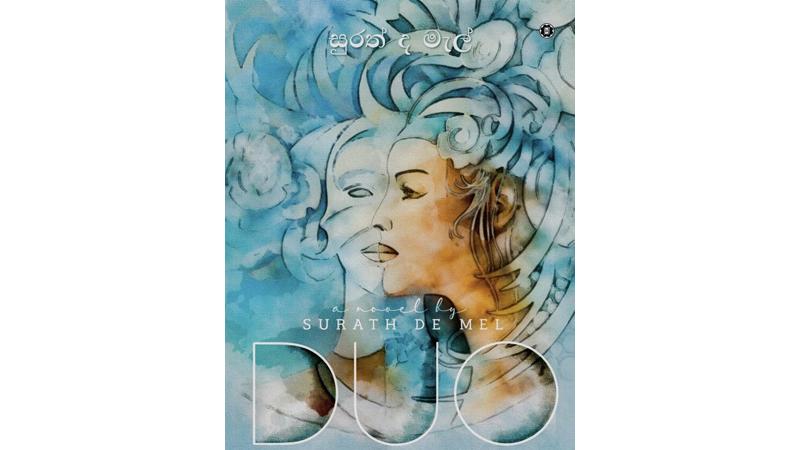

Books are meant to be read. And a few of them make you contemplate. They reverberate in your mind as your favourite songs do. Young Surath de Mel’s books belong to this second category. This he has proven time and again. His latest (Sinhala) novel “Duo” is a testimony to that.

De Mel seems to have a special predilection (and a skill) to cross the gender boundary a male writer is otherwise biologically unwonted to. Whether he does this as good as (or better than) a female writer will be best answered by a biological female, who only experiences the subtle sensitivities associated with her biological cycle – physical and emotional. Had de Mel been able to cross that frontier successfully?

This time around too he has selected female characters (Uma, Depika and Sarah) as his key figures as he had done before in “Thee ha tha” (Divya) and “C+” (Dil, Manasi and Muthu). These characters are placed either side of the Palk Strait in two mutually exclusive stories, running parallel to each other with a time gap of at least two decades.

Doing so he has harped on a wide array of issues ranging from rape, sexual violence and sex work to bisexuality, queerness and crossdressing, all considered contentions in conventional societies. He also surfaces the issue of “eye rape” – it would be interesting to see how male folk comprehend this. He has navigated these themes with immaculate precision and authority carving a special niche for himself in the contemporary Sinhala literary arena.

What makes de Mel’s writing unique is multifaceted. One is his mastery of the Sinhala language. Second is his bilingualism. Third is professionalism in his writing. His meticulous research into the nitty gritty of details related to the locations and events, both in Sri Lanka and Kerala is a lesson for anyone who wishes to be a good writer.

The ease at which De Mel engineers the language in an unassuming and carefree manner pathognomonic to him emanates from his priviness to a vast vocabulary. His knack to twist and turn a sentence to expose its under belly is complemented with the use of homonyms and homophones with precision.

Common thread

Parallel stories in literature are few and far between, for the difficulty of imagination and complexity of finding a common thread that binds them. Alexandre Dumas’ “The Corsican Brothers” and Mark Twain’s “Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins” are noteworthy specimens. These examples will shed light on the calibre of creators who would dare to lay their hands on a venture of this nature.

Apart from de Mel’s gusto to venture into new vistas, his latest product demands due recognition for a number of reasons. On the gender scene, he introduces some aspects that definitely need due attention in the present socio-political context in the country. Victim blaming, self-blaming, post traumatic stress disorders and rape victim empathy scale are concepts that surpass the mere literary domain and hinges on the wider socio-political arena. De Mel’s attempt to present these in a technical milieu that is literarily palatable is commendable.

De Mel takes the two-pronged civil conflict of the 80s by its horns. He exposes with impunity how both these scenarios, the protracted civil war in the Northern theatre and the 88-89 beeshanaya in the South, eroded the social fabric of the Sinhala Buddhist society with indelible consequences. The tragedy that befell Uma’s family in the aftermath of 88-89 was inconceivable. Her entire family sans herself is decimated within a few months, leaving her destitute.

The intensity of the “sibling rivalry” that prevailed during 88-89 was alarming. It was so intense that the siblings of the same household were pitted against one another in the lines of “defined” and “re-defined” patriotism. As a result, while the elder brother loses his life battling an ethnic war in the North, the younger brother is killed in the South by the same military his brother was part of.

Socio-political calamities

For a poor, powerless Sri Lankan rural woman encountering serious socio-political calamities, things may not have changed much compared to the time of Leonard Woolf (in “The Village in the Jungle”, in 1913) from today. The sorry tale of a rural Sri Lankan woman sandwiched between violence and sexual exploitation with lack of options for her survival remains pretty much the same.

Once all survival strategies are exhausted, similar to Punchi menika falling prey to the sexual urges of Fernando mudalali hands down in Beddegama, Uma too is left high and dry but to find solace in sex trade.

It is intriguing that her gravidity makes her a preferred choice among her customers. Misery associated with violence and death in Sri Lankan society is well encapsulated in Uma’s utterance to the abortionist, whose services she was made to seek at some point in time.

“Doctor, my brother is in the Army. My other brother was killed by the Army. My sister hanged herself. Seeing all this, my father died of grief. The fellow responsible for my sister’s death too was killed. Unless you finish this off, I too will kill myself”. How common a commodity the death had been during that time in our society.

Duo is not only a novel experiment, but also a novel experience, for the writer as well as the reader. How two parallel stories of two different timelines and countries flow uninterrupted to be interwoven at the end is phenomenal.

The reader is kept in suspense as to the logic of this whole experiment till he reaches the penultimate page, when he is greeted with a “wow”.