Blending memory and imagination, Elizabeth Graver’s award-winning novel draws on Sephardic Jewish culture, family archives, and the power of song to tell a story that spans continents and generations.

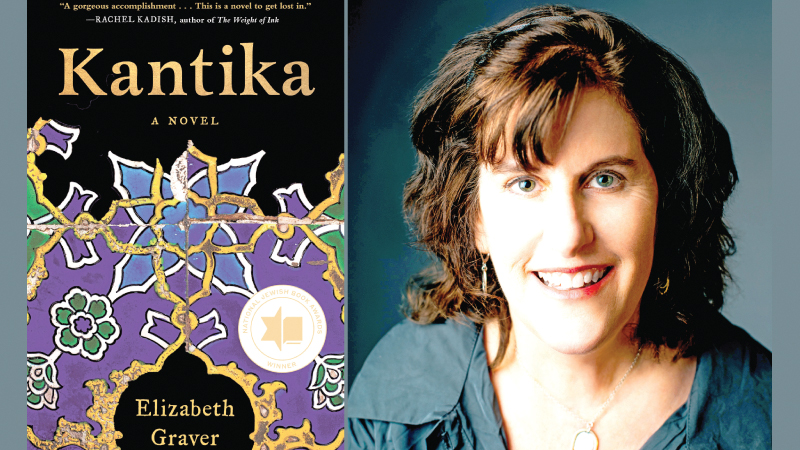

“Iwas just twenty-one, in 1985, when I first started recording my grandmother’s stories,” confides Elizabeth Graver, now the celebrated author of Kantika, her luminous fifth novel that has swept up the Massachusetts Book Award for Fiction, the Edward Lewis Wallant Award, the National Jewish Book Award for Sephardic Culture, and the Julia Ward Howe Prize.

“Iwas just twenty-one, in 1985, when I first started recording my grandmother’s stories,” confides Elizabeth Graver, now the celebrated author of Kantika, her luminous fifth novel that has swept up the Massachusetts Book Award for Fiction, the Edward Lewis Wallant Award, the National Jewish Book Award for Sephardic Culture, and the Julia Ward Howe Prize.

Hailed by The New York Times, National Public Radio, and Libby as a top book of 2023, Kantika (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt & Co, 2023) is a family saga that spans cultures and continents while exploring themes of cultural displacement, diaspora, and anti-Semitism. A German translation has come out, with a Turkish one to follow in 2025.

In a conversation with the Sunday Observer, Graver shared the moment when she felt called to turn her grandmother Rebecca’s deeply personal story into a novel. Born into a Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jewish family in Turkey, Rebeca née Baruch Cohen carried fragments of multiple languages, religious traditions, and diasporic memories across multiple migrations. Kantika borrows its title from the Ladino word for “song,” a concept Graver found central to the Sephardic experience of displacement and resilience.

Growing awareness

For a long time, she hesitated to write the novel. “I didn’t know enough,” Graver admits. “I didn’t speak Ladino, also called Judeo-Spanish—a language that formed in diaspora after the Sephardic Jews were expelled from Spain in the 1400s—and the culture my grandmother was from felt quite distant, even as I was drawn to it.” Only in 2014 did she begin in earnest. Part of that timing, she said, was her growing awareness of the current refugee crisis, rising antisemitism, and her desire to give voice to people whose histories had gone untold for too long. “I teach university students from all over the world, and their stories are rich, sometimes painful and important”, she says. “Their stories, the larger political climate, the Trump era, everything started to align. Also, I wanted my uncles and mother, the generation aging above me, to get to share their stories and witness the book. It felt suddenly urgent.”

Kantika is a linguistically rich novel. Readers are given a taste of a multilingual world where Ladino, Hebrew, French, and English are woven together, each language revealing a piece of Sephardic culture’s travels across centuries and continents.

“Ladino is endangered,” Graver points out. “Many readers, sometimes even in Jewish communities, haven’t heard of it. I wanted to weave in Ladino songs and phrases so people could encounter the richness.” She confronted a delicate balancing act: how much to translate, and how much to leave in its original form. “Fiction can be a little alienating in a good way,” she suggests. “It can make you curious. You might not know every word, but you feel the musicality. The reader becomes almost like an immigrant into the world of the story, trying to understand.”

Critics have described Kantika itself as a “song”, both a lament for lost worlds and a love song. When asked to elaborate on the musicality of the novel and its role in shaping the narrative, Graver had an interesting answer. “Rebecca, the protagonist, loves to sing. Songs are portable, and they’re passed from generation to generation. When you’re forced to leave a place, you have to abandon your home, your furniture, your garden, but songs can come with you.. Drawing on Sephardic lullabies, liturgical pieces, and street songs, Kantika exhibits how intangible cultural heritage survives even when communities scatter.”

Though Kantika is proudly Sephardic, Graver grew up in a secular Jewish household and mostly learned about two very different sets of Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions from her two sets of grandparents. “My parents’ marriage was almost considered a ‘mixed marriage’ by their families. . My mother’s side spoke Ladino, my father’s side spoke Yiddish. One side ate baklava, the other ate gefilte fish.”

