Sri Lanka’s local governance has deep historical roots, originating from ancient village councils known as Gam Sabhas, which managed local affairs and resolved community disputes. These indigenous systems were disrupted during British colonial rule, introducing formal Local Government structures. The Municipal Councils Ordinance of 1865 established Colombo and Kandy as the first Municipal Councils, laying the groundwork for modern local administration.

Sri Lanka’s local governance has deep historical roots, originating from ancient village councils known as Gam Sabhas, which managed local affairs and resolved community disputes. These indigenous systems were disrupted during British colonial rule, introducing formal Local Government structures. The Municipal Councils Ordinance of 1865 established Colombo and Kandy as the first Municipal Councils, laying the groundwork for modern local administration.

Post-independence in 1948, local governance mirrored national political dynamics, with major parties such as the United National Party (UNP) and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) dominating local elections. Efforts to decentralise authority, such as the establishment of District Development Councils in 1980, aimed to bring governance closer to the people. However, these initiatives often faced challenges due to political instability and civil unrest.

A significant transformation occurred with the Local Authorities Election (Amendment) Act of 2012, introducing a mixed-member proportional representation (MMPR) system. Under this system, 60 percent of local council seats are filled through first-past-the-post voting in wards, while the remaining 40 percent are allocated based on Proportional Representation. This change aimed to enhance inclusivity and fair representation across diverse communities.

The 2018 local elections, the first under the MMPR system, marked a pivotal moment as the newly formed Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) emerged as a dominant force, securing approximately 40 percent of the vote and control over 231 local authorities. This shift signalled a reconfiguration of the political landscape, setting the stage for subsequent national elections.

As the 2025 Local Government elections approach, scheduled for May 6, 2025, they will serve as a critical barometer for public sentiment, particularly in the Eastern Province, where the Muslim minority has a significant presence. These elections will test the resilience of traditional Muslim political parties and leaders, as well as gauge the influence of emerging movements such as the National People’s Power (NPP), which gained prominence following its victories in the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections.

From Ashraff to Ampara

M. A. M. Thahir – MP from ACMC

It is impossible to talk about Eastern province Muslims’ politics without talking about M.H.M. Ashraf. Mohammed Hussain Mohammed Ashraff was a transformative figure in Sri Lankan politics, particularly for the Muslim community in the Eastern Province. Born on October 23, 1948, in Sammanthurai, Ampara District. By Profession, he is a lawyer who graduated from the Colombo University and Ceylon Law College.

Ashraff’s political journey began with his involvement in the Muslim United Liberation Front (MULF), which allied with the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) in the 1977 parliamentary elections. However, after the MULF’s merger with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party in 1980, Ashraff distanced himself from the alliance. Recognising the need for a dedicated platform to represent Muslim interests, he founded the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) in 1981. Initially, a cultural organisation, the SLMC evolved into a political party by 1986, aiming to address the underrepresentation of Muslims in Sri Lankan politics.

Under Ashraff’s leadership, the SLMC gained significant political influence. He was elected to Parliament representing the Ampara District in 1989 and re-elected in 1994. Following the 1994 elections, the SLMC joined the People’s Alliance Government, and Ashraff was appointed Minister of Shipping, Ports, and Rehabilitation. His tenure was marked by efforts to uplift the Muslim community, particularly in the Eastern Province, through development projects and advocacy for minority rights.

Tragically, on September 16, 2000, Ashraff died in a helicopter crash near Aranayake, along with 14 others. The reason for the crash is still a mystery. Ashraff’s legacy endures in the Eastern Province, where he is remembered as a visionary leader who championed the rights of the Muslim community. His initiatives laid the foundation for Muslim political representation in Sri Lanka, and his influence continues to resonate in the region’s political landscape.

Political landscape in Ampara’s Muslim-majority areas

The Ampara District, situated in Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province, encompasses 20 local authorities: two Municipal Councils (Kalmunai and Akkaraipattu), one Urban Council (Ampara), and 17 Pradeshiya Sabhas (Divisional Councils). Due to a pending court case, elections for the Kalmunai Municipal Council have been suspended, leaving 19 Councils to participate in the 2025Llocal Government elections.

Among these, several councils have predominantly Muslim populations: Ninthavur, Sammanthurai, Akkaraipattu, Addalaichenai, Irakkamam, Pottuvil, and Sainthamaruthu. These areas have historically been strongholds for Muslim political parties, notably the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC).

