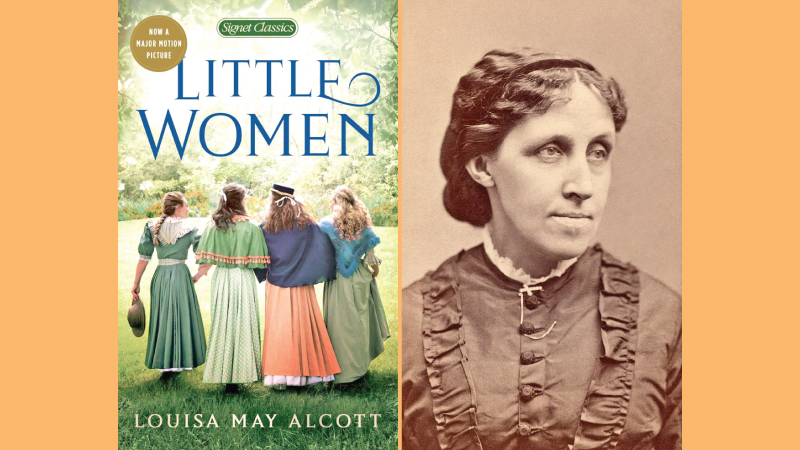

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women remains one of the most cherished novels in English-language literature, more than 150 years after it first appeared. Published in two volumes between 1868 and 1869, it tells the story of the March sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—growing up in Civil War-era New England. But it does much more than narrate the events of their youth; it explores ambition, loss, sisterhood, creativity, and the quiet strength of domestic life with an honesty that continues to resonate across generations and continents.

The novel begins with a moment many readers know by heart. “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbles Jo, setting the tone for a story both humble and hopeful. From that first page, Alcott invites us into the March home, it is not one of wealth or grandeur, but of warmth, laughter, hardship, and love.

Charming

The universal charm of Little Women lies in its truthfulness. Alcott wrote from life. Jo March, the story’s fiery heart, is a stand-in for Alcott herself—a woman who wanted more than marriage and housekeeping, who longed to write, to earn her own living, to be free. Readers see themselves in Jo’s hunger for purpose, her frustration with the world’s limits, and her fierce devotion to her family. But the novel never places one dream above another. Meg, who chooses domestic life; Beth, who embraces quiet kindness; Amy, who seeks beauty and status through art—each sister walks a different path, and none is judged. This balance, this celebration of variety in womanhood, gives the novel its timeless appeal.

Though written in the 19th century, the novel’s emotional terrain is startlingly modern. The sisters face ordinary challenges—a burned dress, a petty quarrel, a schoolboy’s teasing—but also heavier ones: sickness, poverty, loss, regret. The death of Beth, quiet and inevitable, is still one of literature’s most affecting scenes. Alcott doesn’t romanticise it. She lets us sit in the ache of it. “I’m not afraid, but it seems as if I should be homesick for you even in heaven,” Beth tells Jo. Few readers forget those words.

What makes Little Women so loved by readers is not just what happens to the March girls, but how Alcott tells it. The prose is clear and grounded, never inflated. It doesn’t hide behind literary tricks or embellishment. Instead, it speaks plainly and earnestly, as if Alcott is sitting beside you, telling the truth. The tone is affectionate but unsentimental. Alcott allows room for flaws, contradictions, and hard decisions. She understands that goodness isn’t easy, that growing up means letting go of some things you love, and that the right choices are often quiet ones.

In terms of literary influence, Little Women has been nothing short of foundational. It opened the door for stories centred on ordinary girls’ lives—without princes or gothic mystery—yet with depth and value. Jo March, with ink on her fingers and rejection letters in her drawer, became a figure who inspired writers from Sylvia Plath to Simone de Beauvoir. The novel laid groundwork for women’s fiction, domestic realism, and the idea that family stories, told honestly, are literature.

Dream differently

Alcott’s refusal to marry Jo off for convenience or cliché also marked a quiet rebellion. When Jo rejects Laurie, the charming boy next door, many readers were outraged—then and now. But Alcott stood firm. She wasn’t writing a fairy tale. She wanted Jo to choose her own life, not have it handed to her. In doing so, she gave young readers, especially girls, permission to dream differently.

The universality of Little Women stems from its human core. It’s about making sense of who you are while growing up alongside others. It’s about facing change without losing yourself. It’s about love—not just romantic, but the kind that grows over time, between siblings, friends, parents, and self.

Even now, in a world unrecognisable from the one Alcott knew, readers find themselves in those pages. Whether they see their ambition in Jo, their calm in Beth, their grace in Amy, or their steadiness in Meg, there is room in Little Women for everyone. It doesn’t offer spectacle. It offers sincerity.

And maybe that’s why it’s lasted, especially because it never tries to impress. It just speaks from the heart.