In 2024, the Nallur Pradeshiya Sabha allocated Rs. 5 million to recon struct the Siththup paththi cemetery. A private company was contracted for the work. On February 13, 2025, during the initial construction work, four foundation pits were dug. Human skeletons were uncovered in the first and fourth pits at a depth of just half a foot

Chemmani, a quiet area near Jaffna in Northern Sri Lanka, has once again attracted national and international attention after excavations at the Chemmani-Ariyalai Siththuppaththi Hindu burial ground ordered by the Jaffna Magistrate uncovered human skeletal remains beneath the soil. The remains were initially discovered during recent construction work within the cemetery.

Chemmani, a quiet area near Jaffna in Northern Sri Lanka, has once again attracted national and international attention after excavations at the Chemmani-Ariyalai Siththuppaththi Hindu burial ground ordered by the Jaffna Magistrate uncovered human skeletal remains beneath the soil. The remains were initially discovered during recent construction work within the cemetery.

However, this discovery is not the first of its kind. The initial phase of excavation began on May 15, 2025, breaking years of silence surrounding the site. The renewed investigation stems from a chilling testimony given in 1999 by Sri Lankan Army officer Somaratna Rajapaksa. His statements prompted multiple excavations across Chemmani, which led to the recovery of approximately 15 human remains at the time.

But Chemmani’s tragic and disturbing history stretches further back to the brutal 1996 rape and murder of 18-year-old schoolgirl Krishanthi Coomaraswamy. Her death, and the subsequent disappearance of her mother, brother, and a neighbour who went in search of her, ultimately led to the unearthing of mass graves in the area. Nearly three decades later, the earth in Chemmani is speaking again revealing long-buried stories of suffering, both literal and symbolic, that have lingered in the shadows of the nation’s conscience.

Krishanthi Kumaraswamy

Prof. Raj Somadeva

On September 7, 1996, 18-year-old Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, an Advanced Level student at Chundikuli Girls’ High School in Jaffna, never returned home. After completing her examinations, Krishanthi who was on her way home had been stopped at a Sri Lanka Army checkpoint in Kaithady. When she failed to return that evening, her mother Rassammah, 16-year-old brother Pranavan, and a family friend, Kirupakaran, set out in search of her. But as we now know they too were abducted.

Their fate would only be revealed 45 days later. The mutilated bodies of Krishanthi and others who went in search of her were discovered buried in shallow graves near the army camp. Investigations revealed that Krishanthi had been raped and murdered. The heinous nature of the crime sparked national and international outrage. By July 1998, six soldiers involved were sentenced to death, while three others received lengthy prison terms.

The case has since become one of the most notorious examples of wartime impunity in Sri Lanka and critically, it was the first thread that would unravel into what is now known as the Chemmani mass grave.

Just days before her abduction, Krishanthi’s close friend and fellow Biology student, Kananadhan Sananadhi, had been killed in an accident involving a military vehicle. Deeply affected by the incident, Krishanthi reportedly confronted the soldier responsible, even grabbing him by the shirt in protest.

In the days that followed, while Sananadhi’s body remained in the morgue, it is said Krishanthi began to speak out. She had also urged fellow students to protest, condemning the incident as a serious offence committed by the military. Despite the tense atmosphere in Jaffna and the pervasive fear under heavy military presence, Krishanthi had remained brave and outspoken.

Dharmalingam Kamalakash, whose brother is believed to have been abducted by the military in 1996, believes it was Krishanthi’s courage and outspokenness that led to her murder. By demanding justice and refusing to remain silent, she likely provoked those in power, an act that may have cost her life.

Nearly 30 years later, Krishanthi Kumaraswamy’s story endures not only as a symbol of resistance and justice denied, but also as the catalyst that unearthed a deeper, darker truth buried beneath the soil of Chemmani.

Search for Selvaraja Partheepan

Karunaratnam Srikanthi, the current Secretary of the Chemmani-Ariyalai “Siththuppaththi” Hindu burial ground, has long been searching for answers about the fate of 628 missing persons from the Jaffna district. Among them is her nephew, Selvaraja Partheepan, who disappeared in 1996.

Chemmani cemetery

Partheepan was just 19 years old when he vanished on August 9, 1996. That evening, after playing with friends, he was on his way home when it is alleged he was stopped by Sri Lankan Army personnel near the Thundi Army Camp.

