Some films age like wine. My Fair Lady, directed by George Cukor and released in 1964, is one such rare vintage. Based on George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion, this Technicolour musical has become more than just a period piece. It’s a charming, layered, and surprisingly relevant story about class, transformation, identity, and self-worth. More than sixty years later, it still holds audiences in its spell with its unforgettable songs, witty dialogue, exquisite costumes, and, above all, its unique heart.

At its core, My Fair Lady follows Eliza Doolittle, a poor flower seller with a strong Cockney accent, who is picked by the arrogant phonetics professor Henry Higgins as part of a social experiment. Higgins bets that he can pass her off as a refined duchess simply by training her to speak “proper English.” What begins as a linguistic makeover turns into something deeper, an exploration of identity, dignity, and the hidden cost of reinvention.

Eliza, played with elegance and spark by Audrey Hepburn, begins the film as rough and spirited. Higgins, portrayed by Rex Harrison, is brilliant, sharp-tongued, and insufferably proud. Their interactions are electric, sometimes hilarious, sometimes painful, and always revealing. As Eliza learns to speak like a lady, she slowly realises she’s also learning to think for herself, challenging Higgins’ dismissive worldview.

Why it’s still loved

There’s something magical about this film that goes beyond its surface glamour. It’s in the details especially in its rich sets, the meticulous costumes, the elegant direction. But more than that, it’s the characters that stay with you. Eliza is not just a woman being “improved”; she’s someone discovering her own worth. The moment she realises she doesn’t need Higgins, that she is “a lady” because she chooses to be one, remains one of the most quietly powerful scenes in musical cinema.

The music, composed by Frederick Loewe with lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, is iconic. Songs like Wouldn’t It Be Loverly, I Could Have Danced All Night, On the Street Where You Live, and The Rain in Spain still linger in memory. These songs carry emotional weight while pushing the story forward instead of simply decorating it.

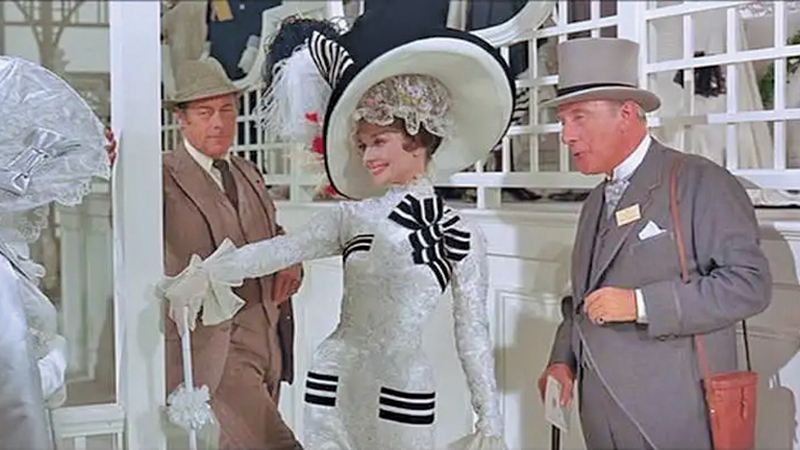

Cukor’s direction is elegant without being heavy-handed. The film is long, as I remember it is almost three hours, but never drags. Every scene is crafted with care. The lavish set pieces, especially the Ascot races and the Embassy Ball, are like living paintings. Cecil Beaton’s costume design won the Oscar for a reason as his work gives the film much of its visual identity. But it never overshadows the emotional threads running through the story.

Cukor’s direction is elegant without being heavy-handed. The film is long, as I remember it is almost three hours, but never drags. Every scene is crafted with care. The lavish set pieces, especially the Ascot races and the Embassy Ball, are like living paintings. Cecil Beaton’s costume design won the Oscar for a reason as his work gives the film much of its visual identity. But it never overshadows the emotional threads running through the story.

Even in its grandeur, My Fair Lady doesn’t forget the small, human details: Eliza’s exhausted frustration as she repeats phonetic drills, the quiet pride in her face when she first speaks “properly,” and the wounded dignity she carries when she walks away from Higgins. These moments make the film breathe.

Unlike many transformation stories, My Fair Lady avoids becoming a shallow makeover fantasy. Eliza’s journey is not just physical, it’s truly emotional, intellectual, and moral. She doesn’t just change to please someone else. She grows, reflects, and ultimately chooses herself.

Henry Higgins, for all his brilliance, never truly changes. And this is where the film is especially bold. In many romantic musicals, the hero softens and the couple comes together in mutual growth. But here, Eliza’s strength lies in the fact that she evolves while Higgins remains largely static. Their relationship remains complicated, more rooted in mutual respect than romance. The film resists a conventional fairytale ending—and that’s part of its strength.

Remarkable complexity

This complexity is what makes the film stand out. It’s not just about flowers and ball gowns. It’s about power dynamics, self-respect, and what it means to be seen for who you really are.

In today’s world of social pressure, class differences, and self-branding, My Fair Lady feels oddly current. Eliza’s story speaks to anyone who’s ever felt looked down on for the way they speak, dress, or come across. It raises questions about who gets to decide what’s “correct,” what makes someone “refined,” and why those things matter.

It also reminds us that change can be beautiful, but it should be on our own terms. The most touching lesson of the film is this: you don’t need to become someone else to be worthy of respect. Eliza doesn’t need Higgins to validate her. Her self-worth isn’t granted by a professor, it’s claimed by herself.

My Fair Lady is not just a musical. It’s a story about dignity wrapped in elegance, with moments of humour, heartbreak, and quiet strength. Audrey Hepburn shines in a role that demanded far more than glamour, and Rex Harrison’s Higgins is both maddening and magnetic.

Even with its 1960s gender politics and flaws, the film manages to feel rich, layered, and strangely modern. Its magic isn’t just in the songs or the sets, but in the way it asks us to look closer at language, power, pride, and the real meaning of becoming a “lady.”

It’s a fair lady of cinema indeed. And a timeless one.