Currently, the All Ceylon Makkal Congress (ACMC) and the National Congress are competing alongside the SLMC. Both parties were established by leaders who split from the SLMC. The National Congress in 2004 under A. L. M. Athaullah and the ACMC in 2005 under Rishad Bathiudeen.

At the 2018 Local Government elections, the ACMC secured 31 seats across the Ampara District. At the 2025 elections, the ACMC and the National Congress contested separately in various areas.

How has the change in national politics influenced?

The recent victory of the National People’s Power (NPP) in the Presidential election marked a major shift in Sri Lanka’s political landscape. For the first time in history, the NPP also won in the Ampara (Digamadulla) District, an electorate that was traditionally dominated by Muslim ethnic and regional parties. Although no Muslim candidates were elected from the district by the ruling party, the NPP later appointed a Muslim representative from Ampara district to a national list ministerial position. However, this gesture didn’t fully satisfy the expectations of the local Muslim community.

In Ampara, especially among Muslims, political loyalty often revolves around regional representation. Many believe that “the village needs a minister,” rather than just a minister from the ruling party. This highlights how regionalism and community-based identity politics are more deeply rooted in the Eastern Province than in any other part of Sri Lanka. The administrative tension between Tamil and Muslim areas further adds to the complexity. A prime example of how important local governance is: in 2019, many in Sainthamaruthu voted for Gotabaya Rajapaksa because he promised to create a separate Pradeshiya Sabha for their town.

An SLMC meeting at Nintavur

During our fieldwork before the Local Government election in Ninthavur, several residents expressed a split political approach: they might vote for national parties during the Presidential or parliamentary elections, but prefer ethnic or community-based parties for local elections. As one person said, “No matter how bad the situation is in the country, Local Government is close to us. We should choose people we know and trust.”

There is growing discontent with the current leadership of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC). Many said they had no trust in its leader, Rauff Hakeem, and accused the party of losing its way after the death of founder M.H.M. Ashraff. Yet, some said they would still vote for the SLMC, not because of its present leadership, but because the party, to them, still symbolised Muslim identity and past development initiatives started by Ashraff.

People also expressed anger at former and current Muslim MPS for supporting the controversial Twentieth Amendment and remaining silent during the forced cremation of Muslim Covid-19 victims. Many believe those MPS prioritised personal gain over community needs.

As for the NPP, despite winning nationally, it faces distrust at the local level in places such as Ninthavur. Many of its local candidates are seen as former SLMC members who switched allegiances, leading people to doubt their motives. Longtime leftist activists in the area, some aligned with the original JVP movement since the 1980s, told us they felt excluded and unacknowledged by the current NPP leadership. This alienation has reduced the grassroots enthusiasm for the party.

Moreover, the entrenched power of political families, money, and party loyalty in the region makes it difficult for a new party such as the NPP to break through. Some voters also feel the NPP has failed to deliver on its promises, such as repealing the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and not appointing any Muslim cabinet minister, and thus question whether the party can be trusted in local elections.

In short, while national politics have changed, local loyalties, historical grievances, and the demand for visible, community-based leadership continue to dominate the political choices of Muslims in Ampara.

What is the status of the Muslim Congress?

The Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC), once a dominant force in Muslim politics, is currently facing internal challenges and declining public trust. Founded by M.H.M. Ashraff to represent Muslim interests, the party has experienced significant internal divisions over the years. One notable figure, Hassan Ali, a founding member and former General Secretary, expressed his disillusionment with the party’s current direction.

When entering Alli’s house, on the right side, there were pictures and banners of leaders, including Ashraf, and the history of the Muslim Congress written on them. On the other side, a large picture of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake was pasted. This scene surprised us. While talking with Ali, he criticised the SLMC leadership for deviating from its original mission and failing to serve the community effectively.

The SLMC’s internal conflicts have led to splinter groups, such as the All Ceylon Muslim Congress (ACMC) and the National Congress, further fragmenting the Muslim political landscape. These divisions have weakened the party’s influence and raised questions about its ability to represent Muslim interests effectively.

Whose side are the women on?

Women play a crucial role in Sri Lankan elections, often determining the outcome through their votes. In the Eastern Province, particularly in the Ampara district, women’s support is highly sought after by political candidates. Some politicians have resorted to very cunning methods to get women’s votes. For instance, M.L.A.M. Hizbullah, a prominent SLMC figure, is known for his direct engagement with women during His canvassing. ‘Everyone stops at the gate. Maximum is going inside to the hall. But Hizbullah, without stopping at the gate, directly walks to the kitchen and serves food from the pot by himself and eats,” is very popular.

