The Romanian athlete Iolanda Balaș was an Olympic champion and former world record holder in the high jump. She was the first Romanian woman to win an Olympic gold medal and is considered to have been one of the greatest high jumpers of the twentieth century.

Since the introduction of women’s athletics events to the Summer Olympic Games in 1928, only one woman has been able to win two consecutive Olympic gold medals in the high jump and Iolanda achieved it at Rome 1960 and Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games.

Iolanda dominated high jump for a decade, improving the world record 14 times from 1.75m to 1.91m, and equalled it once outdoors and once indoors to become Romania’s all-time athletics star and inspire generations of young Romanian athletes.

She won 154 consecutive competitions, excluding qualifying competitions or exhibitions between 1957 and 1966. She became the first woman to jump over six feet in 1958. Her technique was a sophisticated version of the ‘scissors.’

Exponential Perfection

Iolanda Balaș was born on December 12, 1936 in Timișoara to a family of Hungarian descent. Her mother, Etel Bozo was a homemaker, while her father, Frigyes, was originally a locksmith. Her father served in the Hungarian Army until he was captured and brought to the Soviet Union and later back to Hungary, where he settled in Budapest.

Iolanda attended the Roman Catholic High School for Girls in her hometown, where sports activities were highly encouraged. Her talent was spotted by the national pentathlon champion Luiza Ernst-Lupsa, who was also a great high jumper and who happened to live in the same building as Iolanda. The young prodigy joined her hometown club to train with Ioan Soter.

Iolanda attended the Roman Catholic High School for Girls in her hometown, where sports activities were highly encouraged. Her talent was spotted by the national pentathlon champion Luiza Ernst-Lupsa, who was also a great high jumper and who happened to live in the same building as Iolanda. The young prodigy joined her hometown club to train with Ioan Soter.

She tried to reunite the family and move to Hungary, but although she managed to obtain a Hungarian passport in 1947, she was not allowed to leave Romania.

Her debut was impressive. She took up the high jump in the late 1940s and secured the first of her 19 national titles in 1951 at just 14. Two years later, in 1953, she followed her coach, who was still an active athlete at that time to Bucharest and transferred from Timișoara club “Electrica” to CSA Steaua.

At 17, Iolanda won silver at the 1954 European Championships in Bern, clearing 1.65m. She followed it up with gold medals at 1958 European Championships in Stockholm and 1962 European Championships in Belgrade.Besides, at the 1959 World University Games in Torino and 1961 World University Games in Sofia she comfortably won gold medals in high jump.

When asked in an interview in 2005 whether she had ever thought about defection, she said that it had crossed her mind; however, as it could have resulted in serious retaliation against her relatives, she did not want to risk it.

In the interview she said: “I feel sorry that I did not win Olympics for Hungary. But a person represents herself and after that a nation. It was not given for me to bear the Hungarian colors, to make happy those who speak my mother tongue. It evolved this way and I feel sorry for it, but I would have gone mad if I would thought constantly about this contradictory situation. I hope that besides Romanians also Hungarians are proud of me.”

Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games

The progression of her stellar athletics career and her life beyond it were all set. When she established the first of her 14 world records clearing 1.75m, the Olympic Games were a few months away and all eyes were on her. The 19-year Iolanda was Romania’s medal hopeful and the favourite to win the Olympic gold.

When it emerged that her coach Janos Soter, whom she would marry after retiring from the sport, had a brother living in Perth the communist authorities banned Soter from travelling, fearing he might defect. Deprived of his expertise and motivational skills, not to mention competing alone on the other side of the world.

So, Iolanda headed to the 1956 Olympic Games without her coach but with the pressure of a whole nation on her shoulders. The US athlete Millie McDaniel was in top shape and she jumped a world record of 1.76m to win Olympic gold. Iolanda finished fifth, and this was to be her last defeat.

Iolanda, stood 1.85m and weighed 72 kgs. She set many records and milestones during the decade in which she dominated the high jump. Significantly, she broke world record in the women high jump 14 times.

Rome 1960 Olympic Games

With 10 world recoards to her name, Iolanda arrived at the Rome 1960 Olympic Games as the ultimate favourite. This time, she was 23, and with some experience in her pocket. It rained in Rome on September 8, 1960, a light, persistent afternoon drizzle that drenched the crowd at a packed Olympic stadium and saw athletes and officials alike drifting ethereally around the arena in clear polythene hooded robes.

