In recent years, a quiet but powerful shift has begun in many Sinhala-speaking homes across Sri Lanka. More and more parents are choosing to raise their young children, especially those under age five, entirely in English, believing it will give them an edge in education and future careers.

In recent years, a quiet but powerful shift has begun in many Sinhala-speaking homes across Sri Lanka. More and more parents are choosing to raise their young children, especially those under age five, entirely in English, believing it will give them an edge in education and future careers.

But a new research study has raised an important red flag: this language shift may be creating unintended consequences in children’s emotional development, family relationships, and connection to their culture.

Conducted across urban Sinhala-speaking families, the study found that while parents value English for upward mobility, many children are losing touch with their Sinhala-speaking grandparents, traditional stories, and even their own ability to express deep emotions in their native language.

What’s Happening in Our Homes?

The trend is growing, especially among educated, urban families. Parents who struggled to learn English themselves now want to make it their child’s first language, from birth. They speak English at home, send their toddlers to English-medium playgroups, and often avoid using Sinhala altogether.

The reason? English is seen as the ticket to good schools, global jobs, and social status. But while children may become fluent in English, many are missing out on something deeper: meaningful conversations with Sinhala-speaking grandparents, cultural expressions, and even the emotional warmth carried in a mother tongue.

In some homes today, children are growing up without understanding simple folk tales or knowing how to respond when a relative affectionately says, “Mage duwa” or “Mage putha” (my daughter/son). The warm familiarity of Sinhala expressions is being replaced with textbook-style English. For young children, this shift can lead to confusion, a sense of emotional distance from family members, and even early struggles with their sense of identity.

What We’re Losing: Stories, Feelings, and Belonging

Language is not just about words, it’s how children build emotional bonds, understand others, and feel at home in the world. In Sinhala-speaking families, storytelling has long played a special role. Grandparents once spoke of “Handa Mama” (Uncle Moon), trees that whisper, or animals that teach kindness. These weren’t just stories; they were lessons in empathy, nature, and being human.

But when a child grows up speaking only English, these stories often disappear. Grandparents struggle to connect. Jokes, lullabies, or even expressions of love get “lost in translation.” One researcher called it “shared language erosion”when families stop understanding each other, even while sitting in the same room.

This loss doesn’t just affect relationships. Experts say that emotional intelligence and empathy grow best when children feel understood and connected. If a child can’t fully share their feelingsor understand the feelings of others, in their mother tongue, they may feel isolated even within their own family.

A recent research study conducted as part of this investigation compared the behavioral patterns of children from Sinhala-speaking households with those from new English-speaking families, where one or both parents choose to raise the child in English, even though it is not their home language. The findings revealed noticeable differences: children who spoke Sinhala at home but attended bilingual or English-medium playgroups adapted well, showing strong skills in empathy, teamwork, and sharing. In contrast, children raised primarily in English within such families, often with limited exposure to Sinhala or cultural grounding, tended to struggle with emotional expression, cooperative play, and forming social bonds. While English-medium education is gaining popularity among modern urban parents, the absence of a stable home language and cultural context may hinder critical aspects of a child’s social and emotional development.

Are Our Preschools Ready for This Shift?

While many Sri Lankan parents are eager to give their children an “English start,” the early education system isn’t keeping pace. A recent analysis of preschool job advertisements across Sri Lanka reveals a worrying truth: there’s no consistent standard for playgroup teachers who handle children aged 3 to 5.

Most preschools require only a basic diploma or a Montessori certificate, often without a regulated national framework. In some ads, fluency in English and computer skills are highlighted more than formal training in early childhood education. In contrast, countries like the UK and Australia demand a bachelor’s degree and national certification for those teaching the youngest children.

This lack of regulation means that even if parents want high-quality English-medium education, many children are being taught by underqualified teachers during the most critical years of their development. Without trained professionals who understand both child psychology and bilingual development, we risk prioritising English over quality, and children may suffer for it.

So What Can Parents Do?

The good news is that parents don’t have to choose between Sinhala and English. Children are fully capable of becoming bilingual, especially when they’re exposed to both languages in a loving, consistent environment. In fact, research shows that early bilingualism can improve memory, problem-solving, and even empathy.

The key is balance. Speak Sinhala at home, especially with grandparents. Let your child hear bedtime stories in your own voice, with the warmth of familiar words. Encourage English through books, songs, or school, but don’t let it replace your child’s emotional and cultural roots.

And when choosing a preschool, don’t just ask about the language of instruction. Ask about the teachers’ qualifications.

Are they trained in early childhood development? Do they understand how language affects emotion, behaviour, and identity? Your child deserves more than just good English,they deserve good education.

A Language Choice That Shapes a Lifetime

Teaching your child English is a gift, but forgetting Sinhala could be a loss that’s harder to repair. Language is more than a skill for exams; it’s how children feel love, share stories, understand their culture, and know who they are.

This is not a call to reject English. It’s a reminder not to lose what makes us Sri Lankan in the process. Strong roots help children grow tall. By nurturing both Sinhala and English, we give our children the best of both worlds: confidence in the global arena, and a heart that still understands home.

Before we rush to raise “English-speaking kids,” let’s ask ourselves: Will they still know that Handa Mama is offering kiri and peni?

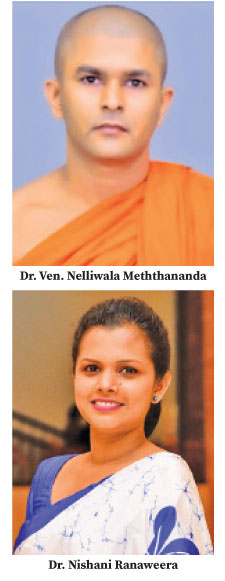

Dr. Ven. Nelliwala Meththananda

Senior Lecturer

Department of Philosophy and Psychology,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura

Dr. Nishani Ranaweera

Senior Lecturer

Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura