V.S. Naipaul is a conservative, bigoted, irascible, and yet, one of the most astute observers of the human condition. He was an old bigot. He wrote good books and then took to bigotry or so one could begin to remember him as homage to his talent for devastating putdowns, no matter the occasion.

Naipaul’s essay when Nirad C. Chaudhuri, another writer of self-deception, passed away in 1999 began thus: “Nirad appropriate and also Chaudhuri was an old fool, he wrote one good and unexpected book, the autobiography of an unknown Indian, and then took to clowning.”

Naipaul’s essay when Nirad C. Chaudhuri, another writer of self-deception, passed away in 1999 began thus: “Nirad appropriate and also Chaudhuri was an old fool, he wrote one good and unexpected book, the autobiography of an unknown Indian, and then took to clowning.”

To write a similarly uncharitable opening line – one filled with casual cruelty, an arrow in the Naipauline quiver is easy. Perhaps it has already been written and is staple wisdom for many people. What is harder is to recognise that this kind of unthinking mimicry and virtue signalling that masquerades as sophistication was what he described unsparingly for nearly 60 years of his career.

The result is familiar. His detractors are plenty, indignant at his refusal to play by their rules. His admirers caveat any declaration of admiration by proxy, and political forces opportunistically and also abandon him when his writings ill fit their needs. But all that is to be expected especially when one is perched as high as he was on the greasy pole of world literature.

Irascible sage

From that zenith, with a Nobel Prize and a Booker in hand and his armada of 30-odd books, have duly played the role of an irascible sage at literary festivals where he provided requisite provocation for feminists, secularists, and the all too conveniently triggered, yet amidst these festivities, there remains the disquieting fact that by the end of his life, I am afraid Naipaul had become a dispenser of sound bites who bowdlerised the hard earned insights from his own ambitious, many layered, unrelentingly observant, and carefully crafted books.

Since his passing away, one is struck by the copious amount of commentary that has been entirely biographical focusing relentlessly on the tawdry and unsavoury, these articles put his books on the back seat. Over his literary life, Naipaul’s subjects in the books and essays he went back to them time and again. His life was spent not just in the company of words or his self but also in engagement with the world at large.

Naipaul’s literary genius, or sleight of hand, was to recognise that by chronicling the list of self-deceptions and self-promotions of persons, one could indict or characterise entire societies for the same failings. Nowhere did he do this more precisely than in his three books on India, a country that he realised stripped him of his own illusions about his ancestry.

The India of the early 1960s that Naipaul arrived into was a despairing and hungry country while still being ruled by Anglicised brown-skinned Sahibs who were great dispensers of borrowed profundities.

India as a phenomenon confounded Naipaul the artist. In that he found it difficult to identify a form and tone commensurate with the tumult of his feelings.

Eventually, his writings on the topic became in book form an area of darkness and India as a wounded civilisation. Despite many reservations, Naipaul ended his last Indian book recognising that India had somehow managed to survive, thanks to millions who simply did their ordained or mandated part in life.

Notwithstanding this sliver of cautious optimism, he noticed that out of the encompassing humiliation of British rule, there will come to India the idea of country and pride and historical self -analysis.

Naipaul has written two books about his Islamic excursions through Iran, Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia. He articulated a thesis which he summarised as “the cruelty of Islamic fundamentalism is that it allows only to one people – the Arabs, the original people of the Prophet – a past, sacred places, pilgrimages and earth reverence.

He argued that the internationalisation of Arab superiority in the minds of converted people produced a form of mimicry, an abandonment of their own histories, and ultimately a wilful misreading of their own past. In response to his books, there followed a barrage of criticism that earned him the reputation of a bigot.

British writer

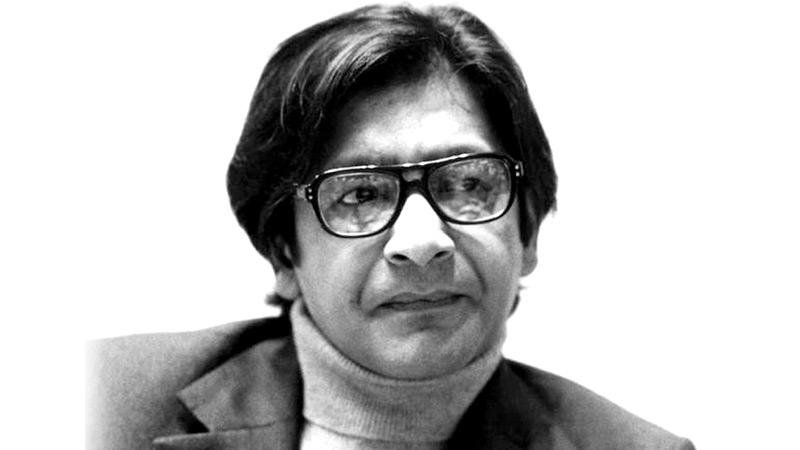

Sir Vidiadhar Suraj Prasad Naipaul, well-known as V.S. Naipaul, was a Trinidad and Tobago born British writer in English. His writings were greatly admired but his views sometimes aroused controversy. He published over 30 books of fiction and non-fiction over 50 years. In the late 19th century, Naipaul’s grandparents had emigrated from India to work in Trinidad’s plantations.

Naipaul was born to Draupathy and Sree Prasad Naipaul on August 17, 1932 in Trinidad. His father Sree Prasad was an English-language journalist. According to his genealogy, the Naipauls were Hindu Brahmins. In the 1880s, Naipaul’s paternal grandparents had emigrated from India to Trinidad. During that time, many Indians who were affected by the famine of 1876-78 had emigrated to distant outposts of the British Empire.

Naipaul’s views about Mahatma Gandhi were somewhat controversial. He wrote, “When India became independent and Gandhi was dead, I read his autobiography. I saw its strange deficiencies, the absence of landscape, extraordinarily narrow view of England and London. No attempt has been made to describe the great city that must surely have overwhelmed the young man from Rajkot in Gujarat.

He had missed theatres and music halls in his quest for vegetarian food and in his wish to stay faithful to the three vows he had made to his mother before leaving Rajkot: No meat, no alcohol, and no women.” He called Gandhi “The least Indian of Indian leaders. He looked at India as no other Indian was able to do. His vision was direct and revolutionary.”

For Naipaul, all knowledge is universal and he wanted people to know themselves. Charlie Rose, an American broadcaster asked Naipaul, “Do you think about dying?” Naipaul paused for a moment and said, “I think it would be a relief.”

Naipaul won the Booker Prize in 1971 for his novel ‘In a Free State’. He was knighted in 1990 and he won the prestigious Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001.

He lived writing, travelling, and stirring troubles in the name of truth. After facing many storms in life, he died peacefully at his home in London on August 11, 2018. The Guardian paying him a great tribute said, “He was sceptical, enquiring, sharply observant and unfailingly stylish.” The New York Times said, “Naipaul had the coolest literary eye and the most lucid prose style.”

The writer is a freelance journalist and Indologist based in Hyderabad, India.