With the bar set at 1.73m, the Olympic high jump final had come down to the last three competitors. The Pole Jaroslawa Jozwiakowska, wearing a shoe on her left foot but keeping her right foot bare, went first and failed. Then Dorothy Shirley of Great Britain also failed. Iolanda Balaș slipped off her waterproof, unzipped her tracksuit top, slipped out of the trousers, adjusted her red vest and blue shorts and walked lightly to the end of her run-up. Six bouncing, skipping steps and over she went, finding the height so comfortable to clear she even landed on her feet in the sand.

Iolanda was guaranteed Olympic gold after clearing 1.73m from her first attempt. Her two challengers each had two more attempts to stay in the competition; neither of them was successful. The Romanian swept the damp ash of the run-up area, then cleared both 1.75m and 1.77m with her first attempts. Then the bar was raised to 1.81m, over which she went with her second try. Up went the bar another to 1.85m, a new Olympic record height. After two failures Iolanda stood at the end of her run and paused for a moment, shaking out her arms.

A couple of short steps, a skip, two longer steps and she launched from her left foot. Up swung her right leg until it reached the height of the bar when her right foot shot out into the air beyond, pulling the rest of her behind it. Iolanda rolled her body slightly to the left, lifted her other leg over the bar, briefly thrust out her arms for a final push through the air and down she went into the sand. She bounced immediately to her feet, left arm raised in triumph. It already seemed an age since her nearest rivals had struck out of the event’s showpiece final.

That performance on a drizzly afternoon in 1960 was arguably the greatest illustration of her complete dominance of the sport. Her winning margin, 14 centimetres ahead of her nearest challengers, has never come close to being equalled. Her performance was a pure display of athletic greatness and grace. Her only competitor was herself. No other athlete has dominated this event as she did.

When Iolanda hopped onto a rain-spattered podium in Rome, bent to receive her medal then waved to the crowd, in the television arc lights her face seemed to glow with a golden hue, shining beneath the grey clouds. The packed arena rose to her as one, the sheer bounding exuberance of her pride lighting up the gloominess of the conditions and an Olympic crowd recognizing one of the genuine greats. Iolanda’ achievements might have seemed superhuman, on that Roman podium she even looked superhuman.

Only a few days earlier there had been a chance Iolanda might not make the games at all. She was fit, in the form of her life and practically guaranteed to bring home the gold medal, yet the authorities in Bucharest seemed determined to make things as difficult as possible for her.

Nothing could detract from the elation of winning, however, even if she was effectively competing only against herself. Of all the titles, all the medals, all the achievements of a stellar career, that afternoon in Rome gave Iolanda the most satisfaction.

She said, “I felt an incredible degree of satisfaction, it was an elevated moment. They say that before death your life flashes before you. That happened for me right after my victory. My loved ones, my setbacks, my joys, my hopes, it all flashed in front of me. It was like watching a film of my own happiness and I think that’s the moment when my life truly began.”

Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games

Iolanda won a second gold medal at the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, with a winning jump of 1.90m, 10 cm better than the silver medalist’s mark. When in 1958 she became the first woman to clear six feet (1.83m) it was six years before another woman did the same. She remained undefeated in all competitions for ten years between 1957 and 1967, winning 154 consecutive competitions, and her final world record of 1.91m, set in 1961, a record that remain stood for a decade.

Despite Soter having no close relatives in the area this time he was again refused permission to accompany Iolanda to the games. Determined not to miss out on another gold, Iolanda stayed in Romania as late as possible to keep training with Soter, not travelling with the rest of the Romanian delegation. As her delayed departure date approached, Iolanda grew so exasperated she decided to take matters into her own hands. “If [Soter] had to stay in Bucharest again I knew it would be fatal for my chances,” she recalled.

Despite Soter having no close relatives in the area this time he was again refused permission to accompany Iolanda to the games. Determined not to miss out on another gold, Iolanda stayed in Romania as late as possible to keep training with Soter, not travelling with the rest of the Romanian delegation. As her delayed departure date approached, Iolanda grew so exasperated she decided to take matters into her own hands. “If [Soter] had to stay in Bucharest again I knew it would be fatal for my chances,” she recalled.

“So, on the spur of the moment, I went to the government buildings and ran into Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, the secretary general of the Romanian Communist Party. He was so surprised by my determination to find him – the policeman on the door had no chance of stopping me – he was lost for words. I told him I was done; I wasn’t going to travel to Rome because it made no sense to represent a country constantly distrustful of me.”

