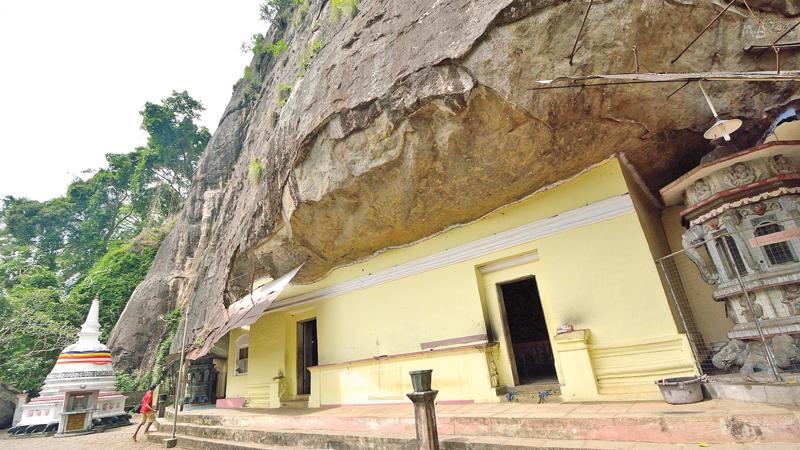

Mulgirigala (more commonly called Mulkirigala) is an imposing and historical rock cave temple in the South, to which the Dutch gave an exaggerated attention, within their territory. Mulgirigala Vihara is one of the oldest and most revered temples in Southern Sri Lanka.

The Mulgirigala Raja Maha Vihara is 13 kilometres away from Beliatta in the Hambantota district. There are two main roads that give access to the Mulgirigala Vihara. It can easily be reached by making a 30-minute journey inland from either Dikwella or Tangalle.

The other road runs inland through Middeniya – Wiraketiya. We drove down this road because it was the easiest and shortest approach to Mulgirigala from the Julampitiya-Weeraketiya road. It was just a 45-minute journey.

The Mulgirigala Raja Maha Vihara is a 3nd Century BC Buddhist cave temple complex that ascends and crowns this rock, and which gives the place its aura of sanctity. It is a temple of great antiquity and famous for its fine murals of great historical significance. Surrounded by a plain landscape, Mulgirigala is deemed to be the tallest rock, reaching majestically up to the sky for over 200 metres.

Seven terraces

The peak is almost as isolated and stunning as the better-known Sigiriya. A flight of 533 steps, starting from the lower terrace of the Vihara, guides pilgrims to reach the seven terraces which comprise rock cave shrines with reclining Buddha statues and beautiful murals belonging to different periods.

The peak is almost as isolated and stunning as the better-known Sigiriya. A flight of 533 steps, starting from the lower terrace of the Vihara, guides pilgrims to reach the seven terraces which comprise rock cave shrines with reclining Buddha statues and beautiful murals belonging to different periods.

The ascent to the terraces is very steep and at one place, an almost perpendicular series of steps must be climbed with the aid of an iron rail. The final flight of steps, carved into the rock boulder leads to the summit terrace of Mulgirigala, on which stands an ancient Dagaba and an image house. The view is breathtaking as it cannot be replicated anywhere else in the island.

It was at Mulgirigala where a scholarly English colonial administrator named George Turnour who was Government Agent for Sabaragamuwa in 1826, made a discovery of the monastic library which had the olas containing the ‘key’ to the translation of the Mahawamsa, in 1838. These Pali chronicles had recorded the island’s story from 543 BC to modern times. Turnour’s discovery of the Tika – the commentary made the translation of this ‘Great Chronicle’ first into English and some years later into Sinhala possible.

The origins of Mulgirigala are obscure. Though it is not mentioned in any of the ancient chronicles, it has been the abode of Bhikkhus from very early times.

This is proved by the three Brahmin inscriptions carved along one of the drip-ledge rock caves of Mulgirigala. The general belief is that the Mulgirigala Vihara was founded by King Saddatissa (137-119 BC) who built Dakkhina-giri Vihara. Dakkhina-giri means ‘rock in the South’ and this may well have been the earlier name for Mulgirigala.