Desperate for answers, Partheepan’s mother had visited the camp and requested to speak to the officer in charge, identified as Captain Jawardhana. He reassured her, saying, “Don’t be afraid, we’ve only arrested him for questioning.”

But days turned into weeks. The family searched every military camp in the Jaffna area, leaving no place unexplored and no official unasked. Despite their efforts, there was no sign of Partheepan. They reported his disappearance to the Human Rights Commission, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and several politicians but progress remained elusive.

Partheepan had a brother and a sister, and fearing retaliation from the military, his mother grew too afraid to pursue legal action. Ultimately, it was his grandmother who courageously took up the search for answers.

Years later, during court proceedings, a senior Army officer, named Lalith Hewa was called to testify but he claimed to have no knowledge of Partheepan’s arrest. The legal battle drags on with no closure. Now, Partheepan’s grandmother is 94 years old, and his mother remains heartbroken, holding on to fading hope. The family has not shared much about the recent discovery of human skeletal remains at Chemmani. “When we see those bones, our eyes fill with tears,” Srikanthi said. “We wonder could one of them could be our Partheepan?”

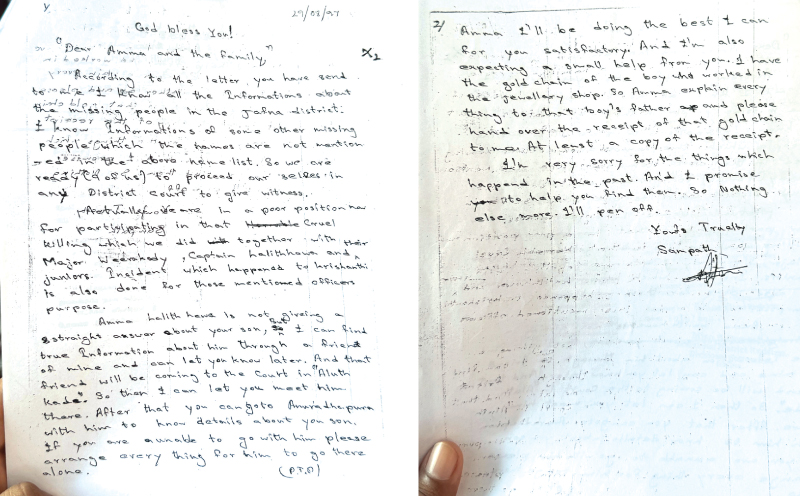

A letter from death row

For years, Partheepan’s grandmother searched not only military camps but also prisons, hoping that even a man behind bars might hold the key to her grandson’s disappearance. Driven by a singular purpose to bring her grandson home she traveled across the country.

Her journey led her to Welikada Prison in 1997, where she met Sampath, also known as Somaratna Rajapaksa, a soldier sentenced to death for the rape and murder of Krishanthi Kumaraswamy. At the time, Rajapaksa was awaiting execution. Perhaps burdened by guilt or seeking redemption, he handed her a handwritten letter, a disturbing yet revealing document that hinted at a wider network of crimes and disappearances in the North.

The letter paints a disturbing picture not just of the brutality faced by Krishanthi but of systematic disappearances and the collusion of senior military officers. It also raises questions about other officers involved.

For Partheepan’s mother and grandmother, the letter was both a flicker of hope and a gut-wrenching confirmation that the authorities may have known all along.

Uncovering the truth

Kirubakaran, a member of the cemetery’s management committee and the main litigant in the Chemmani mass grave case, was among the first to witness the chilling discovery of new human remains at the Siththuppaththi Hindu cemetery, where court-sanctioned excavations are ongoing.

“In 2024, the Nallur Pradeshiya Sabha allocated Rs. 5 million to reconstruct the Siththuppaththi cemetery. A private company was contracted for the work. On February 13, 2025, during the initial construction, four foundation pits were dug. Human skeletons were uncovered in the first and fourth pits at a depth of just half a foot,” Kirubakaran said.

Rajapaksa’s letter

He recalled the moment with visible unease. Work was immediately halted, police were notified, and a court case was filed. Official excavation began in May 2025 under judicial supervision.

But what lies beneath the soil of Chemmani is more than just human remains. While experts involved in the excavation have yet to determine the exact time period, cause of death, or other details, these findings could represent the silenced stories of hundreds of civilians who went missing during the war, many of them in 1996, a year now marked by mass disappearances in Jaffna.

