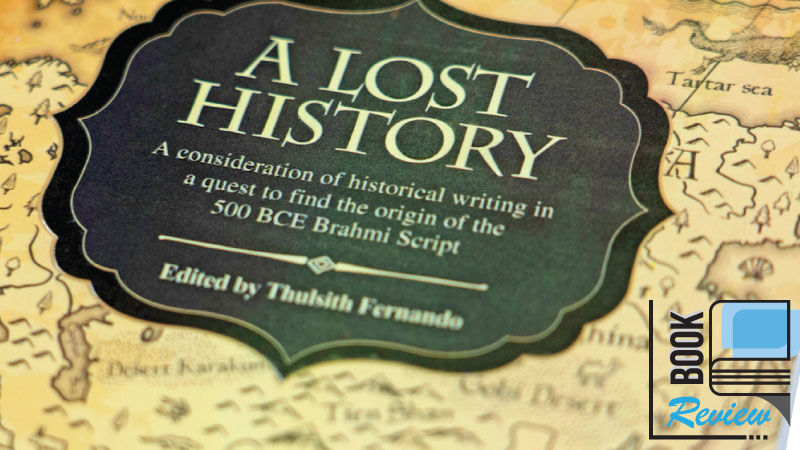

Title : A Lost History

Title : A Lost History

Author : Thulsith Fernando

Publisher : S Godage and Brothers (Pvt) Ltd.

307 pages

Received truth with regard to the Brahmi script is that it originated in the northern part of the landmass that is now known as India sometime in the 3rd Century BCE and that thanks to Emperor Asoka’s evangelical efforts, writing spread across South and Southeast Asia.

How then, Fernando asks, can one explain Brahmi script being used in Anuradhapura in the 4th Century BCE (see ‘Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the early use of Brahmi Script’ by Coningham,Allchin, Batt and Lucy) and 6th Century BCE (see ‘The prehistory and protohistory of Sri Lanka,’ by S Deraniyagala), and in Tamil Nadu in the 5th Century BCE (see ‘New evidences on scientific dates for Brahmi script as revealed from Kodimanal excavations’ by Dr. Rajanand V. P. Yatheeskumar)? That question disrupts the grand narrative about the true origin of the Brahmi script.

If it was just about a few characters on pottery shards and carbon dating, one can simply say ‘well, you don’t need an entire book to say it.’ True. Of course sometimes one single artefact is a veritable wrecking ball that can bring down an entire edifice of ‘history.’ What is fascinating about Fernando’s effort, which by the way he acknowledges is not necessary a comprehensive academic thesis (because he is not a historian), is that he has meticulously perused multiple narratives drawn from historical maritime trade accounts as well as relatively recent academic forays into the origin of script.

For example, Fernando considers the work of George Buhler on Brahmi characters. He refers to the work of R A E Coningham et al who show that ‘Buhler’s direct derivation of twenty two Brahmi characters from the Phoenician consonantal alphabet, remains by far the most convincing formulation among competing claims of Aramaic, Kharosthi and Indus Valley Civilisation derivations (which are all regarded as possible sources of the ‘North Indian’ Brahmi script).’

For example, Fernando considers the work of George Buhler on Brahmi characters. He refers to the work of R A E Coningham et al who show that ‘Buhler’s direct derivation of twenty two Brahmi characters from the Phoenician consonantal alphabet, remains by far the most convincing formulation among competing claims of Aramaic, Kharosthi and Indus Valley Civilisation derivations (which are all regarded as possible sources of the ‘North Indian’ Brahmi script).’

But then, how on earth did a Phoenician script make its way to South Asia and in particular the island we now call Sri Lanka? This is where Fernando’s account becomes utterly fascinating. He points to evidence published in 2013, of Phoenician flasks discovered in Israel, dated to around 10th century BCE, containing Cinnamon residue identified with Lanka.

He also delves into trade goods, trade routes and draws from various West Asian as well as South Asian accounts, some (but not all) dismissible as ‘legends that have no basis in real, lived history,’ but nevertheless constitute useful material to connect dots, to account for evidence of script that predates Emperor Asoka.

For example, in his chapter on the legendary island or rather the city of Tarshish, for example, Fernando brings to fore fascinating accounts as well as their interpretations in more recent times, which in the very least could fuel much needed research into pre-Vijayan trade in the region spanning from West to East Asia. Interestingly, he weaves into the narrative pertinent sections of the Ramayana and suggests that the 10th Century BCE date for the ‘legend’ as claimed by scholars such as R C Dutt, Purnalingam Pillai and C M Fernando ‘is a remarkable coincidence of many histories that converge in time.’

Now some may dismiss references to the Ramayanaya and accounts by travelers from long ago for being ‘non-academic’ (although such material is widely used in historiography deemed to be ‘academic’), but Fernando’s systematic refutation of the conservative interpretation that the Brahmi script originated in North ‘India’ deserves critical appraisal. He considers the possibility of South Indian origination as well asthe possibility of the Brahmi script originating in Lanka, being derived from a Semitic script and its use in Anuradhapura at least as far back as the 6-4th century BCE period. His conclusions are drawn from the work of recognised international archaeologists, historians and grammarians. The publication also includes valuable research citations of several Sri Lankan academic giants who are no longer with us, such as Professor Siran Deraniyagala, Dr. Malini Dias and Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere.

Fernando points out that Greek and Latin authors who wrote about writing in early India, in particular Megasthenes, the Greek advisor to KingChandragupta Maurya, oncologist, diplomat and ethnographer, who indicates that writing was not used in the Pataliputra kingdom during the early period of the Gupta rule. While Nearchos, a Greek officer in the army of Alexander the Great and Panini, a Sanskrit grammarian, who lived during the mid-1st millennium BCE, who refer to script use, but both references are considered to be Aramaic or Kharosthi rather than Brahmi script.

As Fernando suggests, it is difficult to comprehend that the entire Tripitaka and Pali Buddhist scriptures were written down in Lanka only 150 years after Lanka supposedly received Brahmi script from Emperor Asoka. New evidence has surfaced that Brahmi script was used in Lanka and Tamil Nadu, many centuries before Emperor Asoka. Fernando’s explorations run counter to the grand Indo-European civilization diffusion narratives, that imply that the island was largely uninhabited or at best was peopled by ‘tribes’ of ‘lesser’ civilisational worth.

Few, apart from some archaeologists, have wondered who was on this island before 500 BCE, what they did, what languages they spoke, whether or not they traded with peoples from lands beyond their shores, and if they had or did not have a script. Fernando’s account, by admission isnon-academic but nevertheless as painstakingly conducted as research of those with academic credentials. For those lacking the patience for research and background, I recommend a read of Part III, of the four part narrative, to comprehend the essence of his reasoning. The publication draws attention to the stark contradictions in the conventional narrative of civilisation history in Lanka, and likely to compel scholars to revisit the history of script origination in South Asia.

Considering that writing or rather its advent is a civilisational turning point, Fernando’s work on the origin of the Brahmi script calls for more rigorous academic research. South Asia’s ‘historical’ period has shifted from the 3rd to 5th century BCE, following the recent archaeological discoveries in Sri Lanka and South India. The book calls into question, the period labeled ‘prehistory’, i.e. accounts of times prior to the development of writing. We must thank Thulsith Fernando for investigating the new archaeological evidence on Brahmi script.