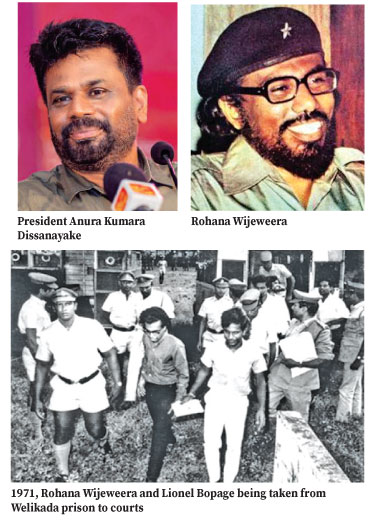

On May 14, 1965, a group of revolutionary-minded youth, led by comrade Rohana Wijeweera, founded the ‘Movement’ which would later become the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). Emerging amidst growing disillusionment with the traditional left, the JVP was influenced by global liberation movements, including the Cuban Revolution and Maoist insurgencies in Asia. It represented a new political current in Sri Lanka – an alternative to the declining credibility of the established Leftist parties.

On May 14, 1965, a group of revolutionary-minded youth, led by comrade Rohana Wijeweera, founded the ‘Movement’ which would later become the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). Emerging amidst growing disillusionment with the traditional left, the JVP was influenced by global liberation movements, including the Cuban Revolution and Maoist insurgencies in Asia. It represented a new political current in Sri Lanka – an alternative to the declining credibility of the established Leftist parties.

The roots of the Left

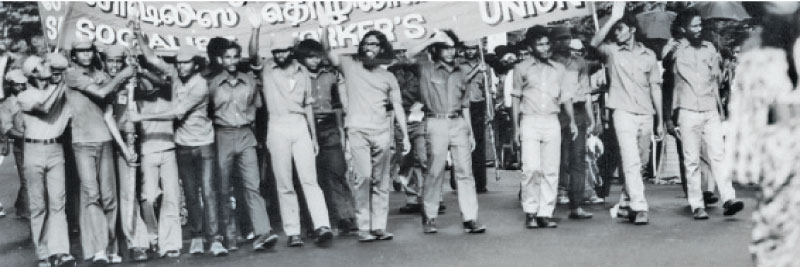

Sri Lanka’s Leftist politics took shape in the 1930s, grounded in anti-colonial sentiment and growing class consciousness among workers. Trade unions played a central role in mobilising resistance against colonial economic structures, with parties such as the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) advocating a mix of nationalism and socialism. However, the LSSP’s eventual integration into coalition politics, particularly with the SLFP in 1964, signalled the beginning of its ideological dilution and alienation from radical grassroots movements.

Sri Lanka’s Leftist politics took shape in the 1930s, grounded in anti-colonial sentiment and growing class consciousness among workers. Trade unions played a central role in mobilising resistance against colonial economic structures, with parties such as the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) advocating a mix of nationalism and socialism. However, the LSSP’s eventual integration into coalition politics, particularly with the SLFP in 1964, signalled the beginning of its ideological dilution and alienation from radical grassroots movements.

The rise of the new Left

By the 1960s, the Cold War shaped the global political climate, with the U.S. supporting authoritarian regimes to suppress socialist movements. In Sri Lanka, pro-Western elites pushed anti-democratic policies, including suspending elections. Amid this repression and growing fragmentation within the Communist Party of Ceylon, comrade Wijeweera’s faction formed a covert revolutionary group – the ‘Movement’ – seeking to challenge the Capitalist State.

This ‘Movement’ rejected both the pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese lines of the traditional Left, developing its own ideological path, dubbed the “Lanka Line.” It prioritised economic self-sufficiency, agricultural industrialisation, and a break from dependence on Western powers. Unlike the LSSP, which collaborated with ruling coalitions, the ‘Movement’ directly confronted the systemic inequalities embedded in class, ethnicity, and caste.

Legacy of the traditional Left

The traditional Left’s failure lay in its inconsistent commitment to inclusivity and democratic participation. Since 1956, it increasingly aligned with Sinhala nationalism, supporting policies that marginalised Tamil and Muslim communities, including the 1972 Constitution’s endorsement of Sinhala as the official language and Buddhism as the State religion.

Tied to either Soviet or Chinese blocs, traditional Left parties often pursued ideological loyalties over pragmatic solutions. While many cadres were sincere, their dependency on external support diluted the independence and credibility of the traditional Left Movement.

Conflict with the establishment

The ‘Movement’, initially operating underground, began to build a mass base among the semi-proletarian and lower-middle classes. By 1970, under increasing State surveillance, it transitioned into a political force and formally adopted the name Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). Comrade Wijeweera was arrested shortly before the United Front’s electoral victory, but was later released, sparking a surge in JVP’s popularity. This rise in popularity alarmed the Government. Despite the JVP’s focus on mobilisation and public education, the State designated it as a subversive threat to be eliminated.

The Government used the death of a police officer in March 1971 during a Maoist Youth Front-led demonstration in front of the US Embassy in Colombo as a pretext to declare a State of Emergency. A brutal crackdown ensued, culminating in the April 1971 insurrection and its violent suppression.

JVP’s evolving identity

Though initially inspired by Maoist thought, the JVP gradually evolved beyond rigid ideological frameworks. It distinguished itself through discipline, voluntary sacrifice, and rejection of consumerist political culture. Its cadre system fostered a sense of community, dedication, and purpose. Environmental sustainability, centralised democracy, and rejection of opportunistic politics became core principles. Despite State repression—including two mass exterminations—the JVP survived, in part due to the enormous dedication of its rank and file.

By 1977, it began rebuilding its political presence. In the 1981 District Development Council elections, 13 JVP candidates were elected but denied basic resources by the ruling UNP. Yet, they donated their earnings to the party, reinforcing its culture of collective sacrifice, which continues as a tradition to this day.

Over time, the JVP transitioned from insurrectionary politics to Parliamentary engagement. Since 2019, it has contested elections under the broader National People’s Power (NPP) coalition. In 2024, this transformation culminated with the NPP winning a supermajority in Parliament, and the largest island-wide vote at the Local Council elections held last week.

This victory represents a historic shift in Sri Lankan politics. The NPP-led Government is now tasked with addressing structural inequalities, democratic erosion, and economic mismanagement.

Its success will depend on its ability to deliver inclusive governance, resist authoritarian impulses, and build transparent institutions.

Looking ahead

The JVP’s journey—from an underground revolutionary group to a governing party—has reshaped the political landscape. In contrast to traditional parties that preserved elite privileges, the JVP/NPP has positioned itself as a voice for the marginalised. However, realising this vision requires not just State power, but deep, participatory engagement with civil society and grassroots movements.

To ensure meaningful change, the new leadership must break from the cycles of repression, corruption, and exclusion. Social transformation in Sri Lanka will ultimately hinge on democratic reforms, equitable development, and sustained public participation.

Rohana Wijeweera at a May Day rally