“At that time, the military took away ordinary people, anyone who appeared suspicious,” Kirubakaran said. “They were taken away in the notorious ‘White Van,’ Some women were kidnapped, raped, and murdered. Others were accused of aiding the LTTE and killed without trial,” he said.

He believes that behind the killings and disappearances in Ariyalai and the surrounding areas were around 20 high-ranking military officers at the time, including Lalith Hewage, as well as seven military camps operated by the CLA.

He added that the Siththuppaththi excavation is not merely about recovering bones it is a search for justice.

Chemmani mass grave

As the excavation continues, journalists are permitted to visit the Chemmani-Ariyalai “Siththuppaththi” burial site daily at 4.30 pm, where human remains are being unearthed. The Sunday Observer team visited the site on four consecutive days to observe the activities.

On the second day, human bones were uncovered just beneath the very spot where we, the journalists, had stood and taken photographs the day before. The realisation that we had unknowingly stood above someone’s grave was deeply unsettling.

The entire excavation is under the close supervision of Jaffna Magistrate Judge A.A. Anandaraja, with the work led by archaeology expert Prof. Raj Somadeva and Legal Medical Officer Dr. Selliah Pranavan.

On the fourth day of the second phase, the excavation team uncovered something even more heartbreaking, the skeletons of several children. Among them was the fragile remains of a small child. Nearby lay a blue bag with printed letters, some clothes, and a toy. This was more than a mere discovery; it was a poignant reminder of innocent lives cut tragically short, lives never meant to end this way.

On July 2, a new excavation commenced in a different section of the cemetery, identified as suspicious by Prof. Somadeva through satellite imagery. Students from the University of Jaffna’s Archaeology Department joined the efforts to assist in the excavation.

Experts at the site said that carbon dating is unnecessary to determine the age of the remains, as these bones are distinctly different from those recently uncovered at Colombo Port and Kokkutthoduvai.

When asked about the potential number of bodies buried here, they cautioned that it is too early to estimate. They also expressed doubts whether the allotted 45-day excavation period will suffice. Despite strong suspicions, there remains insufficient concrete evidence to confirm the identities of the victims or the exact time of their burial.

As of Thursday (July 3), 34 complete human skeletons have been exhumed. Six more skeletal remains have been identified, including two suspected to belong to children.

Standing at the site each evening, watching bones being carefully unearthed, it was clear we were witnessing more than just an excavation. We were possibly bearing witness to a slow, painful unveiling of truth after decades of silence.

Justice for families

Attorney-at-Law Ranitha Gnanarajah, who is overseeing the excavation on behalf of the victims’ families, raised serious concerns about misleading content being shared online.

She said that some social media accounts have been circulating AI-generated images of human skeletons, making them appear more human-like than they actually are. According to her, these images could mislead the public and distort the purpose of the excavation. She said that those attempting to disrupt or misrepresent the process should be held legally accountable, and added that legal discussions are underway regarding the matter.

Ranitha also said that there are ongoing efforts to connect the current Chemmani excavation with the first mass grave investigation conducted in 1999. She added that former forensic expert Clifford Perera, who led the 1999 case, visited the site on July 2 and shared his insights with the current team.

Although she acknowledged that the 1999 and 2024 investigations are technically two different legal cases, she said that legal avenues are being explored to possibly combine them, following requests from families of the disappeared.

Speaking about media coverage, Ranitha said that Sinhala-language media have been slow to report on the Chemmani excavation compared to Tamil-language outlets. “Most of the journalists who come in the evenings are from Tamil media, while Sinhala media presence is minimal,” she said.

According to her the ongoing excavation at the Chemmani-Ariyalai Siththuppaththi has become more than just a search for human remains; it has reopened old wounds, revived long-standing calls for justice, and drawn renewed attention both locally and internationally.

This is the first mass grave discovered in Sri Lanka since the National People’s Power (NPP) came to power, following their historic victory in Jaffna during the last parliamentary election. Many families of the disappeared now hold a cautious but growing sense of hope that this Government might finally bring truth and justice, which previous regimes failed to deliver.

Adding further significance to the moment is the visit of the United Nations Human Rights Commissioner, Volker Türk’s visits to Chemmani last week. Families and rights groups believe this visit also increased international scrutiny and pressure on the authorities to ensure transparency and accountability in the investigation. For many families, this may be the first time in decades that they feel their pain is not being ignored, but heard, investigated, and potentially answered.