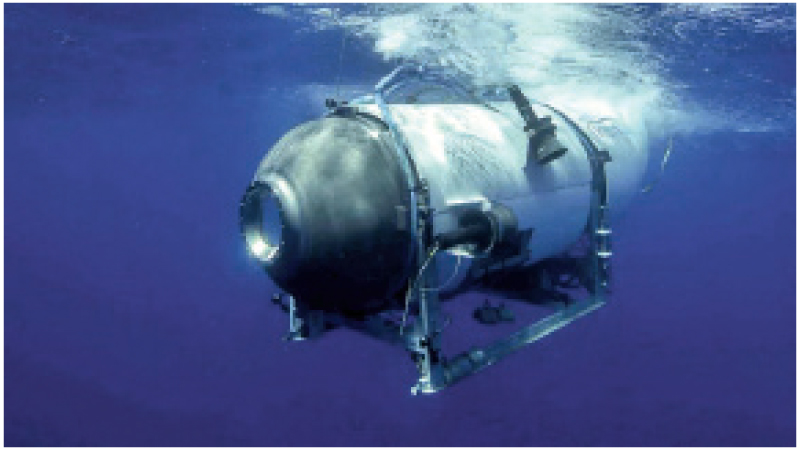

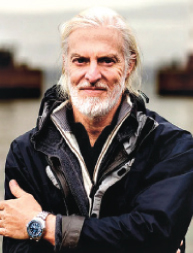

One year ago, the Titan submersible was destroyed on an ill-fated mission to the wreck of the Titanic. Ocean explorer Victor Vescovo explains why the mishap could make future deep-ocean voyages safer.

It has been a year since the submersible Titan imploded at the site of the RMS Titanic. Two of my friends and colleagues, P.H. Nargeolet from France and Hamish Harding from the UK, were onboard. I worked extensively with PH for several years on the design and operation of the ultra-deep diving submersible Limiting Factor, while Hamish and I visited the deepest point in the ocean, Challenger Deep, together. Their loss was not just a big news story: to me, it was personal.

It has been a year since the submersible Titan imploded at the site of the RMS Titanic. Two of my friends and colleagues, P.H. Nargeolet from France and Hamish Harding from the UK, were onboard. I worked extensively with PH for several years on the design and operation of the ultra-deep diving submersible Limiting Factor, while Hamish and I visited the deepest point in the ocean, Challenger Deep, together. Their loss was not just a big news story: to me, it was personal.

A year later, many ask: “How has the incident changed deep-water exploration?”

There are two answers.

The first is: “I very much hope, not much.”

By that I mean that I sincerely hope that this incident does not make people more fearful of diving into the depths of the extraordinary ocean, the lifeblood of our world. Three-quarters of the world’s ocean is completely unexplored, home to multitudes of undiscovered species, to geologic puzzles that can help us understand seaquakes and tsunamis, and possibly insights into how the world is affected by climate change.

Unfortunately, the sensationalism surrounding the accident and the instinctive fear many people have of the deep ocean have perhaps made some of those unfamiliar with submersibles more anxious about getting into one.

But this absolutely should not be the case; just as people should not stop travelling by air after they hear reports of a fatal aircraft accident. Those of us in the submersible community – the builders, pilots, and researchers – have not hesitated in continuing to extensively dive in these vehicles, which should give everyone else confidence in their safety.

Unfortunately, the founder and chief sub pilot of OceanGate, Stockton Rush, dismissed safety concerns as standing in the way of innovation and his ambition of establishing a viable commercial operation. He used carbon fibre so that he could construct a vessel big enough to carry sufficient passengers to pay for the high costs of building and operating a deep-diving submersible.

Those compromises for the sake of economics, and potential technological bragging rights against what he perceived as an overly conservative industry, proved fatal.

Historical similarities abound. The Titanic did not adequately heed warnings of extensive icebergs on its route, just as Oceangate ignored warnings of its flawed design.

The Titanic had insufficient lifeboats because more would have allegedly cluttered the deck and ruined the view for passengers, while the Titan used carbon fibre so more people could be fitted into it. And there was of course, the never-ending tale of hubris: Titanic was “too big to sink” and the Titan was to be a “revolutionary”. Both were deemed perfectly safe by their owners and yet they both were not. At all.

There is a second way the loss of the Titan could affect deep ocean exploration. The accident, in an almost eerie way, repeated many of the elements that contributed to the tragedy of the Titanic over a hundred years before it. However, the disaster could – and should – have a similar positive effect on future worldwide safety regulations.

There is a second way the loss of the Titan could affect deep ocean exploration. The accident, in an almost eerie way, repeated many of the elements that contributed to the tragedy of the Titanic over a hundred years before it. However, the disaster could – and should – have a similar positive effect on future worldwide safety regulations.

In the wake of the loss of the Titanic, strict Safety of Life at Sea (Solas) regulations were created and endure to this day. These stringent regulations govern the equipment, procedures, and training that are required to operate commercial vessels at sea. Therefore, the loss of Titanic, as tragic as it was, saved significantly more lives in the aftermath by spurring new safety measures to prevent a similar tragedy from ever happening again.

So, too, is the glimmer of hope from the Titan disaster. While we still await the results of two official investigations into the accident by the US Coast Guard and the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, there are calls to tighten the safety measures in the submersible industry. “Non-classed” submersibles (that is, not certified by accredited third parties) should never be allowed to transport commercial passengers.

Like in aviation, experimental craft can and should be allowed to operate so that we may push the boundaries of technology, safety, and capability, but people who have no idea how to calibrate the risks they are taking should not be able to buy tickets to travel in experimental craft.

Simply signing a waiver, skirting the law by operating in international waters, or using legal judo to classify commercial passengers as “crew” when they clearly are not, shouldn’t shield risky operators from prohibitions on operating as well as retroactive legal action when they come back to any port.

BBC