The dominant narrative of Jewish migration in American literature has been Ashkenazi: families fleeing Russian pogroms and World War II, settling in the Lower East Side, speaking Yiddish. By contrast, the Sephardic story, rooted in the expulsion from Spain in 1492, subsequent resettlement throughout the Ottoman Empire and beyond, and multiple waves of displacement, remains less known. Kantika meets that gap head-on, rendering the foods, melodies, and hybrid traditions of Sephardic life.

Kantika spans multiple geographies—Istanbul, Cuba, Barcelona, New York—yet it never loses its emotional intimacy. When I asked Graver how she kept close to the heart of the story while moving to vastly different settings, she said the novel required a lot of research, extensive archival work, and travel, and that she felt she was almost on a guided tour spanning past and present. “I’d only visited Turkey before—and of course, New York. Cuba and Spain were brand new to me. I interviewed people and walked the streets where my grandmother had lived. In Barcelona, I placed a pebble on my great-grandfather’s grave, which is a Jewish custom. But when it came to the actual writing, I had to embody the characters in a different way. It was me trying to be Rebecca when she was 22, when she’d just arrived in Barcelona.

And then again thinking about what she would see and notice in Cuba, where she arrived for an arranged marriage, having left her tiny sons from her first marriage behind in Spain. I use a wide lens when I’m taking everything in, but a narrow lens when I’m imagining the inner lives of the people. The novel can be such an intimate form, but Kantika is also about big history—the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II. That’s what partly took me so long. I had to learn the facts and then get rid of a lot, draw really close”.

Among other things, I was interested to know more about how Graver struck a balance between historical accuracy and creative liberties. “I’m a novelist. One of my favourite things is dreaming my way inside people’s heads, so that part isn’t hard for me”, Graver acknowledged with a laugh. “But what surprised me was that I thought I would only follow Rebecca, but along the way, I got interested in Alberto’s character, who was inspired by my great-grandfather, a man I never met, even my mother never met.

Early on, I did toy with the idea of nonfiction, but ultimately, I preferred the freedom fiction offers, particularly in exploring private moments for which no documentation exists. That said, I strove for historical accuracy in dates, locations, significant events, and cultural details. Fiction lets me bridge the gaps between the factual fragments and the emotional truths of my characters. I couldn’t research what Alberto was thinking as he walked across the city, but I could dream it up”.

Adjustment, strengths and limitations

Moving to her protagonist, I asked Graver how she shaped Rebecca, who is “strong, resourceful, deeply connected to her roots, yet constantly reinventing herself”, and whether that strength was present from the start or emerged over time. “The hardest part of the book for me, which might sound surprising, was the portion set in the United States. You’d think it would be easier, I live here, I know this world—but I had far more anxiety: Am I getting it right? Is this my story to tell? The book’s last third didn’t work in the first rendition, and I threw it away. It was very on the surface.

My mother—she’s 88 now and a retired English professor, and we’re close—read that earlier draft and said, if you want to write about my mother, Rebecca, you have to write about her relationship with Luna. This was at the heart of Rebecca’s adjustment, strengths, and limitations. I was nervous. My Aunt Luna, who had cerebral palsy and was my grandmother’s stepdaughter, died before I began the book. I’d been close to her, and I admired her enormously, but writing about disability in the 1930s and 40s felt daunting. In real life, my Aunt Luna wrote newspaper articles in her retirement, and she recorded some childhood memories as well.

It was vital to me to give the character inspired by her a strong voice and point of view. Once I rewrote those chapters around Rebecca and Luna, Rebecca truly got tested. She arrives in the U.S. unaware of her stepchild’s health problems, while still separated from her biological children.

The bond is complicated: Luna is smart, angry and seeking connection; Rebecca, too, has anger and love. They negotiate with each other constantly. It’s more nuanced than Rebecca being just a strong, resourceful woman; sometimes she says troubling things, sometimes Luna exposes her hypocrisies. That difficulty, once I embraced it, felt the most alive, and I hope I did it justice.”

“In real life,” Graver went on, “they also had a quite complicated relationship. In the novel, I explored how Rebecca is always working with surfaces; she’s a dressmaker, beautiful, able to turn herself from a Turkish Jewish woman into passing as a French woman. She loves to act, to be on stage. Luna can’t shape-shift; her body is disabled, and in a prejudiced culture, people don’t always see past that. As a child, I remember we’d go out to dinner, and someone would ask me what Luna wanted to eat. I’d say, ask her—she can speak. That tension interested me. There’s a moment in the novel when Rebecca tells Luna, Let everyone see what you’re like underneath, and Luna thinks, You never pass a window without admiring your reflection. Luna sees Rebecca’s hypocrisies. None of the characters are perfect. I’m interested in human frailty and complexity, and I love them all, even when they’re flawed.” To be continued next week