literary work is different from another. It means every writer follows his or her own set of rules or techniques when writing fiction. This art of fiction by writers is very important for budding writers, and also for readers who are curious about how the story is formed. Therefore, we are going to present you some literary techniques followed by some great writers.

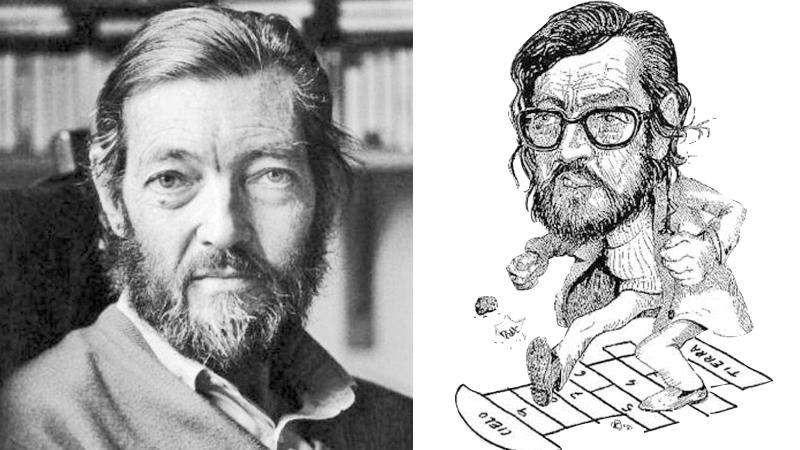

Thus, the first techniques that we are going to know about are art of fiction by Argentinean writer Julio Cortázar. Cortázar is one of two great short story writers in Argentina - other is Jorge Luis Borges. He was born in Brussels on August 26, 1914, and grown up in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Before venturing into writing, he was a teacher worked at a school in Buenos Aires. Though started from short stories, Cortázar engaged in writing novels as well. ‘The Winners’ (1960), ‘Hopscotch’ (1963), ‘62: A Model Kit’ (1968) and ‘A Manual for Manuel’ (1973) are some of them.

Before venturing into writing, he was a teacher worked at a school in Buenos Aires. Though started from short stories, Cortázar engaged in writing novels as well. ‘The Winners’ (1960), ‘Hopscotch’ (1963), ‘62: A Model Kit’ (1968) and ‘A Manual for Manuel’ (1973) are some of them.

The first short story collection of his is ‘Bestiario’ (1951), second is ‘Final del juego’ (End of the Game) (1956). The third is ‘Las armas secretas’ (1959) while the forth is ‘Historias de cronopios y de famas’ (Cronopios and Famas) (1962).

He published more than ten short story collections including ‘Todos los fuegos el fuego’ (All Fires the Fire) (1966), ‘Blow-up and Other Stories (1968)’, Queremos tanto a Glenda (We Love Glenda So Much) (1980) and Deshoras (Unreasonable Hours) (1982).

His stories are generally regarded as fantastic, and most of them, he wrote while living in Paris, because since 1951 he had been living in Paris. After suffering from cancer, he died on February 12, 1984, at the age of 69. Just before his death he was interviewed by Jason Weiss for ‘Paris Review’ literary magazine where he reveals most of his art of fiction. Hence, we quote that Paris Review interview to show his literary techniques.

Not a serious writer

“I don’t like the idea of ‘serious,’ because I don’t think I am serious, at least not in the sense where one speaks of a serious man or a serious woman. But in these past few years, my efforts concerning certain Latin American regimes — Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and now above all Nicaragua — have absorbed me to such a point that I have used the fantastic in certain stories to deal with this subject — in a way that’s very close to reality, in my opinion. So, (when writing) I feel less free than before.

That is, thirty years ago I was writing things that came into my head and I judged them only by aesthetic criteria. Now, though I continue to judge them by aesthetic criteria, first of all because I’m a writer — I’m now a writer who’s tormented, very preoccupied by the situation in Latin America; consequently that often slips into my writing, in a conscious or in an unconscious way. But despite the stories with very precise references to ideological and political questions, my stories, in essence, haven’t changed. They’re still stories of the fantastic.”

