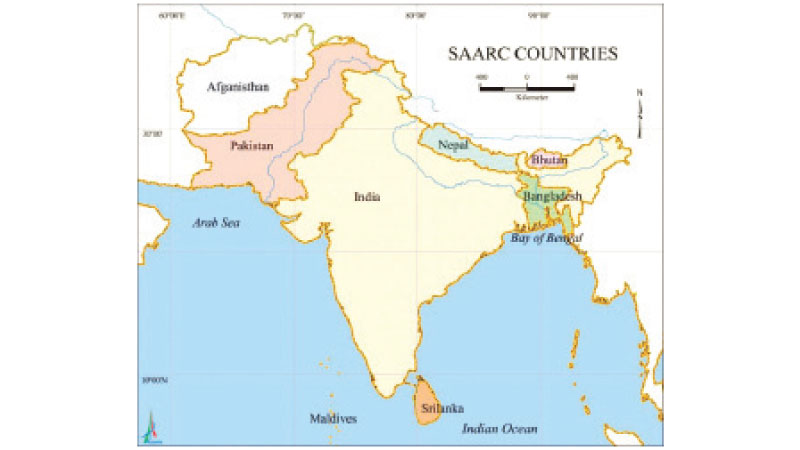

The ongoing China-India contestation for supremacy in South Asia is poised to escalate, particularly as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China advance plans for a new regional organisation that could supplant the moribund South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).

Yet, the deeper malaise afflicting South Asia transcends mere power struggles between giants; it is the entrenched fragmentation of a region that, paradoxically, shares millennia of intertwined history, culture, and economic interdependence.

This fragmentation is starkly illustrated by the paltry intra-regional trade, which hovers below seven percent—an anachronistic statistic in an era defined by economic blocs and transnational cooperation. The smaller South Asian States, whose strategic partnerships are sporadic and underdeveloped, remain ensnared in the gravitational field of India’s hegemonic posture, often reduced to pawns in New Delhi’s economic subjugation and political monopoly. Unlike ASEAN’s relative cohesion or Israel’s diplomatic breakthroughs epitomised by the Abraham Accords, South Asia languishes in disunity—a condition no doubt exacerbated by the legacy of the Partition and a colonial blueprint deliberately designed to fracture.

The fissures that afflict the subcontinent today are not merely incidental; they are the predictable by-products of a colonial architecture crafted for divide and rule. The British Raj’s demarcations—disregarding ethno-religious continuities and economic affinities—culminated in the violent and traumatic Partition of 1947. This cataclysmic event irreparably severed a shared polity into mutually antagonistic nation-States, embedding a cycle of mistrust and enmity that has since ossified into the region’s political DNA. As the eminent historian Ayesha Jalal elucidates, “Partition was not simply a political division but a social cataclysm that ensured that South Asia would inherit a legacy of perpetual hostility.” The resultant statecraft—preoccupied with existential threats and zero-sum calculations—has obstructed any earnest attempt at regional cohesion.

Lack of integration

The conspicuous absence of tangible integration mechanisms in South Asia contrasts sharply with other regional successes. ASEAN, despite its heterogeneity, has cultivated a functional community underpinned by economic collaboration and conflict mitigation, aided by a shared vision and diplomatic fortitude. The Abraham Accords, meanwhile, demonstrate how historically intractable conflicts can yield to strategic pragmatism and external facilitation.

South Asia’s failure to emulate these models is a glaring indictment of its political leadership’s unwillingness or inability to rise above entrenched grievances, sectarianism, and narrow nationalism. The region’s fractiousness is not an organic inevitability but a cultivated condition—one sustained by external actors whose geopolitical designs have consistently benefitted from South Asia’s disunion.

From colonial subjugation through the Cold War and into the present-day geopolitical order, Western powers have systematically instrumentalised South Asia’s divisions to secure their strategic interests. Whether through the partitioning of India, the militarisation of the India-Pakistan rivalry, or the contemporary alignment of South Asian States within competing global power frameworks, Western policies have perpetually fomented discord.

