Geotab, a world leader in connected transportation solutions, analysed 10,000 Electric Vehicles (EV) and found that their batteries can last over 20 years.

By performing simple maintenance tasks, drivers can effectively extend the life of their EV batteries, research shows.

Geotab said that EV battery performance has improved significantly over the past five years.

Researchers found that EV batteries degraded at an average rate of 1.8 percent annually in 2024, compared with 2.3 percent in 2019.

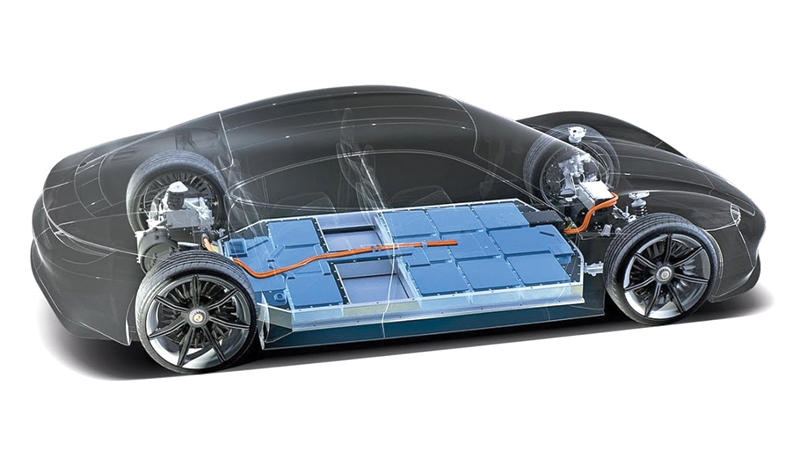

The company’s EV battery analysis revealed that most modern EV batteries last 15 to 20 years under moderate conditions. However, Level 2 charging helps preserve battery life, as frequent DC fast charging accelerates degradation, especially in extremely hot climates (such as Sri Lanka and India).

Geotab recommended that drivers maintain a charge between 20 percent and 80 percent, limit fast charging, and minimise extreme temperature exposure to extend EV battery life.

This new data from Geotab stands out because it supports the transition to clean energy driving. It helps ease anxiety among new EV owners and provides practical tips for maximising your EV investment by making the batteries last longer.

High vehicle use does not negatively impact EV battery life, so you can reduce the total cost of ownership by increasing road hours,” said a Geotab blog post. “In fact, keeping EVs in regular operation can promote optimal battery health by maintaining steady charge cycles and preventing prolonged inactivity, which can lead to reduced efficiency.”

Owning an EV is one of the best ways to limit air pollution and save money on gas and maintenance costs.

You can save even more on EV ownership by charging at home with solar panels instead of paying for public charging stations. As the used EV market rapidly expands worldwide, it might make sense to sell your EV while the battery is still in great condition.

Many extra kilometres

The same conclusion was reached by Stanford University researchers late last year. The batteries of electric vehicles subject to the normal use of real-world drivers – like heavy traffic, long highway trips, short city trips, and mostly being parked – could last about a third longer than researchers have generally forecast, according to a new study by scientists working in the SLAC-Stanford Battery Centre, a joint centre between Stanford University’s Precourt Institute for Energy and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. This suggests that the owner of a typical EV may not need to replace the expensive battery pack or buy a new car for several additional years.

Almost always, battery scientists and engineers have tested the cycle lives of new battery designs in laboratories using a constant rate of discharge followed by recharging. They repeat this cycle rapidly many times to learn quickly if a new design is good or not for life expectancy, among other qualities.

This is not a good way to predict the life expectancy of EV batteries, especially for people who own EVs for everyday commuting, according to the study published on December 9 in Nature Energy. While battery prices have plummeted about 90 percent over the past 15 years, batteries still account for almost a third of the price of a new EV. So, current and future EV commuters may be happy to learn that many extra kilometres await them.

“We have not been testing EV batteries the right way,” said Simona Onori, senior author and an associate professor of energy science and engineering in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “To our surprise, real driving with frequent acceleration, braking that charges the batteries a bit, stopping to pop into a store, and letting the batteries rest for hours at a time, helps batteries last longer than we had thought based on industry standard lab tests.”

The researchers designed four types of EV discharge profiles, from the standard constant discharge to dynamic discharging based on real driving data. The research team tested 92 commercial lithium-ion batteries for more than two years across the discharge profiles.

In the end, the more realistically the profiles reflected actual driving behaviour, the higher EV life expectancy climbed. For example, the study showed a correlation between sharp, short EV accelerations and slower degradation. This was contrary to long-held assumptions of battery researchers, including this study’s team, that acceleration peaks are bad for EV batteries. (Cooldown, Stanford University)