An interesting legend is associated with the name of Mulgirigala. Two indigenous persons who had seen the rock while hunting informed the King that there is a suitable place to build a temple. The King taking heed had gone to the place for inspection and commented Mu kivu gala hondai (the rock that he suggested is good). It is thought that this phrase has later evolved to Mu Kee Gala, Mu Kiri Gala and then to Mulgirigala.

During the hey days of colonial administration, many Europeans did make an effort to visit the site and wrote highly informative travellers’ accounts of Mulgirigala. One such traveller was Englishman, James Cordiner who published his travel account in his book, A Description of Ceylon, in 1807. In their accounts, they described their experience in wild animal infested jungles with their journeys made during the monsoon season in a rugged land.

Mulgirigala was popular among the foreign writers in the colonial period. Albrecht Herport, a Swiss who served as a soldier in Sri Lanka in 1663, and a German, Daniel Parthey in 1678 both wrote about Mulgirigala.

They give details regarding images, figures and inscriptions at Mulgirigala. Christoph Langhansz, a German soldier in the Dutch service, wrote in similar fashion after a brief stay in 1695.

It is said that in colonial times, there was a village known as Kahawatta close to Mulgirigala from where a rising rock of Mulgirigala was more visible and a small cottage gave accommodation to travellers. Visitors of the bygone era would have been able to view the rock from Kahawatta.

Today, one can’t catch a glimpse of Mulgirigala until one reaches the foot of the rock, due to the stretch of coconut palm cultivations.

Dutch interest

The Dutch rulers gave Mulgirigala an exaggerated attention. A Dutch soldier wrote in 1663: “One sees the image of Adam formed of earth, of remarkable size, lying on the hill.” So, it was that the Dutch came to believe that Adam’s ashes were buried at Mulgirigala and that the large reclining Buddha statue enshrined at one of the caves at the Vihara represented Adam.

So, the Dutch started to call Mulgirigala by the name Adam’s Berg (or hill) and it came to be confused with Adam’s Peak, the sacred mountain known as Sri Pada lying so many kilometres to the Northwest in the Sabaragamuwa Province.

The dramatic isolation of Mulgirigala made it one of the most painted sites of the colonial period. The Dutch interested in Mulgirigala had a fortunate consequence for historians, as Governor Domburg sent renowned artists, Arent Jansen and Jan Brandes, to sketch the Mulgirigala statues, the rock and the countryside nearby.

Jansen and Brandes took the commission very seriously and had a hut built at the foot of the rock so that they could reside there. Jansen’s series of detailed paintings are the earliest visual representation of Mulgirigala and demonstrate that, at the time, the rock could be seen from far away.

Incidentally, it was not until 1766 that Governor Falk realised that the Dutch had muddled the story surrounding Mulgirigala and dropped the name Adam’s Berg.

It is assumed that the revival of Mulgirigala can be attributed to many Kings while the present reputation of the Vihara was earned during the reign of Keerthi Sri Rajasingha of Kandy.

Seven cave shrines

Today, Mulgirigala comprises seven cave shrines, namely, Mahanaga Vihara, Paduma Rahath Vihara, Meda Malu Vihara, Raja Maha Vihara, Aluth Vihara, Naga Vihara and Pirinivan Vihara. Perhaps, the most unique aspect is the exquisite mural paintings within the caves, said to have been painted during the Kandyan era with a combination of Kandyan and Southern techniques of expert hand artistry that has recounted Jathaka stories of the Buddha, showcasing the brilliance of ancient artists and their creativity. At one of the walls of the Rajamaha Vihara, where a unique mural painting was illustrated, the depiction of women playing drums is said to be found only in Mulgirigala.

After visiting all seven rock cave shrines, we returned to the lower terrace known as Siyabala Maluwa where we stepped into a museum of the Vihara, at the foot of the rock and near the entrance of Mulgirigala Vihara. It houses numerous artefacts found during the Dutch period and beyond.

Among the most valuable exhibits is an ancient VOC emblem engraved land deed which was bestowed to the Mulgirigala Vihara by Dutch Governor in 1766. Among other exhibits are several VOC coins and ancient ola leaves.

Mulgirigala is a unique place to recall the legacy of the country and its history, and has always been a prime destination for discerning travellers. Although the trek is somewhat arduous, the discovery is worth the effort. At the foot of the rock, plenty of Belimal and wood apple drinks are available to quench your thirst after the hectic climb.