The Quad, for example, while ostensibly a security architecture to counterbalance China, has further entrenched fault lines, compelling regional States to navigate a precarious geopolitical balancing act. Consequently, South Asia’s leaders, constrained by domestic pressures and regional rivalries, have repeatedly failed to adopt bold initiatives that could recalibrate the regional order towards cooperation and mutual prosperity.

Within this complex matrix, SAARC’s institutional impotence is emblematic of South Asia’s broader predicament. Conceived as a vehicle for regional integration, it has been paralysed by the persistent India-Pakistan antagonism and India’s hegemonic tendencies vis-à-vis smaller neighbours. The smaller States, rather than coalescing into a cohesive bloc, remain fragmented and often co-opted into New Delhi’s orbit, limiting their agency and constraining their strategic autonomy.

India’s utilisation of economic instruments—such as restrictive tariffs and border closures—to exert pressure on Pakistan and influence the political alignments of smaller neighbours reflects a persistent dynamic of domination and subjugation. This hegemonic posture erodes trust and suppresses the emergence of authentic, mutually beneficial regional cooperation.

The collapse of SAARC, crystallised by India’s boycott of the 2016 summit in Pakistan following the Uri terror attack, demonstrates the relentless cycle of paralysis that has rendered South Asia a geopolitical wasteland. This rupture was no mere diplomatic impasse but a retreat into hostility, igniting a series of retaliatory measures—crippling trade embargoes, halted connectivity initiatives, and the unravelling of fragile regional ties that once hinted at economic revival. The 2025 Pahalgam attack only intensified this entrenched enmity, with both nations cynically exploiting the tragedy to amplify discord rather than seeking dialogue or diplomatic solutions.

Self-imposed stalemate

Instead, India and Pakistan shamelessly turned to the West, the very architects of South Asia’s fragmentation, to mediate conflicts they themselves perpetuate. These external powers have long manipulated regional divisions, fostering terror and endemic poverty as levers of influence. The two nuclear-armed neighbours isolate themselves behind closed borders and severed waterways, extinguishing centuries-old channels of trade and cultural exchange. This self-imposed stalemate condemns millions to a future of strife and underdevelopment, while squandering the immense potential that regional cooperation might unlock.

The tragic reality is that the myopic political theatre which ensued failed to address the root causes of instability in the region. Both India and Pakistan appear ensnared in a self-reinforcing cycle where every act of aggression justifies counter-aggression, and diplomatic overtures are frequently eclipsed by nationalist fervour and political expediency. In the meantime, the smaller South Asian countries have been relegated to the periphery of regional strategy, their development and security concerns subordinated to the interests of the dominant powers. Afghanistan’s inclusion in SAARC, for instance, has done little to mitigate its protracted conflict and humanitarian crisis, which continue to impact regional stability.

The South Asian predicament calls for more than the perpetuation of hegemonic postures or the substitution of one regional organisation for another. It demands an unflinching reckoning with history and a courageous commitment to transformative cooperation. This includes not only confidence-building between India and Pakistan but the empowerment of smaller States to assert their interests free from hegemonic encumbrances. It requires leadership that prioritises shared challenges—climate change, poverty alleviation, human trafficking, and economic development—over parochial rivalries. Most critically, it calls for disentangling South Asia from the geopolitical machinations of external powers that benefit from regional instability.

South Asia’s potential as a cohesive economic and geopolitical unit remains tantalisingly out of reach, stymied by a colonial legacy, historical trauma, hegemonic rivalries, and external interference. Without a fundamental transformation of its regional paradigm, South Asia will continue to languish as an exemplar of what divides rather than unites. To reverse this trajectory is not merely desirable but imperative for the prosperity and security of over a billion souls whose destinies are inextricably linked.