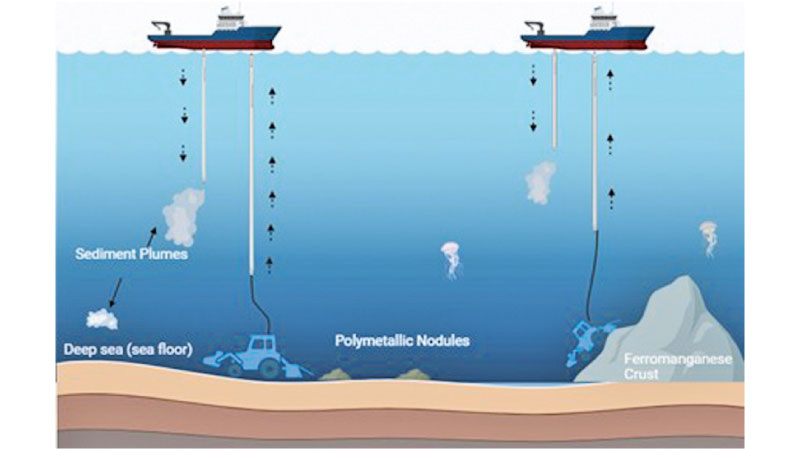

Beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean, in some of the deepest parts of the seabed, lies a treasure trove of minerals with metals, such as nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese. These metals are essential for the batteries that power electric vehicles and the broader green energy transition.

These potato-sized polymetallic nodules have sparked interest among scientists, entrepreneurs, and Governments looking for cleaner alternatives to traditional land-based mining. However, a new study led by a Sri Lankan research team sheds critical light on the risks that could halt this emerging industry before it even begins.

These potato-sized polymetallic nodules have sparked interest among scientists, entrepreneurs, and Governments looking for cleaner alternatives to traditional land-based mining. However, a new study led by a Sri Lankan research team sheds critical light on the risks that could halt this emerging industry before it even begins.

In a rare cross-border collaboration, researchers, including Ms. Thisuri Fernando, Ms. Poorni Ranaweera, Ms. Tirishe Droohithya, Dr. Gayithri Kuruppu and Dr. Sandun Dassanayake from the University of Moratuwa, Dr. Nimila Dushyantha from Uva Wellassa University, and Associate Prof. Saman Ilankoon from Monash University Malaysia Campus, have delivered a structured evaluation of the most pressing challenges facing Deep-Sea Mining (DSM). The team applied an advanced decision-making tool known as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to rank six key risk categories, from technological uncertainties to shifting regulatory landscapes.

The clock is ticking on critical mineral supply

The study comes at a crucial moment in the global debate over DSM. As the demand for battery metals is expected to triple by 2035, industries are seeking alternative sources beyond conventional mines in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia. Yet, DSM remains controversial. Environmentalists warn that disturbing seabed ecosystems, many of which remain undiscovered, could have irreversible effects on marine biodiversity. Policymakers, meanwhile, remain divided.

The United Nations’ International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees mining in international waters, has yet to finalise regulations for commercial exploitation, prompting calls from various countries and advocacy groups for a moratorium. In the face of this uncertainty, the Sri Lankan-led team is motivated to quantify and compare the broad and often subjective threats that DSM ventures must contend with.

According to the team, “Investors kept telling us they had no structured way to weigh the jumble of technical, social, and market threats. We wanted to put numbers on those grey zones so governments and financiers can argue from common ground.” To achieve this, the researchers employed the Delphi method, a multi-round expert polling technique, to refine risk categories by incorporating inputs from professionals in marine science, finance, mining, and environmental governance.

After identifying the six most relevant risk types (Risk of Continuity, Market Price Volatility, Technological Risk, Social Risk, Legal Risk, Finance and Return Risk), they asked experts to compare each pair of risks, eventually running their judgments through the AHP model. The result was a weighted ranking of the hazards that could make or break a DSM project.

Risk of continuity

The most significant finding is that the team identified “risk of continuity” as the most critical threat to the industry. This category includes policy ambiguity, weak legal enforcement, environmental opposition, and cost overruns that can halt operations midstream. In other words, DSM’s most significant risk is not technology failure or metal price crashes; it’s the lack of stable, science-driven governance and the social licence to operate. Closely following this was the volatility of metal markets.

Prices for key minerals, such as nickel and cobalt, have fluctuated dramatically over the past decade, driven by global politics, speculative bubbles, and shifting technology trends. These wild fluctuations can severely impact project viability, especially given the massive capital expenditure required for DSM infrastructure.

While the third-ranked concern, technological risk, is often viewed as the most obvious barrier, the study found that recent advancements, notably Japan’s successful pilot of seabed extraction, have started to build confidence in deep-sea mining systems. Still, concerns persist over the reliability of robotic harvesters, deep-sea pumps, and the ability to repair equipment in extreme conditions.

Financial risk isn’t the biggest barrier

Interestingly, social and legal risks were significant but less dominant than expected. While public backlash and legal challenges remain obstacles, the researchers argue that these can often be managed through early stakeholder engagement and benefit-sharing models. The lowest-ranked risk category was financial return, which may be surprising, given the high costs and long timelines typically associated with DSM ventures.

However, the team notes that financiers appear more willing to tolerate long payback periods if other risks, particularly those related to governance and regulatory clarity, are well-managed. This shift in perspective is central to what the authors refer to as “intelligent finance.”

Rather than labelling DSM as inherently too risky, they propose tailored financial structures that spread risk across multiple stakeholders, including insurers, green-bond investors, equipment manufacturers, and host Governments. According to the team, “We need to move beyond the traditional project finance lens. Think ESG-focused capital, risk-sharing consortia, and real-time environmental monitoring embedded into contracts. That’s the only way DSM can be both viable and responsible.”

The study also emphasised that sustainability-linked credit lines could be designed to reward companies that meet environmental benchmarks such as minimal sediment disturbance or biodiversity conservation. Drawing parallels with green bonds for rainforest protection, the team believes similar models can be applied to ocean environments.

Sri Lanka’s role in the global blue economy

Sri Lanka may not have immediate ambitions in DSM, but the country is interested in the blue economy. With its long coastline, strategic location in the Indian Ocean, and experience in mineral extraction from graphite to ilmenite sands, Sri Lanka can play a meaningful role in shaping the regional discourse on responsible resource use. Moreover, this study demonstrates the intellectual capacity of Sri Lankan institutions to influence global resource governance through evidence-based frameworks.

From risk mapping to responsible mining

What makes this research especially timely is its balanced tone. It does not promote DSM unconditionally, nor does it reject it outright. Instead, it provides a practical, data-driven approach to evaluating which risks matter most and how they can be managed. As debates intensify over whether to allow seabed mining to proceed, such clarity is invaluable.

Ultimately, this Sri Lankan-led collaboration provides a blueprint for countries, companies, and communities navigating the promises and perils of deep-sea extraction. With mounting demand for critical minerals and increasing scrutiny on how they are sourced, having a reliable framework to assess risk is not just academic, it’s essential. As the team put it, “The future of DSM will depend not just on what’s under the sea, but on how wisely we decide to go after it.”