For the non-Chinese, Hanzi characters have always been daunting – held as mysterious symbols of aesthetic beauty; to the point that some have ill-advised tattoos in Chinese that says “Electricity” instead of “Power”.

For the non-Chinese, Hanzi characters have always been daunting – held as mysterious symbols of aesthetic beauty; to the point that some have ill-advised tattoos in Chinese that says “Electricity” instead of “Power”.

But beside the pretty strokes and strange appeal, a careful study of a language reveals far more about a culture than one can ever imagine.

Man in a box

Sun Zhiyi

For example, I noticed something peculiar while re-watching the Water Margin.

In one scene, instructor Lin Chong wears a convict’s coat emblazoned with the character qiú, meaning ‘prisoner’. What struck me was its composition: the character rén – person enclosed inside wéi – enclosure). It was visual poetry — a man trapped in a box.

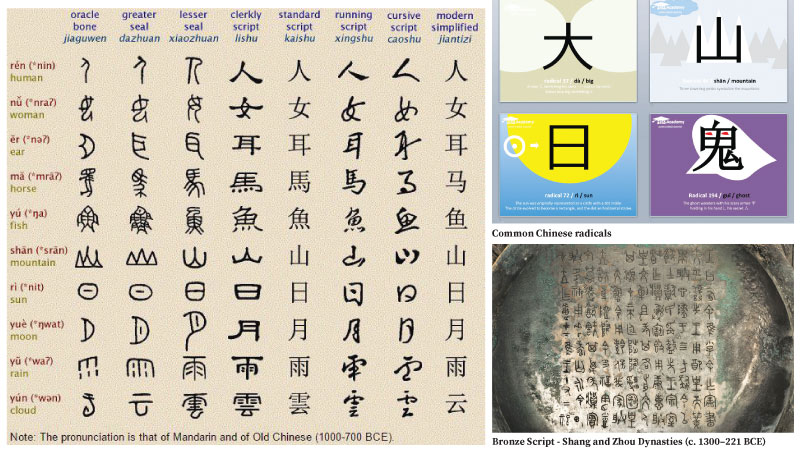

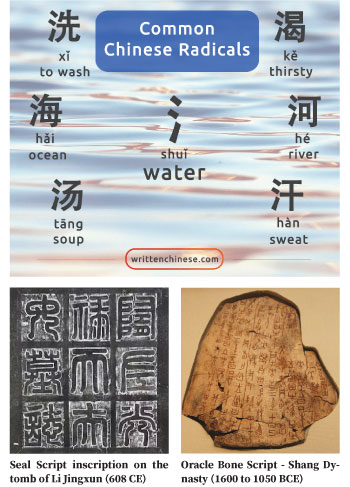

This led me down a rabbit hole. I learned that Chinese characters are often built using radicals — root components that hint at meaning or pronunciation. There are over 200 radicals in common use, and they function like semantic building blocks.

Yet, oddly enough, “rén wéi” — the literal characters for “person” and “enclosure” — doesn’t actually mean anything when combined that way. That’s when I realised: this language isn’t just phonetic, it’s pictorial, historical — and sometimes, deeply ironic.

And don’t get me started on the bewildering number of sounds transliterated through Pinyin, the standard Romanisation system for Mandarin. Take the “ch” sound. In Pinyin, it might be written as “ch”, but also “zh”, “qi”, or even “ji”. So, if you’re trying to say “cheese,” you might end up saying “knees.”

Last but not least, let’s not forget about the clueless foreigner who once asked, “How are you horse?” in Mandarin since the “ma” in “ni hao ma?” can easily mean ‘mother’, ‘hemp’ or ‘horse’ if you are unaware of tonal differences.

But instead of giving up, I did what any curious outsider would: I turned to experts — hoping they could translate not just the language, but the culture encoded within.

Oracle Bones

Sun Zhiyi (English – Susan) is a university student in Beijing. She created a YouTube channel called ‘Hanzi Unfolded’ to explain the evolution of Chinese script to foreign audiences.

The earliest form of written Chinese was a pictograph etched on turtle shells and animal bones that came to be known as ‘Oracle Bone Script’. They were discovered in 1899 by Wang Yirong at a pharmacy when he noticed patterns on the back of turtle shells that hadn’t been ground into powder. These patterns looked like primitive writing.

“For over 3,600 years, they’d been sleeping quietly beneath the land of China, a far-off script that the Chinese had always imagined. Because they were hidden away for so long, there wasn’t enough physical evidence about where Chinese characters came from. There was a big gap in how they evolved, and a huge blank in the study of Chinese characters,” Susan said.

However, the original purpose of bone script was for divination. During the Shang Dynasty (1600 to 1050 BCE), shamans would engrave pictographs on turtle shells to inquire about various matters, Susan said. They’d consult about wars, agriculture, and royal court activities.

“The concerns recorded in oracle bone divinations weren’t limited to state affairs alone. During the reign of King Wuding of the Shang Dynasty, his wife name Fu Hao was mentioned nearly 200 times in oracle bone inscriptions. Questions like, “Has Fu Hao’s toothache eased?”, “Will Fu Hao face a difficult childbirth?”, and “Fu Hao has been feeling weak lately. May the ancestors protect her and help her recover soon” were all inscribed,” Susan said.