What I do must be literature

“The problem for an engagé writer, as they call them now, is to continue being a writer. If what he writes becomes simply literature with a political content, it can be very mediocre. That’s what has happened to a number of writers. So, the problem is one of balance. For me, what I do must always be literature, the highest I can do . . . to go beyond the possible. But, at the same time, to try to put in a mix of contemporary reality. And that’s a very difficult balance.”

Form of play

“For me, literature is a form of play. But I’ve always added that there are two forms of play: football, for example, which is basically a game, and then games that are very profound and serious. When children play, though they’re amusing themselves, they take it very seriously. It’s important. It’s just as serious for them now as love will be ten years from now.

I remember when I was little and my parents used to say, ‘Okay, you’ve played enough, come take a bath now.’ I found that completely idiotic, because, for me, the bath was a silly matter. It had no importance whatsoever, while playing with my friends was something serious. Literature is like that—it’s a game, but it’s a game one can put one’s life into. One can do everything for that game.”

Young characters

“When my characters are children and adolescents, I have a lot of tenderness for them. I think they are very alive in my novels and in my stories; I treat them with a lot of love. When I write a story where the character is an adolescent, I am the adolescent while I am writing it. With the adult characters, it’s something else.”

Mixture of people

“Very often there are characters who are a mixture of two or three people. I have put together a female character, for example, from two women I have known. That gives the character in the story or the book a personality that’s more complex, more difficult.”

Characters guide me

“(If I want to thick a character), It’s the characters who direct me. That is, I see a character, he’s there, and I recognize someone I knew, or occasionally two who are a bit mixed together, but then that stops. Afterwards, the character acts on his own account.

He says things . . . I never know what any of them are going to say when I’m writing dialogue. Really, it’s up to them. Me, I’m just typing out what they’re saying. Sometimes I burst out laughing, or I throw out a page and say, ‘There, there you’ve said silly things. Out!’ And I put in another page and start over again with their dialogue.”

I’m very visual when I write

“Often, I have an idea for a story, but there aren’t any characters yet. I’ll have a strange idea: something’s going to happen in a house in the country, I see . . . I’m very visual when I write, I see it all, I see everything. So, I see this house in the country and then, abruptly, I begin to situate the characters. At that point, one of the characters might be someone I knew. But it’s not for sure. In the end, most of my characters are invented.

Now, of course, there’s myself. In ‘Hopscotch’, there are many autobiographical references in the character of Oliveira. It’s not me, but there’s a lot that derives from my early bohemian days in Paris. Yet readers who read Oliveira as Cortázar in Paris would be mistaken. No, no, I was very different.”

I don’t like autobiography

“I don’t like autobiography. I will never write my memoirs. Autobiographies of others interest me, of course, but not my own. If I wrote my autobiography, I would have to be truthful and honest. I couldn’t tell an imaginary autobiography. And so, I would be doing a historian’s job, being a self-historian, and that bores me.

Because I prefer to invent, to imagine. Of course, very often when I have ideas for a novel or a story, situations and moments of my life naturally place themselves in that context. In my story ‘Deshoras’, the idea of the boy being in love with his pal’s older sister is, in fact, based on an autobiographical situation. So there is a small part of it that’s autobiographical, but from there on, it’s the fantastic or the imaginary which dominates.”

I don’t know what’s going to happen in my story

“With me stories and novels, (I) can start anywhere. As for the writing itself, when I begin to write, the story has been turning around in me a long time, sometimes for weeks. But not in any way that’s clear; it’s a sort of general idea of the story.

Perhaps that house where there’s a red plant in one corner, and I know there’s an old man who walks around in this house. That’s all I know. It happens like that. And then there are the dreams. During this gestation period my dreams are full of references and allusions to what is going to be in the story. Sometimes the whole story is in a dream.

One of my first and most popular stories, ‘House Taken Over’, is a nightmare I had. I got up immediately and wrote it. But in general, what comes out of the dreams are fragments of references. That is, my subconscious is in the process of working through a story — when I am dreaming, it’s being written inside there.

So when I say that I begin anywhere, it’s because I don’t know what, at that point, whether is to be the beginning or the end.

When I start to write, that’s the beginning. I haven’t decided that the story has to start like that; it simply starts there and it continues, and very often I have no clear idea about the ending — I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s only gradually, as the story goes on, that things become clearer and abruptly I see the ending.”