Despite the rise of social media and increased political awareness, many women in rural areas continue to follow traditional voting patterns, often influenced by family and community ties. While some women express support for national parties during canvassing visits, their actual voting behaviour remains uncertain until election results are announced.

Women’s representation in politics remains low. The traditional major political parties did not allocate any percentage of nominations to women, and with the social and cultural barriers, Muslims cannot actively participate in politics in Muslim areas in the Eastern province. However, we observe that they went to Local Government authorities through the quota and do politics very efficiently today, amidst the challenges.

2025 Local Government election results: shifts in power and regional dynamics

The 2025 Local Government Election marked a significant shift in Sri Lanka’s political landscape. The National People’s Power (NPP) emerged as the dominant party on a national scale, securing 43.26 percent of the total vote and winning 3,927 seats across 266 local councils. This included 23 Municipal Councils and 217 Pradeshiya Sabhas. However, despite its numerical strength, the NPP faced considerable obstacles in forming outright administrations in key councils. For example, in the Colombo Municipal Council, the country’s largest and most symbolic council, the NPP secured 48 out of 117 seats but still fell short of a clear majority. This reflected a broader trend of coalition dynamics under the mixed-member proportional representation system.

Ampara District: A microcosm of ethnic and political trends

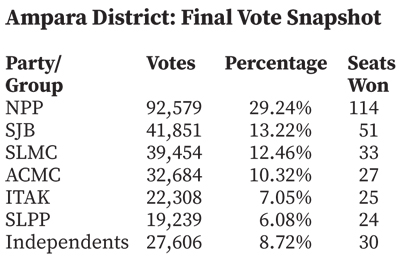

Zooming into the Ampara District, a region marked by its ethnic diversity and complex political history, the NPP once again emerged as the largest single party, winning 29.24 percent of the vote (92,579 votes) and securing 114 seats.

However, the party’s performance here lagged significantly behind its national average. While the NPP had previously shown strength in parliamentary elections, particularly after its 2024 “supermajority” win, the local polls in Ampara revealed underlying discontent, especially in Muslim and Tamil-majority areas. Voter turnout in these communities was relatively lower, and a noticeable segment of the electorate shifted their support to regional and identity-based parties.

Ethnic parties retain ground in the East

Ethnic-based political parties retained a strong grip in Ampara. The Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi (ITAK) secured 7.05 percent of the vote (22,308 votes) and won 25 seats, consolidating its hold in Tamil-dominated localities.

The Muslim community largely continued to back their traditional parties: the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) won 12.46 percent (39,454 votes) and 33 seats, while the All Ceylon Muslim Congress (ACMC) gained 10.32 percent (32,684 votes) and 27 seats. Combined, these Muslim parties captured over 22 percent of the vote, reflecting their enduring influence among Muslim voters despite the national rise of the NPP.

Independentc and local power shifts

Perhaps, most notably, independent candidates led by former MPS made significant inroads. In the Pottuvil Pradeshiya Sabha and Akkarappattu Municipal Council, Independents led by ex-MPS Musharraf and A. L. M. Athaullah emerged victorious. Their wins were seen as a direct challenge to the hegemony of traditional political parties and a signal of localised dissatisfaction with party politics. These victories not only disrupted the expected balance of power but also underscored the importance of personal reputation and grassroots campaigning in local elections.

Perhaps, most notably, independent candidates led by former MPS made significant inroads. In the Pottuvil Pradeshiya Sabha and Akkarappattu Municipal Council, Independents led by ex-MPS Musharraf and A. L. M. Athaullah emerged victorious. Their wins were seen as a direct challenge to the hegemony of traditional political parties and a signal of localised dissatisfaction with party politics. These victories not only disrupted the expected balance of power but also underscored the importance of personal reputation and grassroots campaigning in local elections.

Key takeaways

The results from the Ampara District offer several key insights. Firstly, ethnic voting patterns remain strong, with ITAK and Muslim parties successfully capitalising on identity politics. Secondly, the NPP’s struggles in minority-heavy districts such as Ampara reveal a persistent rural-urban and ethnic disconnect in their outreach strategy. Finally, the victories of independent candidates point to a growing dissatisfaction with mainstream political platforms and a shift toward more localised, personality-based politics.

As Sri Lanka navigates a politically volatile environment, the 2025 Local Government election results from the Eastern and Northern provinces serve as a reminder that national momentum does not always translate to local success, especially in a region where community identity and grassroots presence still carry significant weight.