Timeline

I asked her how the language evolved from these primitive etchings.

“Let’s take the character ‘good’ as an example. In oracle bone inscriptions, ‘good’ depicts a woman holding a child. The birth of a new life is, of course, a good thing,” she said.

Oracle Bone inscriptions during the Shang Dynasty – pictographic; used for divination, carved on turtle shells and animal bones.

Then, bronze inscription during the Shang and Zhou Dynasties (c. 1300–221 BCE) – Inscriptions on bronze vessels, with a stable structure.

Next came the Small Seal Script during Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) – Standardised by Li Si, featuring uniform strokes, and unifying writing styles.

In 221 BCE, Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the same ruler who started constructing the Great Wall, sought to unify the written language. He chose Small Seal Script as the gold standard, ending the quirky, diverse characters from the six States.

“It was like a magic wand that made sure imperial orders, laws, and official papers could zoom around the vast land without any hiccups. This cultural integration, though politically motivated, was like a superglue that held the threads of Chinese civilisation together, allowing the Chinese character system to not just survive but thrive and evolve.”

“It was like a magic wand that made sure imperial orders, laws, and official papers could zoom around the vast land without any hiccups. This cultural integration, though politically motivated, was like a superglue that held the threads of Chinese civilisation together, allowing the Chinese character system to not just survive but thrive and evolve.”

“Small Seal Script’s structural wisdom—the brilliant system of radicals—became the blueprint for all future Chinese characters,” Susan said.

Then came Clerical Script of the late Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE), Characterised by square – turned strokes, “silkworm’s head and wild goose’s tail” shapes, marking the beginning of modern-style writing.

This was followed by Regular, Running and Cursive scripts of the late Han Dynasty to the present day (220 CE–present).

Simplified Chinese was introduced in the 20th century; these are cut down characters in terms of strokes, widely used in mainland China.

Radicals and phono-semantics

Unlike alphabetic writing systems, the composition of Chinese characters is like Lego blocks, Susan says. Elements like “mountain”, “water”, “sun”, and “moon” all serve as radicals that the ancients used to express various things in the world. This unique way of character building gives Chinese characters both visual symbolism and logical combinatorial properties.

There are characters that directly outline shapes, such as “mountain”, which resembles peaks and ridges.

There are also characters that convey abstract concepts through the combination of components, like “rest”, which depicts a person leaning against a tree to take a break.

It’s incorrect to say that Chinese characters are purely pictographic. Phono-semantic compound characters account for over 80 percent of all Chinese characters. Half of them indicate meaning, while the other half represents sound. It’s worth noting that the phonetic part also carries semantic implications.

Take the character “clear” as an example. Its semantic radical is “water”, suggesting things or concepts related to water. The phonetic radical is “qīng”, which not only indicates the sound but is also an independent character meaning a colour, either blue or green, with an underlying sense of “purity and brightness.” When combined with the water radical, it conveys the idea of water being clear, transparent, and free of impurities.

“How did the ancients depict “morning”? In Oracle Bone script, the character “morning” is composed of the symbols for “sun” and “grass.” In the early morning, one would see the sun slowly rising above the low-lying grass in the distance. There’s another character that deeply moves me — “admiration”. In Oracle Bone script, it portrays a person standing reluctantly in the wilderness, watching the setting sun gradually disappear behind the grass, a scene brimming with infinite longing and yearning for dusk,” she says.

‘God’s piano

Given this wealth of information, I asked Susan what exactly foreigners overlook when it comes to the Chinese language and she quoted a passage from ‘The Story Behind Chinese Characters’ by Lao Wan: “The shapes of Chinese characters originate from the impressions and traces of all things in nature, while their pronunciations come from their own ‘calls.’ Phonetic writing systems can be likened to ‘God’s piano,’ where each letter represents a key. For all things to express themselves, the only way is to leap onto ‘God’s piano’ and slide across each key that belongs to them, thus obtaining their pronunciations and forms to speak for themselves.”

“The philosophical depth and aesthetics of Chinese characters are often difficult to translate due to differences in context and cultural backgrounds, leading to misunderstandings. However, what I want to highlight is that even within the native-speaker community, there exists a cognitive blind spot of using them daily without truly understanding.

After all, dissemination and communication are the primary purposes of language. But the fading of philosophy and aesthetics caused by the instrumentalisation of language cannot be overlooked,” she said, while adding that this is one reason she created videos about Oracle Bone Script on her YouTube channel.

In the end, learning Chinese characters isn’t just a linguistic journey — it’s a window into an ancient way of seeing the world, one where language was inseparable from nature, emotion and the divine. What seemed at first like an impenetrable wall of strokes and symbols slowly unfolded into a landscape of thought and feeling.

Perhaps the real beauty of Hanzi lies not just in their form, but in their function: to remind us that communication is more than sound — it is art, philosophy, and the enduring echo of human imagination.