Gheorghiu-Dej promised to look into the matter and within a couple of days Soter’s travel ban was lifted, although the pair would be accompanied at all times by a member of the secret police.“They watched every step we took but that didn’t bother me,” said Iolanda “I would have been much more tense if I didn’t have my coach there, someone I trusted to share my thoughts.”

Iolandawas born in Timisoara of Hungarian heritage but grew up separated from her father. He fought in the Hungarian forces during the Second World War, was taken prisoner by the Russians and by the time he was released back to Hungary the border with Romania had been closed. It left her with a strong sense of her Hungarian identity despite living in and competing for the country of her birth.

“I was the first Romanian woman to win gold at the Olympics, but I was also Hungarian,” she recalled in 2005. “I feel sorry I did not win the Olympics for Hungary but an athlete represents herself first, then a nation.”If there was one advantage to being born in Timisoara it was that by chance the caretaker of the building where Iolanda and her mother lived was Luiza Ernst-Lupşa, a well-known athlete who had been Romania’s pentathlon champion in 1948. She spotted her talent when she was as young as nine and was able to provide invaluable guidance.

She had hoped for a third successive Olympic gold in Mexico 1968 Olympic Games, but a persistent heel injury force Iolanda to retire in 1967, ending a decade of dominance almost unparalleled in any event in the history of athletics.”Sometimes I found it hard to compete,” she admitted, “there was just no opposition for me.”

Giving Back to the Sport

Her string of victories continued until 1967 and her career ended in 1967 due to an achilles tendon injury. After retiring from competition in 1967, Iolanda married her former coach Ioan Soter in 1967, and transitioned to become a physical education teacher. They were blessed with a son, Doru, who is still involved in Romanian athletics.

She found herself in managerial positions in the sports industry, serving as the President of the Romanian Athletics Federation from 1991 to 2005, and vice president of the Romanian Olympic Committee from 1998 to 2002.

She was also a member of the technical committee of the European Athletics Association, and in 1995 was elected to the women’s commission of the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF).Iolanda also believed in the power of media and wanted to shed light on Romanian athletes. She initiated the appearance of the magazine Romanian Athletics.

She believed in the power of sport and in investing in the younger generation. She built sporting facilities in Romania which were named after her. She was awarded the Emeritus Master of Sport, the Romanian Steaua Order, the Order of Sports Merit, the National Order of Steaua Romaniei (officer) and the Golden Column, which is the highest distinction of the Romanian Olympic Committee.

Iolanda was diagnosed with type II diabetes several years before her death and was hospitalized several times. Iolanda died at the age of 79 following gastric complications on March 11, 2016 at Elias Hospital in Bucharest, Romania. She is buried at Ghencea Cemetery in Bucharest.

Her memory still lives through the Romanian athletes, the facilities she created and the legacy she left behind as the best high jumper of her era. Her son, Doru, defines her as “The Smile of Romanian Athletics History.”

(The author is an Associate Professor, International Scholar, winner of Presidential Awards and multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. His email is [email protected])

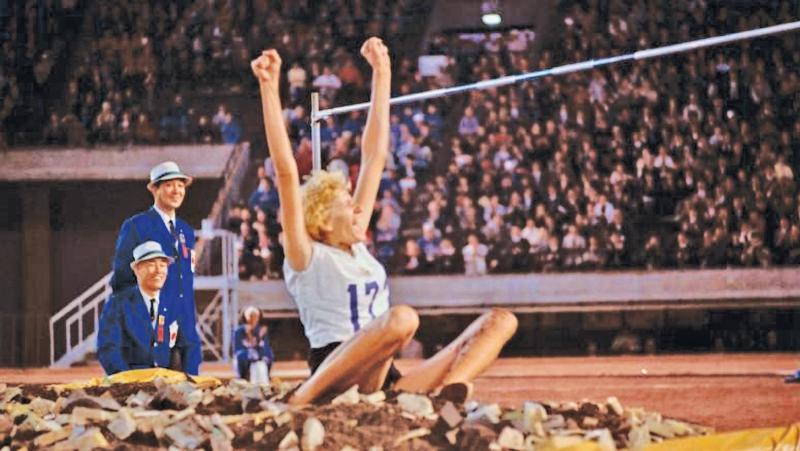

Iolanda in action at Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games